What does a UX designer actually produce? Here, we will explore the concept of UX deliverables, a term that describes the outputs of a UX design process during its various stages. The deliverables produced by UX designers vary according to their role in the design team and also depending on the methods and tools used by each role. We will provide an overview here of some of the most common types of deliverables.

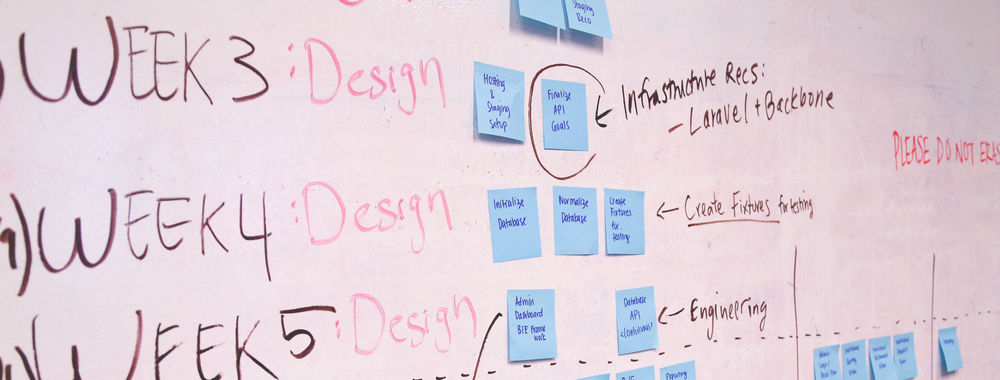

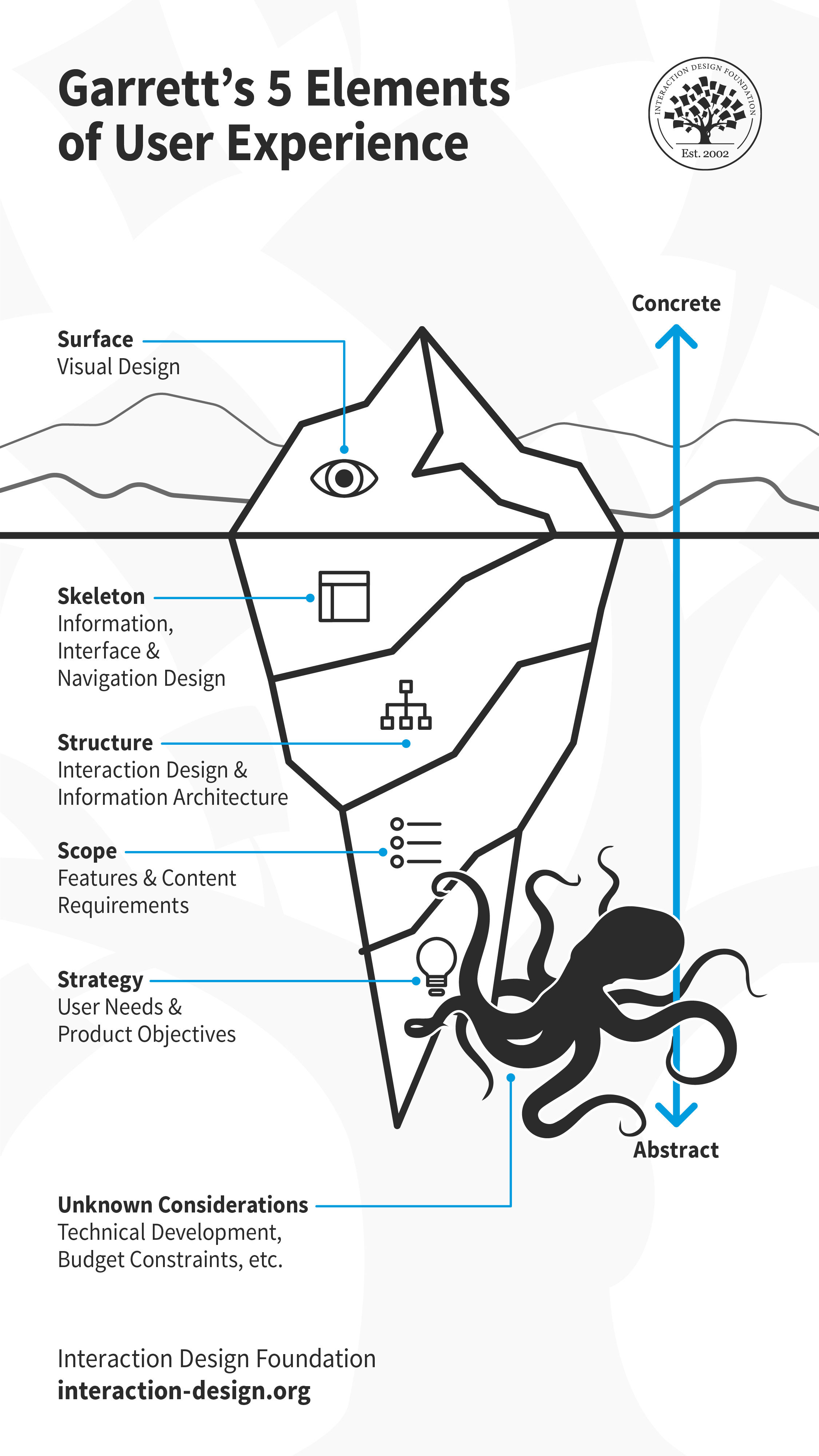

When you join a UX team, you might find yourself on unfamiliar grounds. Every team has its preferred (or defined) tools, methods and processes. While there is no single, gold-standard UX design process, most teams’ process follows closely with Jesse James Garrett’s 5 elements of user experience. Building up from the most abstract, Strategy, to the most concrete, Surface, each element has a few associated activities. Let’s look at each of these closely, and a few common deliverables associated with them.

Much like an iceberg, visual design is only the surface of user experience. Underneath, there is so much more including skeleton, structure, scope and strategy. These layers are by no means standalone, and influence each other. Decisions taken at one plane can cascade up or down the layers. There will likely be other considerations that emerge later, which might impact the experience. For example, if the team encounters technical challenges or budgetary constraints during development, they might have to revisit some design decisions.

Tip: Detach Yourself from Your Deliverables

As a UX designer, you will find yourself working on different types of projects, each demanding a unique approach. While you must familiarize yourself with as many tools and methods as possible, in practice, you will likely use only some of them regularly, and others for exceptional cases. No matter which design activity you conduct, remember to detach yourself from the deliverables.

Design is a fluid activity, and you must mentally prepare yourself to adapt to changes — internal, external, known and unknown. For example, you will often find yourself revising your designs after a usability test. This could be at the surface, skeleton or even strategy level. Sometimes your research might reveal new insights that prompt you to reconsider the product’s core value (strategy). Perhaps the technical team runs into a roadblock that makes it difficult to implement your solution (scope). In all these, and many other cases, you (and your team) will need to adapt your design decisions.

As designers — as humans — we tend to get attached to our work and find it hard to change course. The beauty of (and indeed the toughest challenge in) design is to be open to iteration. Always remember, iteration is a crucial part of a UX designer's work, and you will rarely ever create a “final” deliverable in the first attempt.

User Needs and Product Objectives

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

— Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein's words are true for any new project that you begin, and especially so for UX design. When you join a UX team, you might work on a new product, building it from the ground up. Or, you might join at a time when the product is already built and launched and the team is looking to enhance it incrementally. No matter which stage or shape the product or service is in, you will need to dig in and understand the product objectives and user needs before you begin your work. By building (and reading) personas, storyboards and customer journey maps, you can get a better understanding about why you are designing, and for whom.

1. Personas

Illustration depicting a user persona.

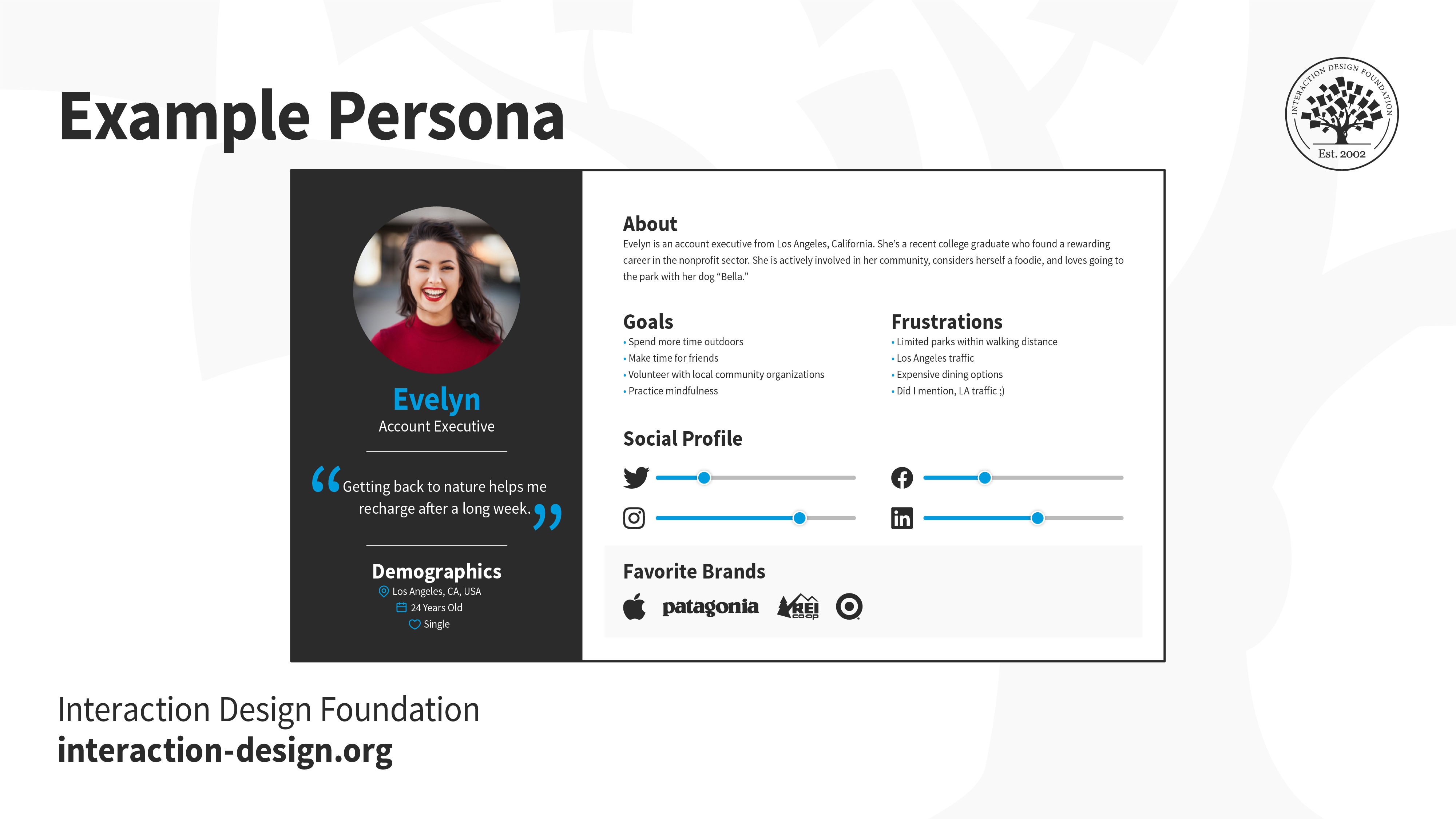

A persona is a fictional character which the designers build as a sort of user stereotype. It represents the typical users, their goals, motivations, frustrations and skills. Other information such as demographics and education backgrounds complete the persona. Depending on the scope of the projects, designers will generate a number of different personas to capture as wide a part of the audience as possible. Generating personas helps designers empathize with the users and demonstrate a thorough understanding of who they are and what they want to achieve.

Example of a user persona. Demographics, skills, goals and frustrations are represented visually or in text.

2. Storyboards

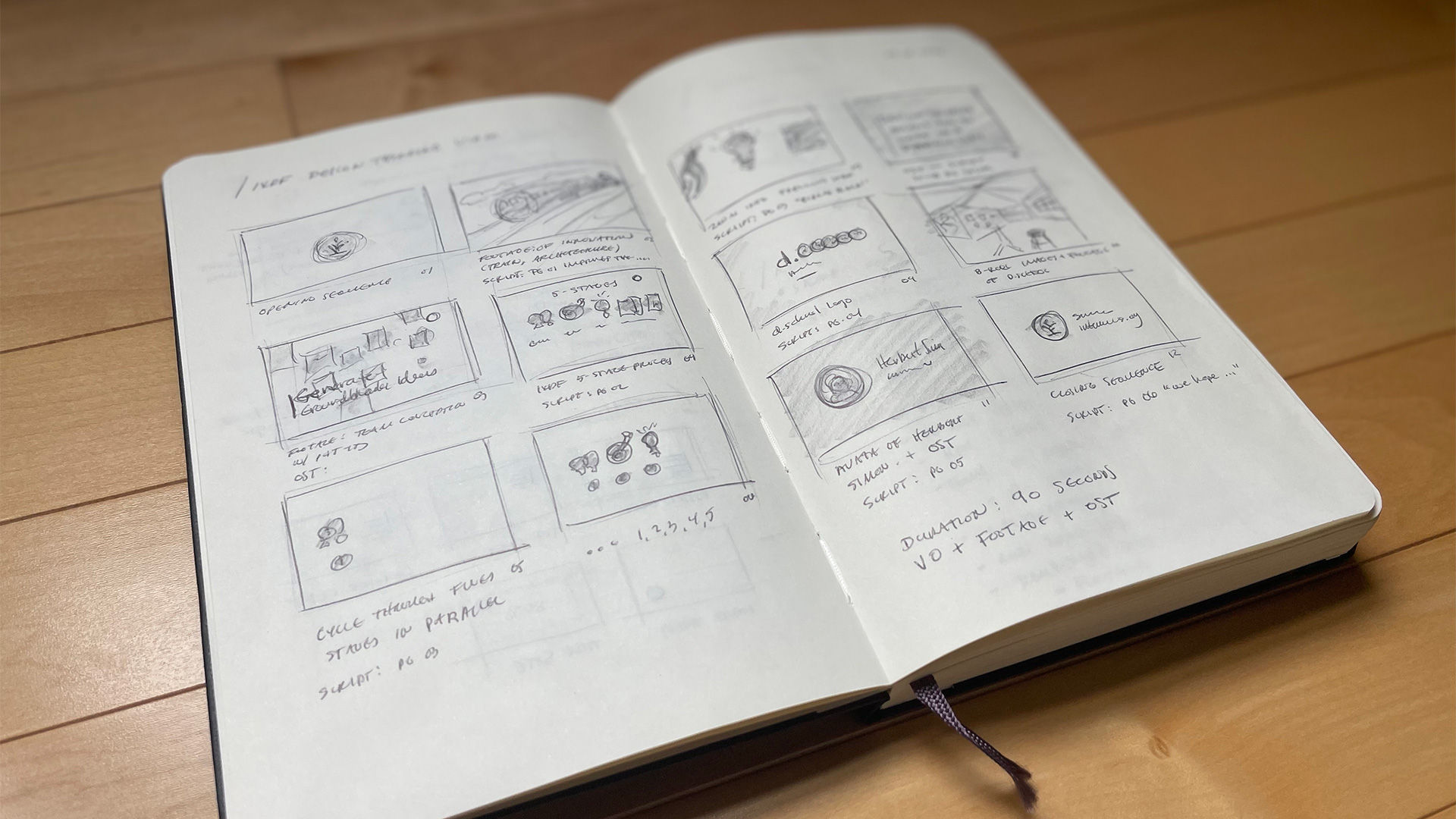

Illustration depicting storyboards.

A storyboard is an idea borrowed from the movie industry. It essentially consists of a comic strip, outlining the user’s actions and circumstances under which these are performed. The power of this idea is that it doesn’t only demonstrate what the user does, but it also reveals the environment, which might be affecting how or why the user does something.

A storyboard helps visualize the users’ actions and also the environment in which they take place. While mostly used for empathizing with the users, storyboards can also be used to help illustrate alternatives in interaction design.

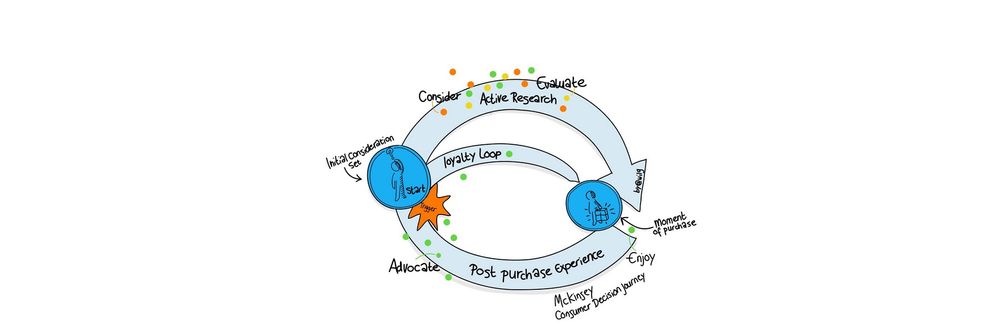

3. Customer Journey Maps

Illustration depicting a customer journey map.

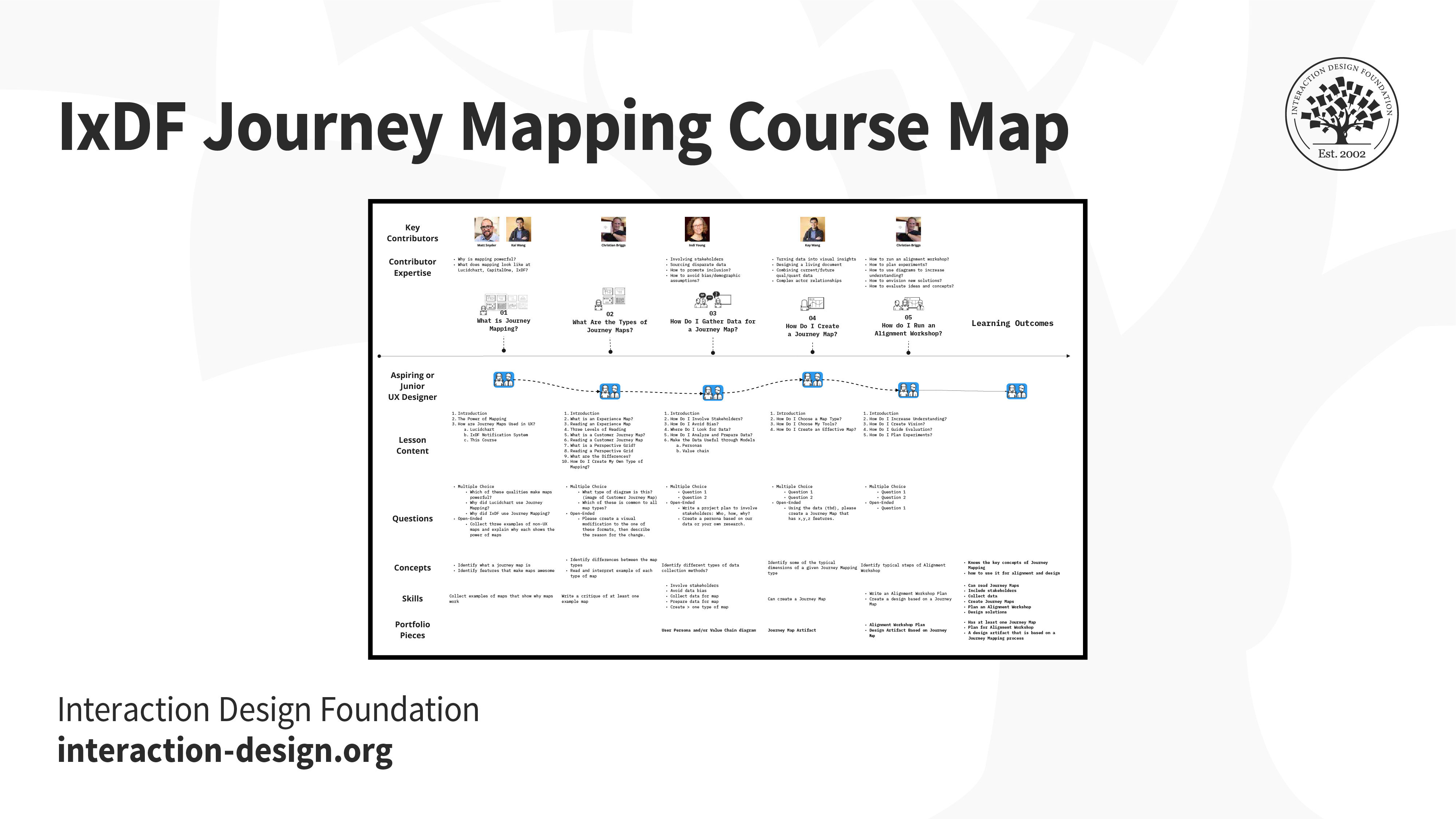

A customer journey map is a diagram that represents the steps (i.e., the process) taken by a user to meet a specific goal. By laying the process out along a timeline, designers can understand the changes in the user’s context, and their motivations, problems and needs along the way. By identifying the major stumbling blocks for users, the designers can better relate to their problems and begin to see where a product or service might fit along the way to help the user.

Customer journey map of a student's course experience.

Features and Content Requirements

As a new UX designer, you might be asked to design certain features or work around pre-defined requirements. As a more experienced designer, depending on the team you join, and your role, you might be involved in conversations about what those features and requirements might be. In each of these cases, you will likely participate in brainstorming sessions: to generate ideas for new features, or for implementing those features.

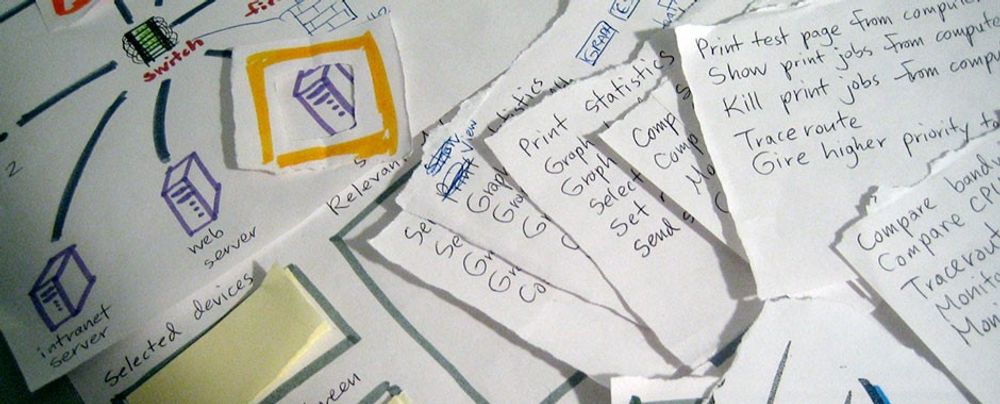

4. Brainstorming

Illustration depicting brainstorming.

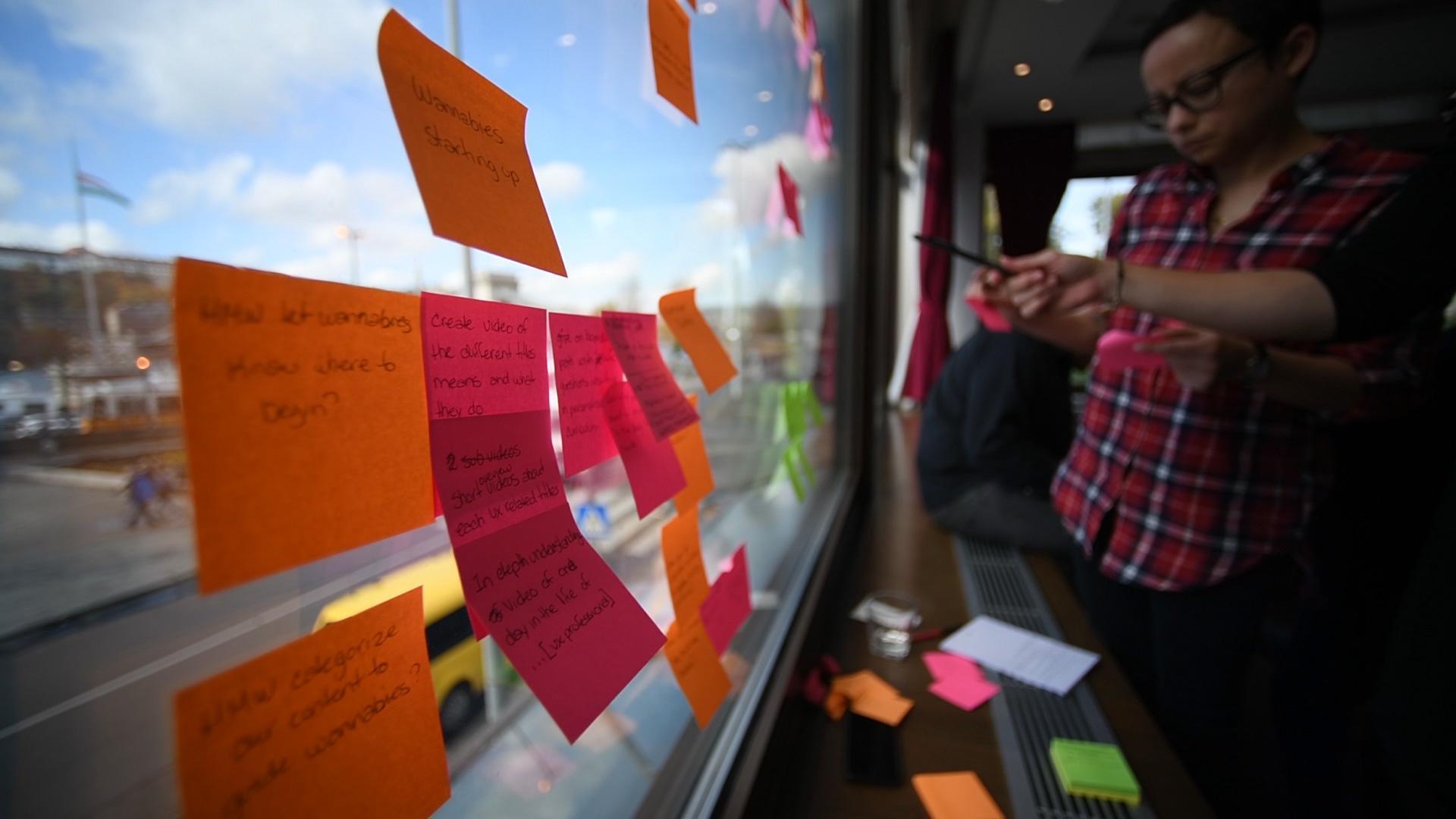

Brainstorming is a process whereby a team of designers generates ideas about how to address the issues and opportunities identified in the user research phase. The concept here hinges on the generation of as many ideas as possible (even if they are completely wild) so that the designers can later sift through these and reduce them to the ideas that seem most promising. A central point is that the team members are free to explore all angles and realms; indeed, the best solutions can sometimes sprout from the craziest-sounding notions.

Sticky notes are incredibly useful in brainstorming sessions. Designers write down all of their ideas — one idea per sticky note. Sticky notes enable the team to move ideas around, grouping ideas into themes in real time while discussing them. Having all the ideas sorted and visually laid out in one space makes it much easier for the team to narrow down, and ultimately pick the best idea to develop further.

5. Content Strategy

Illustration depicting content strategy.

“Content strategy plans for the creation, publication, and governance of useful, usable content. Content strategy plans for valuable, findable, meaningful content.”

— Kristina Halvorson, author of Content Strategy for the Web

Content strategy is the practice and process of ensuring that content is written, published, edited, repurposed and archived at the right time, and for the appropriate audience.

Content strategy is extremely important if you’re working on a product that is content-heavy, such as an online magazine. It is also relevant for non-publication-oriented products. In a fiercely competitive market, digital marketers often rely on content to increase traffic (that’s marketing-speak for potential users). Your users will likely see marketing communication and content before interacting with your product, thus setting expectations. As a UX designer, you may not be directly involved in creating a content strategy, but you must work closely with the person (or team) who works on it, to ensure the communication matches your design.

Information Architecture and Interaction Design

The information architecture is analogous to the blueprint of a house. Larger UX teams might have specialist information architects and interaction designers, while in smaller teams, UX designers will likely perform these roles.

Designers often use different types of flowcharts to visualize the information and interactions, such as sitemaps and user flows.

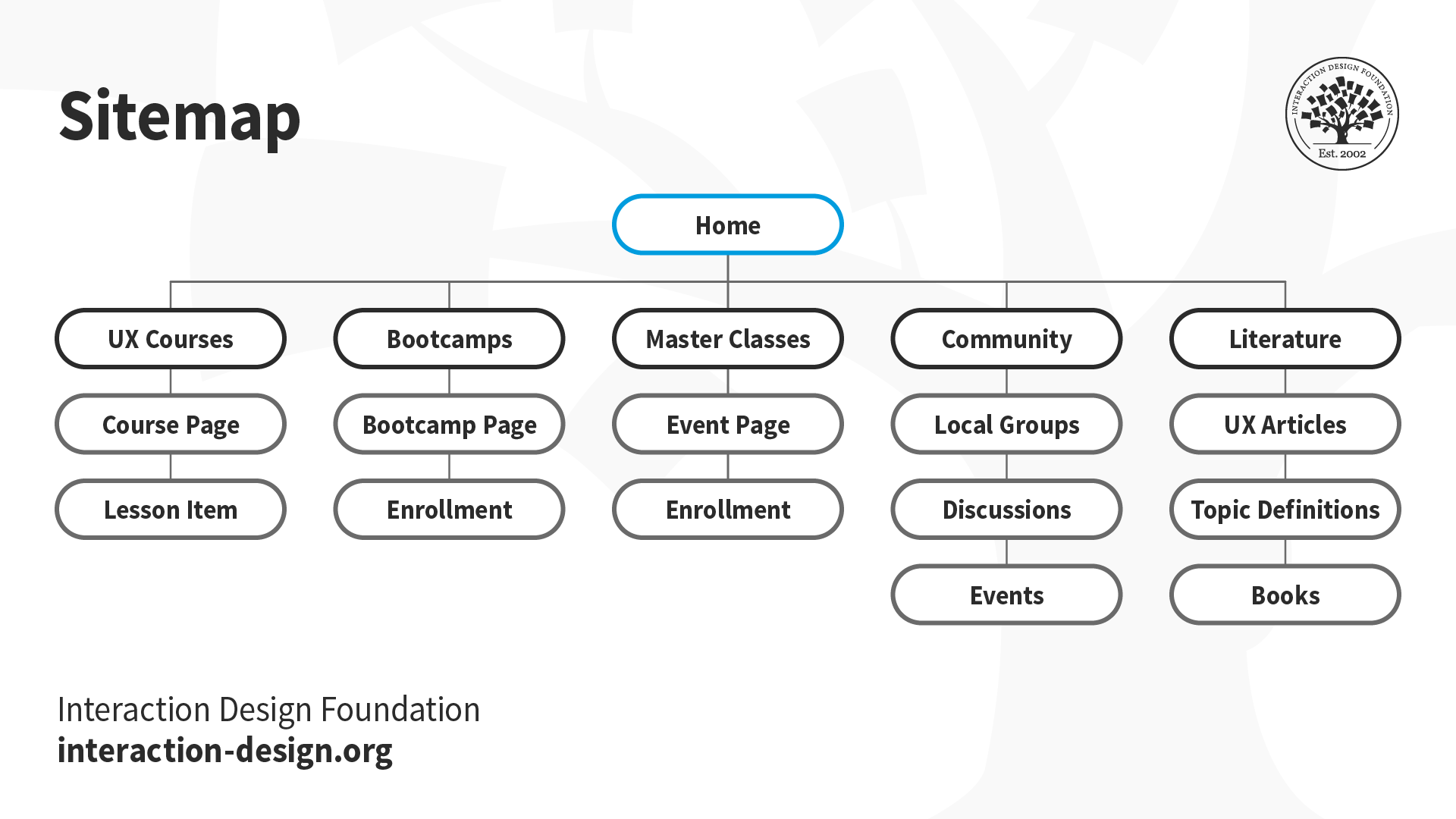

6. Sitemaps

Illustration depicting a sitemap.

You might have come across sitemaps while browsing different sites. Like physical maps, they help you find your way through a website. UX designers often create similar sitemaps to show the hierarchy and navigation structure of a website or an application. Such maps are often produced for mobile apps as well. They show how the content will be organized into logical “screens” or sections, and how the user may transition from one section of your service to another.

An example sitemap which shows how content on a website is organized and how a user can navigate each section.

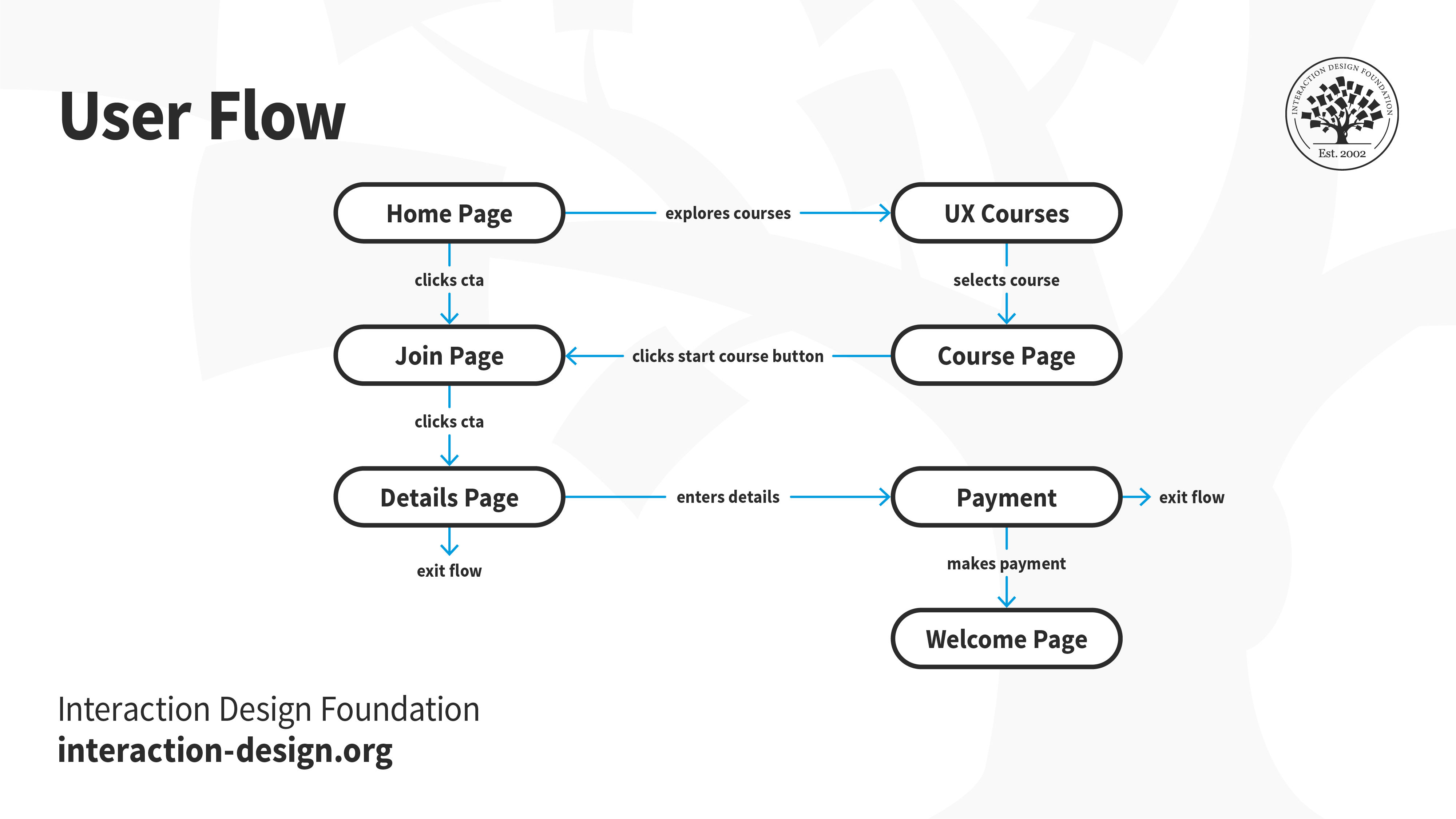

7. User Flows

Illustration depicting a user flow.

A user flow (also known as a task flow) diagram is a simple chart outlining the steps that a user has to take with your product or service in order to meet a goal. In contrast to the customer journey map, the user flow diagram considers only what happens with your product (that is to say, ignoring all external factors). These diagrams can help designers quickly evaluate the efficiency of the process needed to achieve a user goal and can help pinpoint the “how” (i.e., execution) of the great ideas identified through brainstorming.

An example user flow showing the user’s actions within an application.

Interface Design

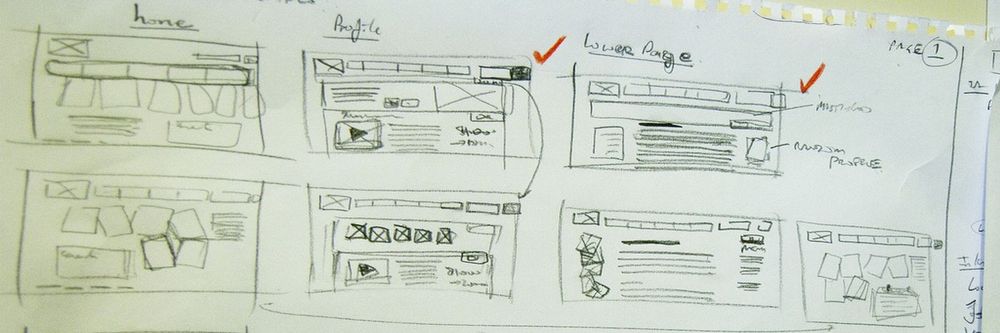

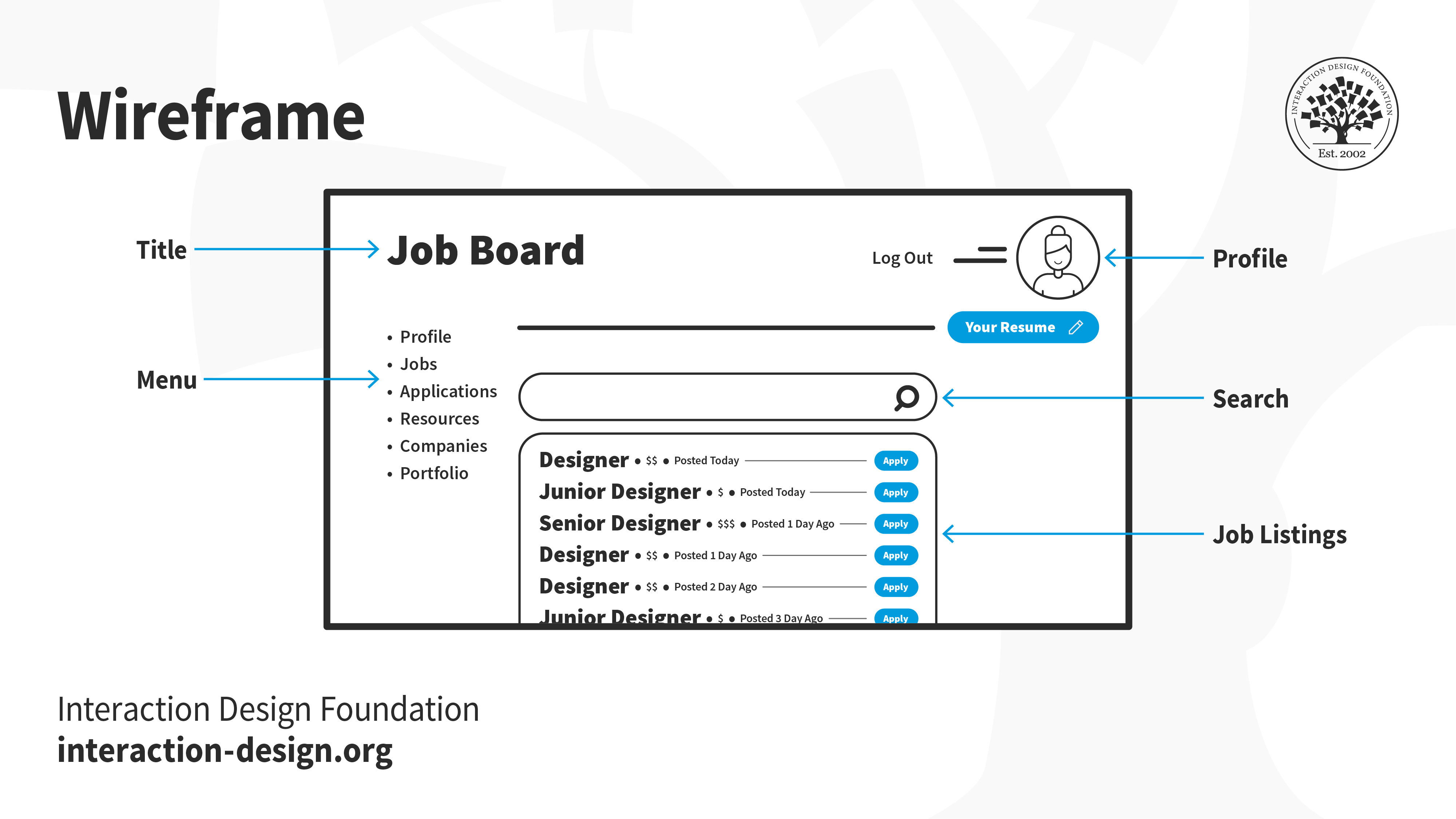

8. Wireframes

Illustration depicting wireframes.

Just as a sculptor creates a wireframe before slapping on clay to craft a statue, an interface designer too creates a wireframe before adding in the details. Wireframes are the first interface-related deliverables in the UX design process and are just a step away from the surface layer and visual design. They are the first tangible elements of the proposed ideas or solutions.

An example wireframe which brings together structure, navigation, information architecture, layout details, and more. Designers rely on hand-drawn sketches, sitemaps and user flows to create a wireframe. They can be an intermediary step between sketches and prototypes.

Good wireframing is the skill of creating lean layouts so your team and stakeholders can quickly determine if concepts are worth developing. They are typically grayscale and do not include visual or branding elements.

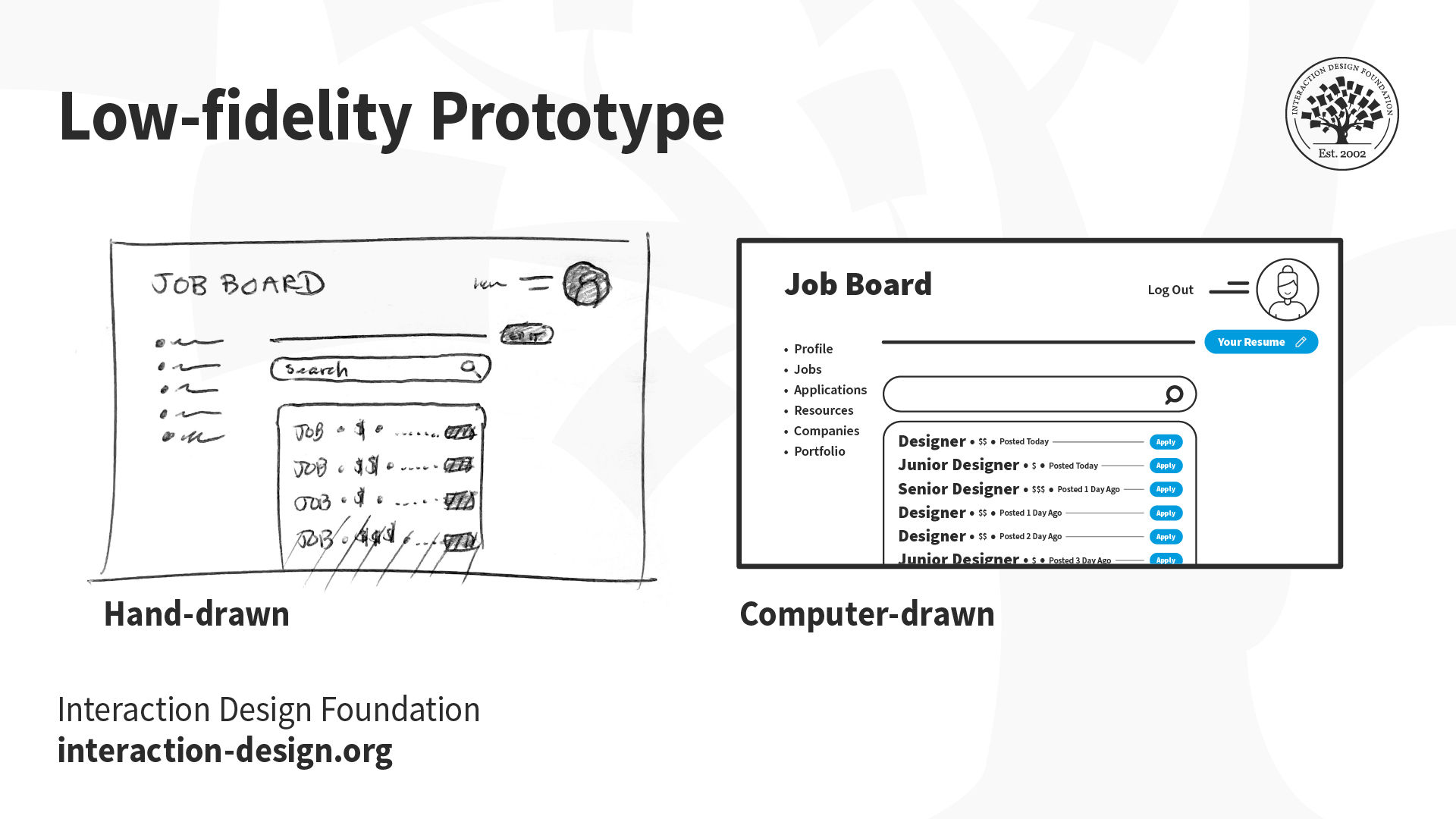

9. Prototypes

Illustration depicting a low-fidelity prototype.

A prototype is a simulation of the product or solution you want to build. It is an early version of a product or feature with which people can interact. Prototypes allow you to bring your idea closer to life before investing time and energy in building the real thing. You can test your idea with real people to identify friction points and iterate on your design — without having to write a single line of code. Common types of prototypes include low-fidelity and high-fidelity.

Low-fidelity prototypes

A low-fidelity prototype omits any visual design details and serves as a rough guide to allow designers to get a feel of how and where they should place content. Low-fidelity prototypes can start as hand-drawn sketches (which are great, because they are fast and cheap to produce, so you can easily throw them away if you change your mind) and later refined as computer-drawn wireframes, which are more faithful to the presentation of information on a real screen, but still lacking visual design details.

Examples of hand-drawn (left) and computer-drawn (right) low-fidelity prototypes.

High-fidelity prototypes

A high-fidelity prototype is a step up from a low-fidelity prototype. They are often called pixel-perfect prototypes because they try to show all the visual and typographic design details of a product, as it would be shown on a real screen. They take into consideration physical screen dimensions and are produced in a size that corresponds to the physical device’s size. Although these require a lot more time to produce compared with low-fidelity prototypes, they are often the type of illustration that you would want to show to a customer or stakeholder.

An example of a design and high-fidelity prototype for desktop.

Information Design

The information that you present on an interface plays a significant role in guiding the user and helping them accomplish their goals. Information can refer to text, as well as audio-visual elements, such as animated gifs, explainer videos and voice-overs.

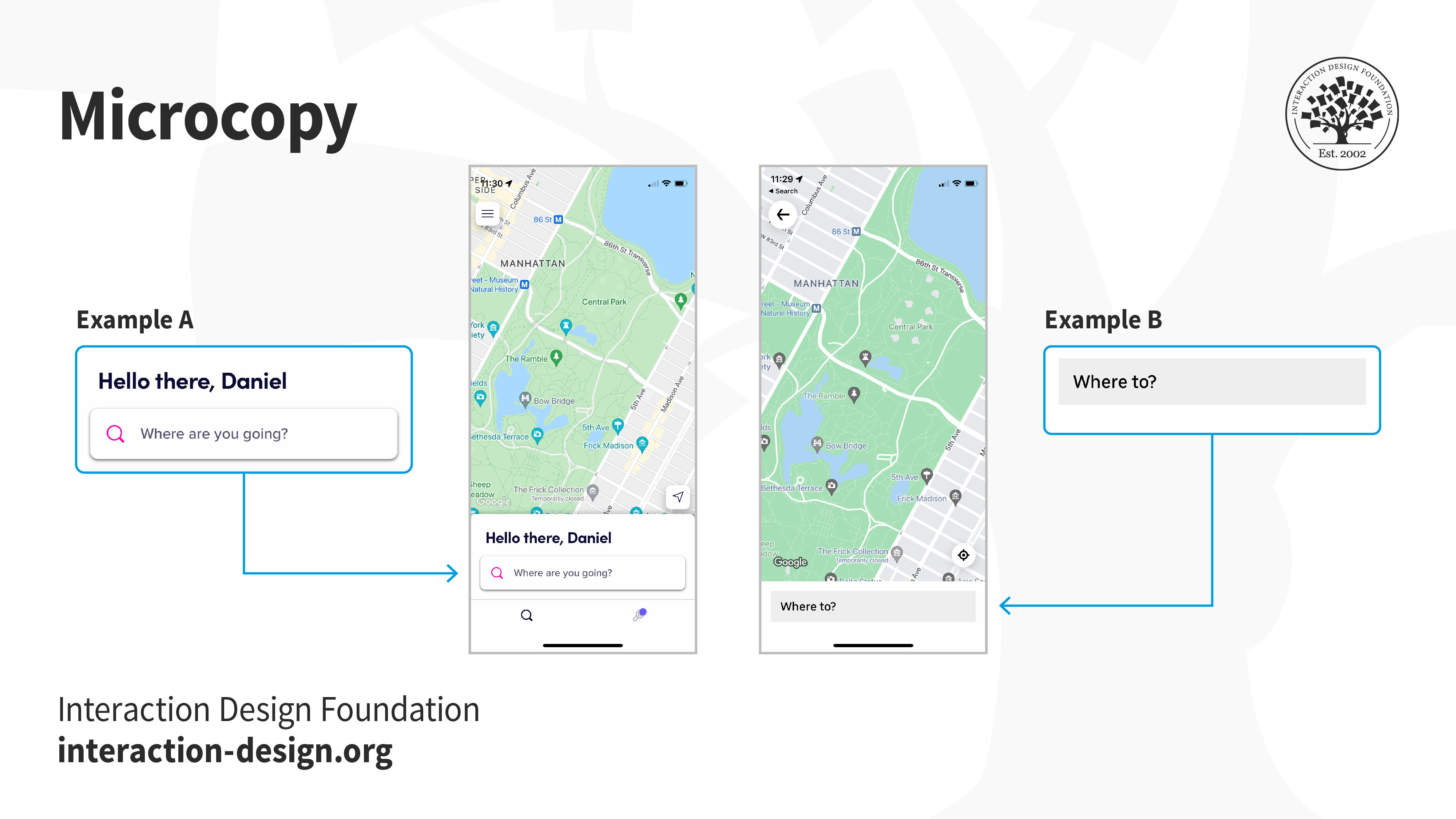

10. UX Writing / Microcopy

Illustration depicting information design.

UX writing is the practice of choosing the words people see when they interact with software, an app, or a website. This specialized writing is about designing the conversation between a digital product and the person using it. From the heading text on each screen and button labels to the navigation menu items and error messages, all the text on the interface of an application falls under the term microcopy or UX writing.

Whenever you use an app or a website, you encounter microcopy. It may not have been done by a UX writer, but those word cues are important for a positive user experience. True to its name, when the microcopy is doing its job well, you don’t even notice it — just like good UX!

Rideshare apps Lyft (example A) and Uber (example B) allow users to choose their destination to book a ride. In this case, the user is greeted with a message — microcopy — on the primary page. Notice the difference between the messages on both applications. As a user, which one would you prefer?

In large software companies and digital agencies, you might have help from dedicated UX writers. UX writing is sometimes bundled into the work of content strategists. In most cases, however, UX writing is part of a UX designer’s role.

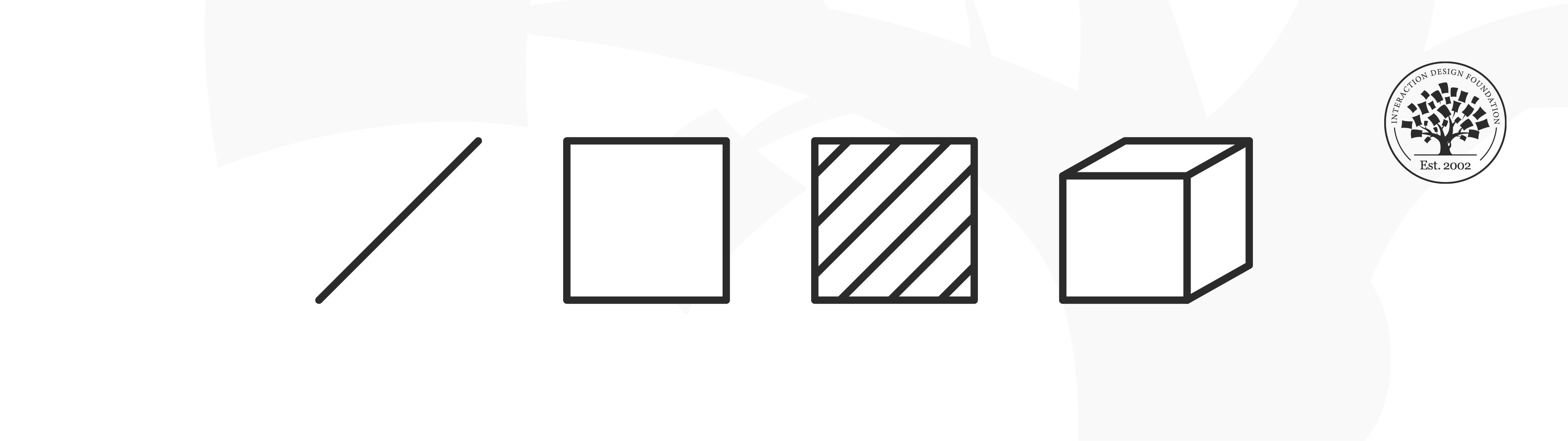

Visual Design

Illustration depicting visual design elements.

“Problems with visual design can turn users off so quickly that they never discover all the smart choices you made with navigation or interaction design.”

— Jesse James Garrett, UX Designer & Co-founder of Adaptive Path

Users form their first impressions typically in 50 milliseconds. The surface of the product (often the visual design) is one of the first elements that users of your product or service will see. It is, however, often the last detail added to a product. This is because the visuals (and sounds) depend on all the decisions taken beneath the surface. Any changes to the layout, navigation, copy, etc. have a cascading effect on the surface layer.

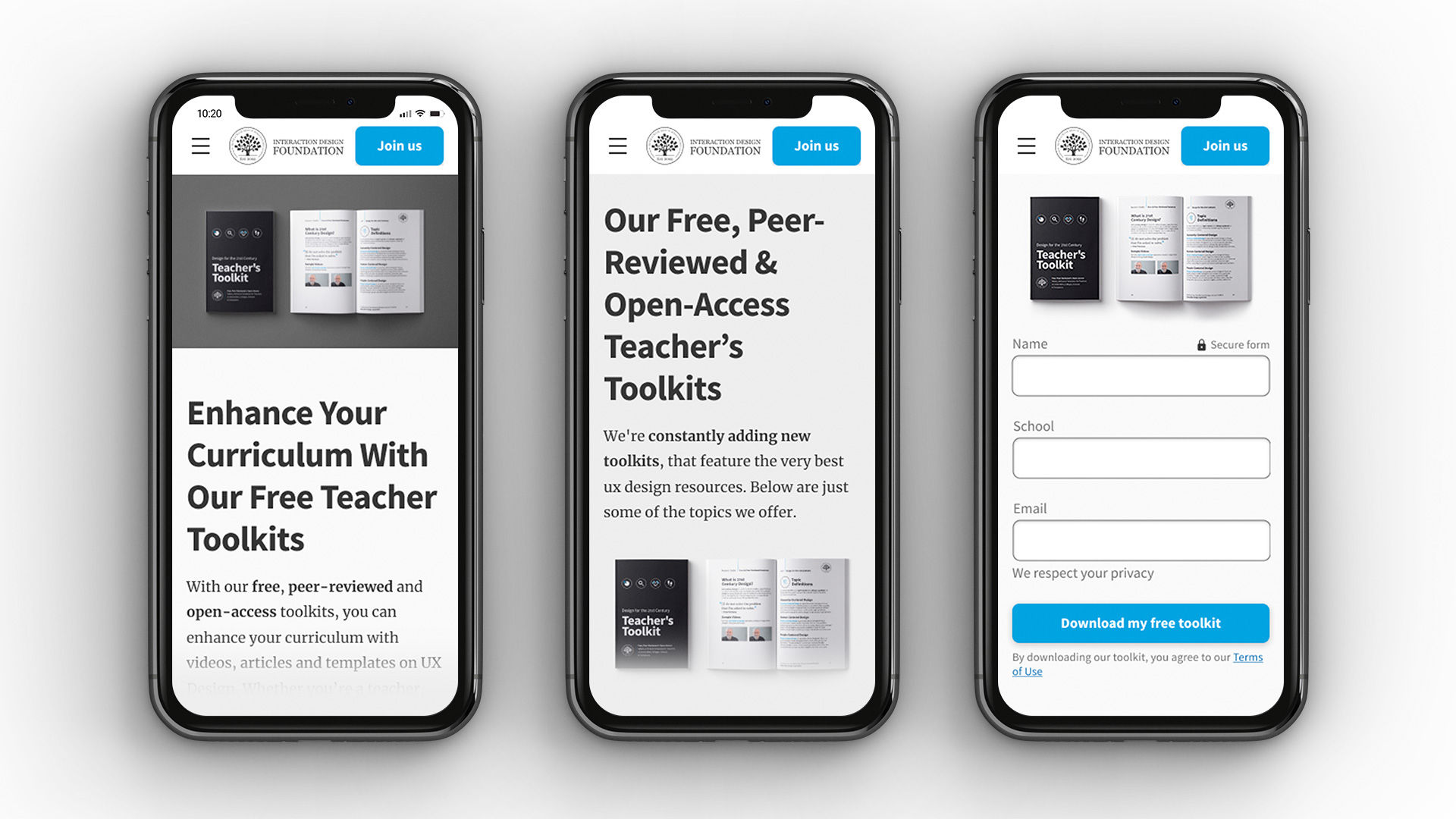

11. Mockups

Illustration depicting a mockup.

Even though mockups look like screenshots from a completed, real app, they are little more than images. Unfortunately, many clients seem to believe that at this stage, you must be really close to actually finishing the whole project, so be careful to make it abundantly clear that these are little more than good-looking visuals with no code behind them!

Mockups are fully polished visual designs sometimes rendered in realistic devices that include branding, colors, images and typography.

12. Design Systems

Illustration depicting a design system.

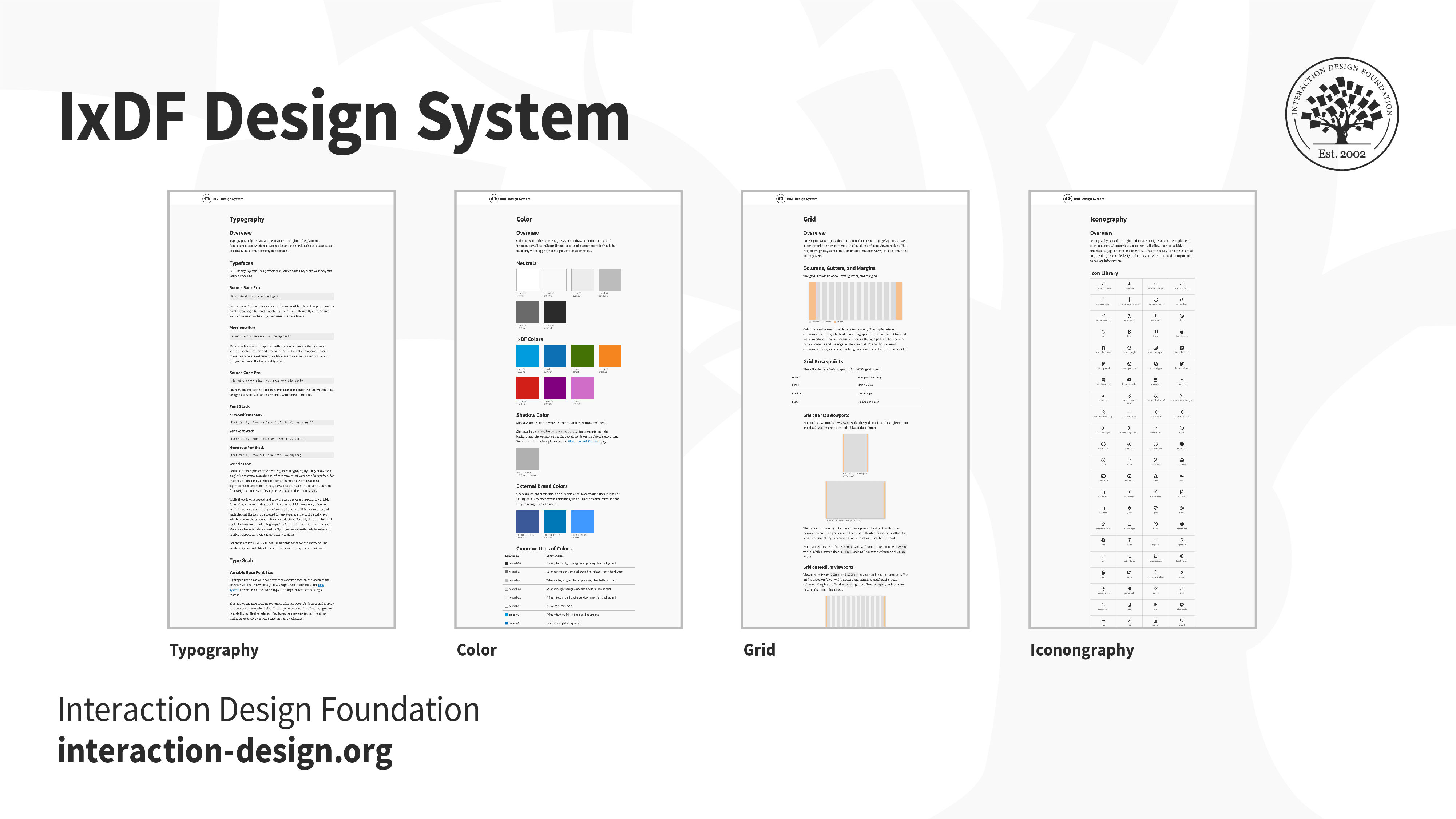

A design system is a library of reusable components and guidelines that people within a company can combine into interfaces and interactions. What goes into a design system and how it is implemented can vary quite a bit from company to company, depending on the size and maturity of the design practice and the needs of the product team.

At their core, design systems provide consistent styling and interaction guidelines for teams. A robust design system makes the process of assembling interfaces much faster, as designers do not need to create elements from scratch.

The IxDF Design System allows our team to build consistent, principle-based designs that solve our users’ needs. With a library of components and guidelines, the design system allows for closer and clearer collaboration between designers and developers.

Ideally, the different elements of a design system are actually pieces of code that developers can drop into interfaces in order to build a feature quicker or prototype faster. Other times, they’re simply design elements in a prototyping tool that designers can reuse.

Evaluation Deliverables

Being a UX designer doesn’t mean that you only work on new design-related deliverables! You must also evaluate your (and your peers’) work to ensure it meets the users’ and the organization’s objectives. Not only should you evaluate your work, but you also should look closely at what your competition is doing. This will help you learn and improve your designs.

13. Usability Reports

Illustration depicting a pie chart.

Once you have a design that is implemented (even if only as an interactive prototype), you can begin to run some evaluations of this design with real users. Evaluation can take many shapes and forms. You can have some users try out your design and then interview them, or work with them in a focus group: This is an example of qualitative evaluation. You could bring users into a lab and ask them to accomplish specific tasks with your prototype, while you measure things such as the number of errors, number of clicks, or time taken to complete the task. In the lab, you can use special equipment, such as eye-tracking cameras, to see where your users’ attention is spent while navigating a particular design. You could also ask them to perform the same task using prototypes that offer alternative design implementations, so you can compare them and see which design is better (known as A/B testing).

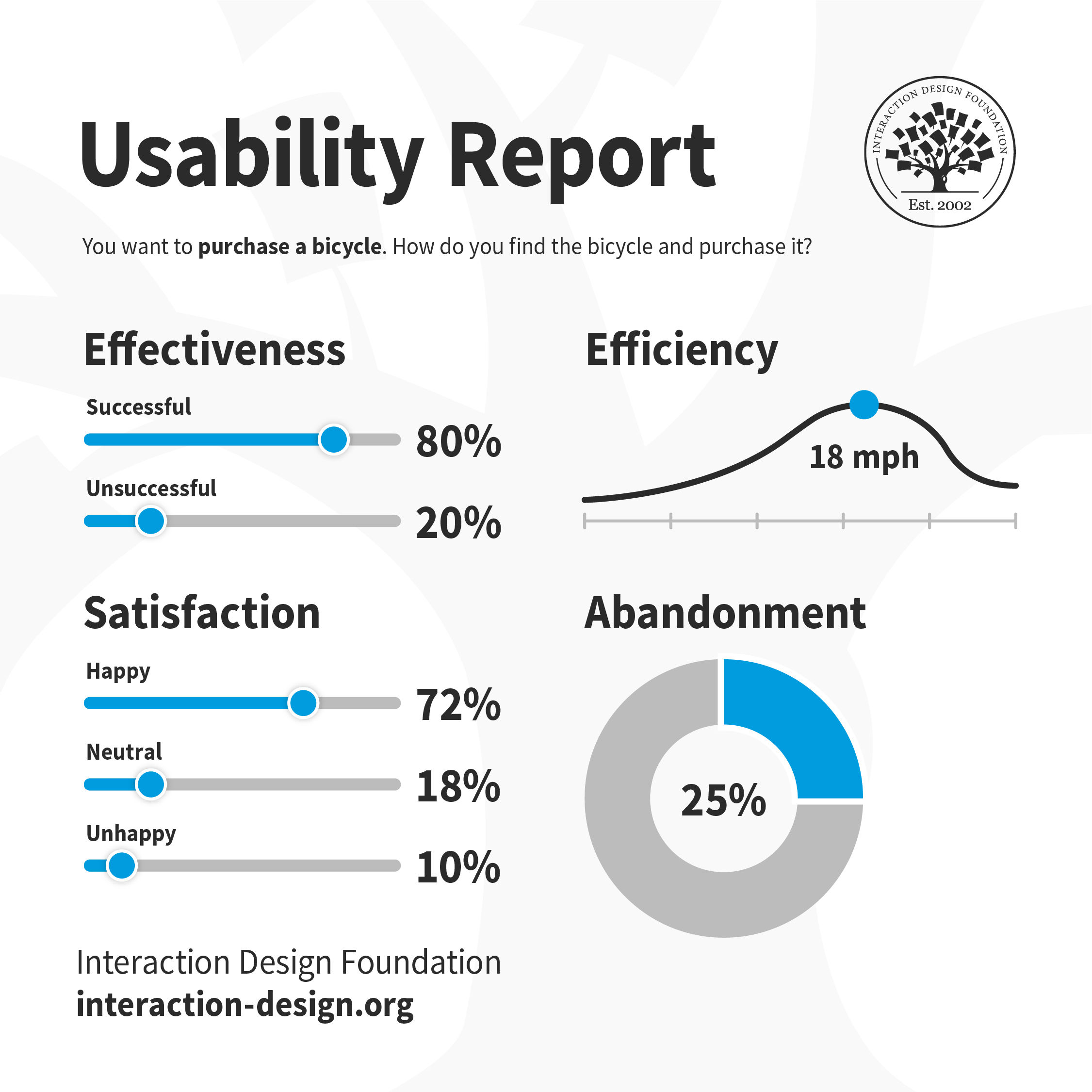

There are many ways to evaluate a design. No matter what you end up doing for evaluation, you will have to summarize your findings into a usability report. A complete usability report typically contains the following sections:

Background Summary: what you tested, where and when, the tools and equipment that you used and who was involved in the research

Methodology: how you went about the evaluation, what tasks you asked the users to perform, what data was collected, what scenarios were used, who the participants were and their demographics

Test Results: an analysis of all the data collected, including illustrations such as bar charts and textual descriptions of the findings, and user comments that might be particularly illustrative or enlightening. Depending on whom you are communicating the report to, this section may contain some more technical details, such as the type of statistical analyses used.

Findings and Recommendations: what do you recommend, based on the data that you collected and your findings? What worked well, what didn’t and why? State what should be done next to improve the design or move forward with the process.

Remember that a usability report might be directed towards a number of other roles in your project. Managers will probably just need an executive summary and a statement of how the findings impact the overall project timeline. Other designers will be more interested in how you carried out your evaluation and would like all the details. Developers are probably only interested in your findings and recommendations. Ensure that your report is structured and worded appropriately for its audience.

An example of a usability report compiled in summary form. The full details have been intentionally left out to focus on the outcomes. This type of infographic form is perfect for key stakeholders who don’t have time to review the full details of the report.

14. Analytics Report

Illustration depicting a bar graph.

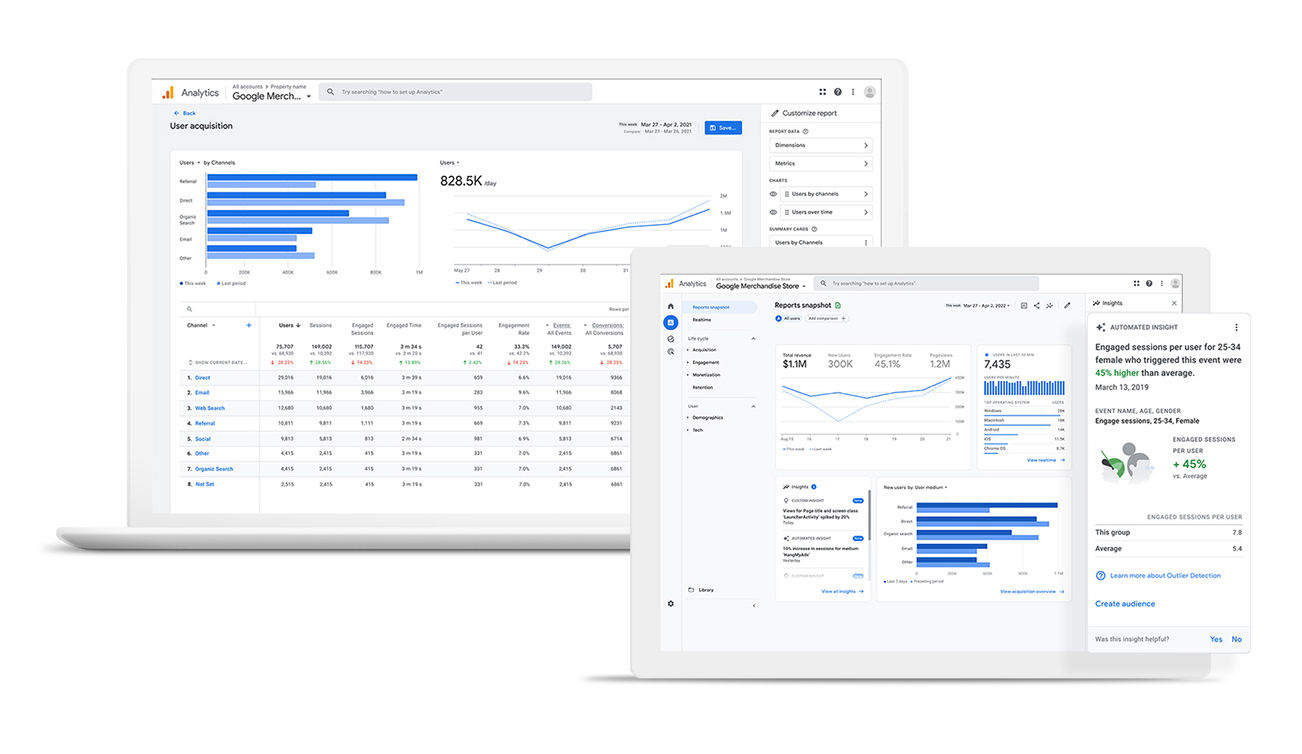

When a designed product has been released and has been running for a while, your company might make some usage analytics data available to you. Looking into this data may offer great insights into how to improve usability, particularly if this data contains users’ transitions and behaviors in your product.

For example, you might find that many users in an e-commerce website are not registering to complete a purchase. Does it mean that the registration process is not easy enough? Does it mean that they don’t see there is such an option? An analytics report contains the insights from this data and highlights areas where the design might be improved. While it is tempting to just put in the nice visuals and charts produced automatically by products such as Google Analytics, the UX designer’s job is not just to lay down the facts but also to interpret them. So, your report must contain the data, but also plausible explanations and recommendations on what to do. It’s also a useful record so that you can see the impact that design changes might have had on your website, after you have identified issues and attempted to address them.

An analytics report is more than just data and visuals. It should contain your own explanations for the observed emergent user behaviors and recommendations on where a design could be improved.

The Take Away

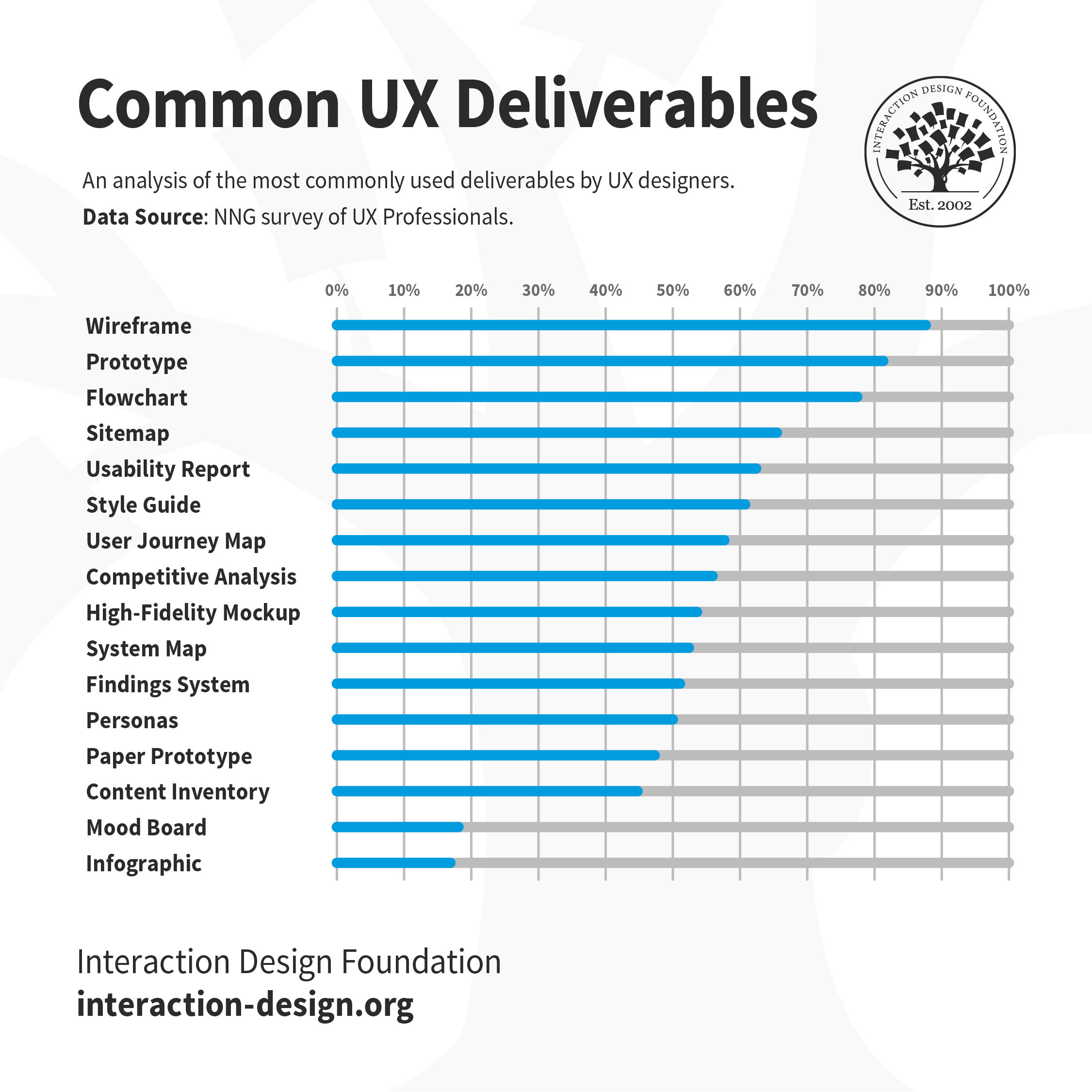

In a 2015 article for the Norman Nielsen Group, UX specialist Page Laubheimer analyzed the types of UX deliverables that UX designers most frequently reported as being asked to create as part of their role. Wireframes and prototypes were reported to be most commonly produced, followed by flowcharts, sitemaps, and usability/analytics reports.

An analysis of the most commonly produced UX deliverables, according to the Norman Nielsen Group. This shows the frequency with which UX professionals are asked to produce and share a specific deliverable. Deliverables with a lower frequency of demand are still produced, but are typically not shared as much with others.

These are what we consider to be “classic” UX deliverables, but one important point to keep in mind is that while these deliverables are produced and shared with others, many other types of deliverables will be produced but never shared (hence ranking lower in this study). In order to produce a wireframe, should a designer not have a complete understanding of the users and their needs? Often, management, clients and other team members are interested only in the type of deliverable that helps them advance their tasks, as well. Given this, the types of the deliverables you produce might need to be “tuned” to whom you are going to share them with, too.

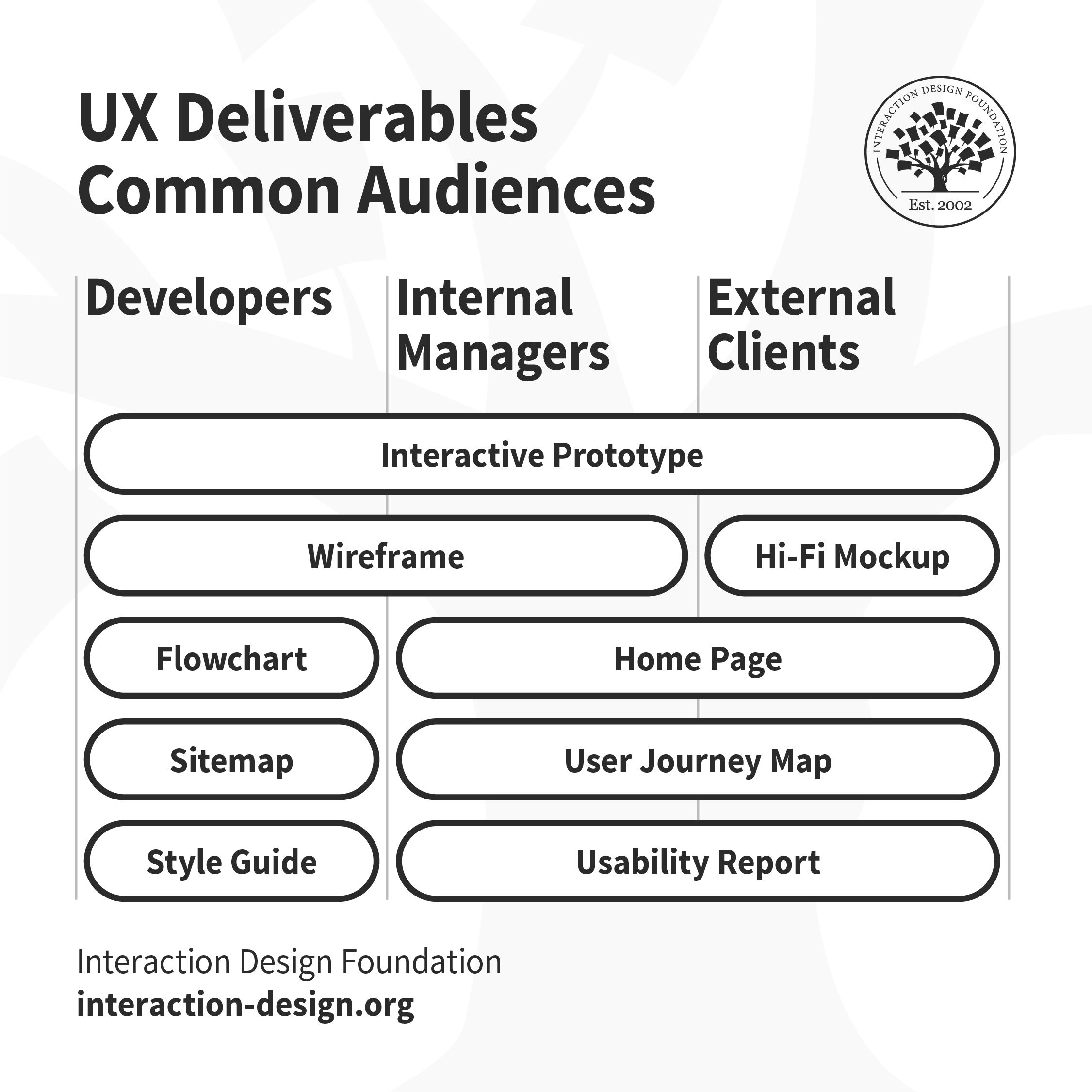

This chart shows the types of deliverables most frequently shared with other members of the development team and external clients. The interactive prototype is the one deliverable that everyone wants to see!

In your role as a UX designer, you will produce a wide variety of deliverables for different stages of the UX design process. Which deliverable you produce depends upon your team, the project, timelines and stakeholders. At the beginning of your UX career, you must learn and practice as many tools and methodologies as possible, and become familiar with all the types of UX deliverables out there. As you gain experience and work on different types of projects, you will get better at choosing the appropriate tools and tailor your UX design process (and deliverables) to suit the project.

References and Where to Learn More

Learn more about brainstorming and other idea-generation methods in the course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide

Image

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0