Personas are fictional characters, which you create based upon your research to represent the different user types that might use your service, product, site, or brand in a similar way. Creating personas will help you understand your users’ needs, experiences, behaviors and goals. Creating personas can help you step out of yourself. It can help you recognize that different people have different needs and expectations, and it can also help you identify with the user you’re designing for. Personas make the design task at hand less complex, they guide your ideation processes, and they can help you to achieve the goal of creating a good user experience for your target user group.

As opposed to designing products, services, and solutions based upon the preferences of the design team, it has become standard practice within many human-centered design disciplines to collate research and personify specific trends and patterns in the data as personas. Hence, personas do not describe real people, but you compose your personas based on actual data collected from multiple individuals. Personas add the human touch to what would largely remain cold facts in your research. Creating persona profiles of typical or atypical (extreme) users will help you understand patterns in your research, which synthesizes the types of people you seek to design for. Personas are also known as model characters or composite characters.

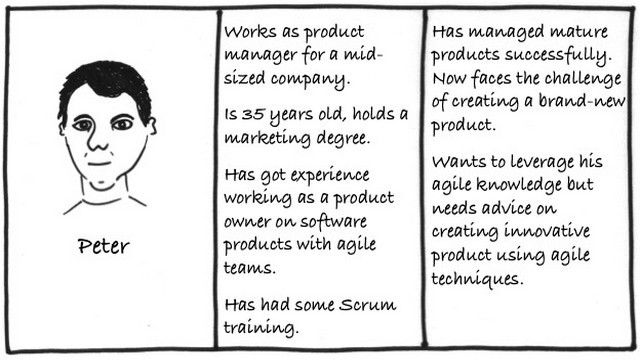

Personas provide meaningful archetypes which you can use to assess your design development against. Constructing personas will help you ask the right questions and answer those questions in line with the users you are designing for. For example, “How would Peter, Joe, and Jessica experience, react, and behave in relation to feature X or change Y within the given context?” and “What do Peter, Joe, and Jessica think, feel, do and say?” and “What are their underlying needs we are trying to fulfill?”

Personas in Design Thinking

In the design thinking process, designers will often start creating personas during the second phase, the Define phase. In the Define phase, Design Thinkers synthesize their research and findings from the very first phase, the Empathise phase. Using personas is just one method, among others, that can help designers move on to the third phase, the Ideation phase. The personas will be used as a guide for ideation sessions such as Brainstorm, Worst Possible Idea and SCAMPER.

Four Different Types of Personas

In her Interaction Design Foundation encyclopedia article, Personas, Ph.D. and specialist in personas, Lene Nielsen, describes four perspectives that your personas can take to ensure that they add the most value to your design project and the fiction-based perspective. Let’s take a look at each of them:

1. Goal-directed Personas

This persona cuts straight to the nitty-gritty. “It focusses on: What does my typical user want to do with my product?”. The objective of a goal-directed persona is to examine the process and workflow that your user would prefer to utilize to achieve their goals in interacting with your product or service. There is an implicit assumption that you have already done enough user research to recognize that your product has value to the user and that by examining their goals, you can bring their requirements to life. The goal-directed personas are based upon the perspectives of Alan Cooper, an American software designer and programmer who is widely recognized as the “Father of Visual Basic.”

2. Role-Based Personas

The role-based perspective is also goal-directed, and it also focuses on behavior. The personas of the role-based perspectives are massively data-driven and incorporate data from both qualitative and quantitative sources. The role-based perspective focuses on the user’s role in the organization. In some cases, our designs need to reflect upon the part that our users play in their organizations or wider lives. An examination of the roles that our users typically play in real life can help inform better product design decisions. Where will the product be used? What’s this role’s purpose? What business objectives are required of this role? Who else is impacted by the duties of this role? What functions are served by this role? Jonathan Grudin, John Pruitt, and Tamara Adlin are advocates for the role-based perspective.

3. Engaging Personas

“The engaging perspective is rooted in the ability of stories to produce involvement and insight. Through an understanding of characters and stories, it is possible to create a vivid and realistic description of fictitious people. The purpose of the engaging perspective is to move from designers seeing the user as a stereotype with whom they are unable to identify and whose life they cannot envision, to designers actively involving themselves in the lives of the personas. The other persona perspectives are criticized for causing a risk of stereotypical descriptions by not looking at the whole person, but instead focusing only on behavior.”

– Lene Nielsen

Engaging personas can incorporate both goal and role-directed personas, as well as the more traditional rounded personas. These engaging personas are designed so that the designers who use them can become more engaged with them. The idea is to create a 3D rendering of a user through the use of personas. The more people engage with the persona and see them as ’real’, the more likely they will be to consider them during the process design and want to serve them with the best product. These personas examine the emotions of the user, their psychology, backgrounds and make them relevant to the task at hand. The perspective emphasizes how stories can engage and bring the personas to life. One of the advocates for this perspective is Lene Nielsen.

One of the main difficulties of the persona method is getting participants to use it (Browne, 2011). In a short while, we’ll let you in on Lene Nielsen’s model, which sets out to cover this problem through a 10‑step process of creating an engaging persona.

You can download and print the “Engaging Persona” template, which you and your team can use as a guide:

4. Fictional Personas

The fictional persona does not emerge from user research (unlike the other personas), but it emerges from the experience of the UX design team. It requires the team to make assumptions based upon past interactions with the user base and products to deliver a picture of what, perhaps, typical users look like. There’s no doubt that these personas can be deeply flawed (and there are endless debates on just how flawed). You may be able to use them as an initial sketch of user needs. They allow for early involvement with your users in the UX design process, but they should not, of course, be trusted as a guide for your development of products or services.

10 steps to Creating Your Engaging Personas and Scenarios

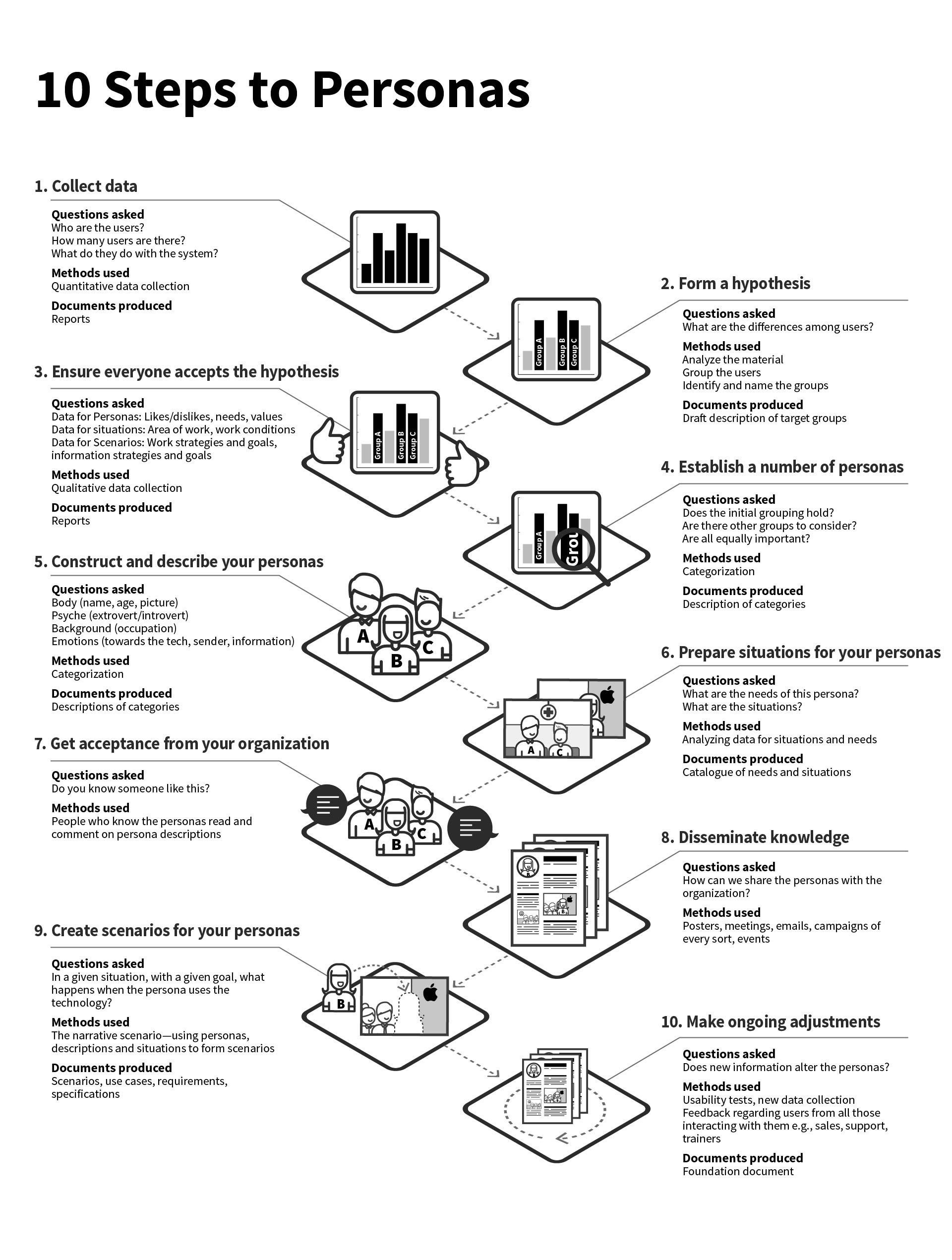

As described above, engaging personas can incorporate both goal and role-directed personas, as well as the more traditional rounded personas. Engaging personas emphasize how stories can engage and bring the personas to life. This 10-step process covers the entire process from preliminary data collection, through active use, to the continued development of personas. There are four main parts:

Data collection and analysis of data (steps 1, 2),

Persona descriptions (steps 4, 5),

Scenarios for problem analysis and idea development (steps 6, 9),

Acceptance from the organization and involvement of the design team (steps 3, 7, 8, 10).

The 10 steps are an ideal process, but sometimes it is not possible to include all the steps in the project. Here we outline the 10-step process as described by Lene Nielsen in her Interaction Design Foundation encyclopedia article, Personas.

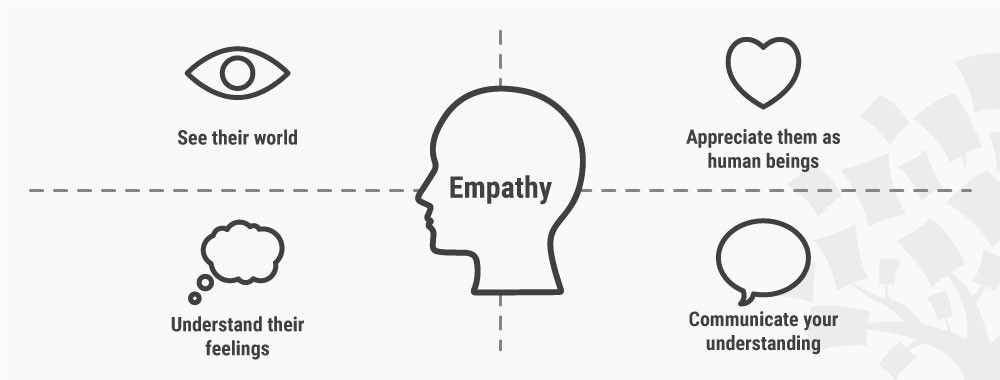

Collect data. Collect as much knowledge about the users as possible. Perform high-quality user research of actual users in your target user group. In Design Thinking, the research phase is the first phase, also known as the Empathise phase.

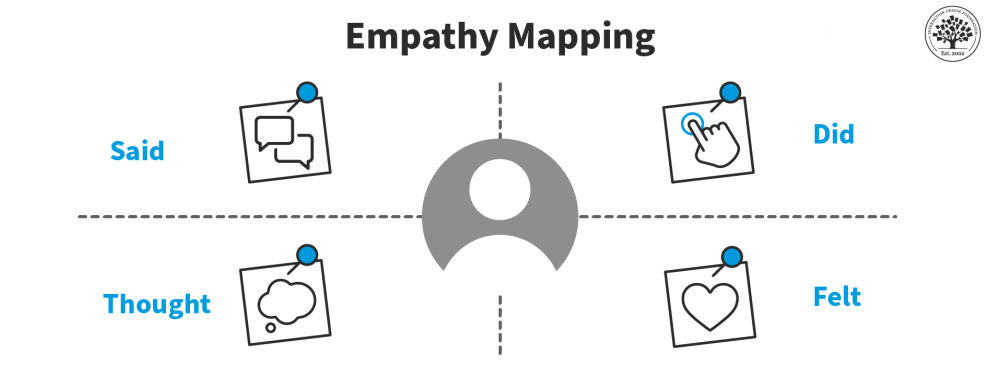

Form a hypothesis. Based upon your initial research, you will form a general idea of the various users within the focus area of the project, including the ways users differ from one another – For instance, you can use Affinity Diagrams and Empathy Maps.

Everyone accepts the hypothesis. The goal is to support or reject the first hypothesis about the differences between the users. You can do this by confronting project participants with the hypothesis and comparing it to existing knowledge.

Establish a number. You will decide upon the final number of personas, which it makes sense to create. Most often, you would want to create more than one persona for each product or service, but you should always choose just one persona as your primary focus.

Describe the personas. The purpose of working with personas is to be able to develop solutions, products and services based upon the needs and goals of your users. Be sure to describe personas in such a way as to express enough understanding and empathy to understand the users.

You should include details about the user’s education, lifestyle, interests, values, goals, needs, limitations, desires, attitudes, and patterns of behavior.

Add a few fictional personal details to make the persona a realistic character.

Give each of your personas a name.

Create 1–2 pages of descriptions for each persona.

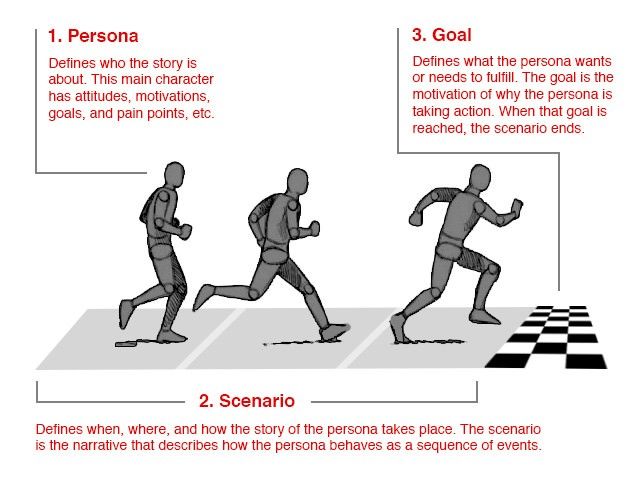

Prepare situations or scenarios for your personas. This engaging persona method is directed at creating scenarios that describe solutions. For this purpose, you should describe a number of specific situations that could trigger the use of the product or service you are designing. In other words, situations are the basis of a scenario. You can give each of your personas life by creating scenarios that feature them in the role of a user. Scenarios usually start by placing the persona in a specific context with a problem they want to or have to solve.

Obtain acceptance from the organization. It is a common thread throughout all 10 steps that the goal of the method is to involve the project participants. As such, as many team members as possible should participate in the development of the personas, and it is important to obtain the acceptance and recognition of the participants of the various steps. In order to achieve this, you can choose between two strategies: You can ask the participants for their opinion, or you can let them participate actively in the process.

Disseminate knowledge. In order for the participants to use the method, the persona descriptions should be disseminated to all. It is important to decide early on how you want to disseminate this knowledge to those who have not participated directly in the process, to future new employees, and to possible external partners. The dissemination of knowledge also includes how the project participants will be given access to the underlying data.

Everyone prepares scenarios. Personas have no value in themselves. Until the persona becomes part of a scenario – the story about how the persona uses a future product – it does not have real value.

Make ongoing adjustments. The last step is the future life of the persona descriptions. You should revise the descriptions on a regular basis. New information and new aspects may affect the descriptions. Sometimes you would need to rewrite the existing persona descriptions, add new personas, or eliminate outdated personas.

Example of How to Make a Persona Description – Step 5

© phot0geek, CC BY-SA 2.0

© phot0geek, CC BY-SA 2.0We will let you in on the details about our persona’s education, lifestyle, interests, values, goals, needs, limitations, desires, attitudes, and patterns of behavior. We’ve added a few fictional personal details to make our persona a realistic character and given her a name.

Hard Facts

Christie is living in a small apartment in Toronto, Canada. She’s 23 years old, single, studies ethnography, and works as a waiter during her free time.

Interests and Values

Christie loves to travel and experience other cultures. She recently spent her summer holiday working as a volunteer in Rwanda.

She loves to read books at home at night as opposed to going out to bars. She does like to hang out with a small group of friends at home or at quiet coffee shops. She doesn’t care too much about looks and fashion. What matters to her are values and motivations.

On an average day, she tends to drink many cups of tea, and she usually cooks her own healthy dishes. She prefers organic food; however, she’s not always able to afford it.

Computer, Internet and TV Use

Christie owns a MacBook Air, an iPad and an iPhone. She uses the internet for her studies to conduct the majority of her preliminary research and studies user reviews to help her decide upon which books to read and buy. Christie also streams all of her music, and she watches movies online since she does not want to own a TV. She thinks TV’s are outdated, and she does not want to waste her time watching TV shows, entertainment, documentaries, or news that she has not chosen and finds 100% interesting herself.

A Typical Day

Christie gets up at 7 am. She eats breakfast at home and leaves for university at 8.15 every morning.

Depending on her schedule, she studies by herself or attends a class. She has 15 hours of classes at Masters level every week, and she studies for 20 hours on her own.

She eats her lunch with a study friend or a small group.

She continues to study.

She leaves for home at 3 pm. Sometimes she continues to study for 2-3 hours at home.

Three nights a week, she works as a waitress at a small eco-restaurant from 6 pm to 10 pm.

Future Goals

Christie dreams of a future where she can combine work and travel. She wants to work in a third-world country, helping others who have not had the same luck of being born into a wealthy society. She’s not sure about having kids and a husband. At least it’s not on her radar just yet.

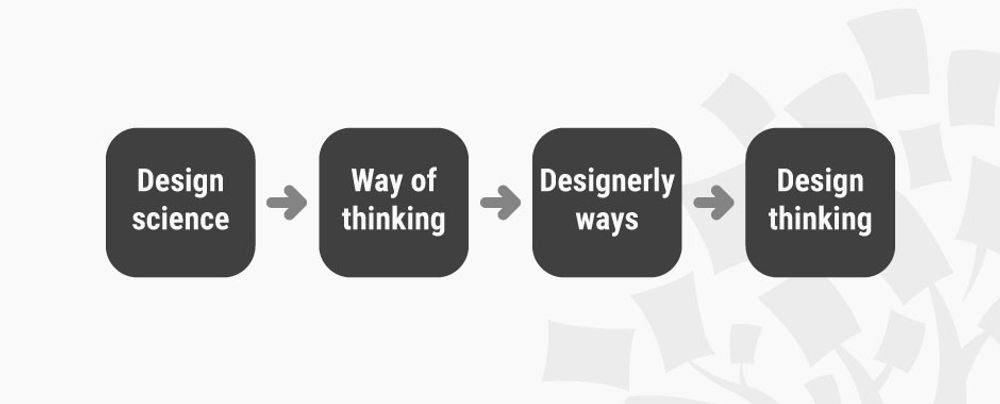

Know Your History

The method of developing personas stems from IT system development during the late 1990s, where researchers had begun reflecting on how you could best communicate an understanding of the users. Various concepts emerged, such as user archetypes, user models, lifestyle snapshots, and model users. In 1999, Alan Cooper published his successful book, The Inmates are Running the Asylum, where he, as the first person ever, described personas as a method we can use to describe fictitious users. There are a vast number of articles and books about personas. However, a unified understanding of one single way to apply the method doesn’t exist, nor does a definition of what a persona description should contain exactly.

The Take Away

Personas are fictional characters. You create personas based on your research to help you understand your users’ needs, experiences, behaviors and goals. Creating personas will help you identify with and understand the user you’re designing for. Personas make the design task at hand less complex, they will guide your ideation processes, and they will help you to achieve the goal of creating a good user experience for your target user group. Engaging personas emphasize how stories can engage and bring the personas to life. The 10-step process covers the entire process from the preliminary data collection, through active use, to the continued development of personas.

References & Where to Learn More

Course: “The Practical Guide to Usability”.

Nielsen, Lene, Personas. In: Soegaard, Mads and Dam, Rikke Friis (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd Ed. Aarhus, Denmark: The Interaction Design Foundation, 2013. See here.

Alan Cooper, The Inmates Are Running the Asylum, 1999

Personas can be used in conjunction with empathy mapping to provide a snapshot of a Persona’s experience as described in a Persona Empathy Mapping article by Nikki Knox on the Cooper.com Design & Strategy Agency’s Journal.

Atlanta-based photographer Jason Travis has created a series of Persona Portraits with their artifacts which illustrates the power of visually representing archetypal users, customers or personalities.

Hero Image: © Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0