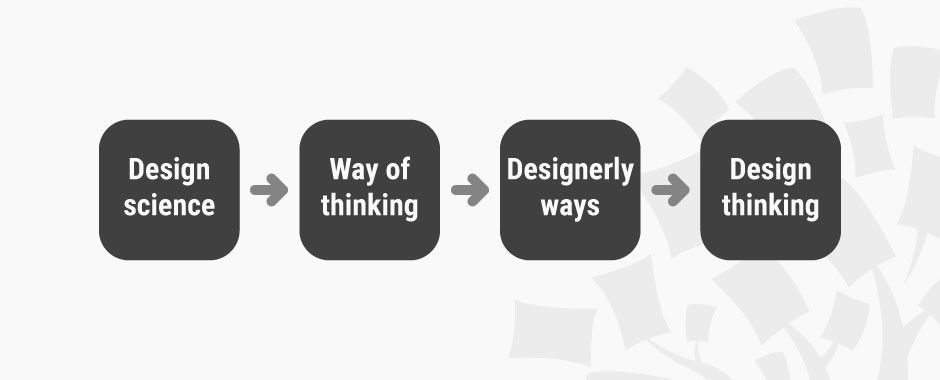

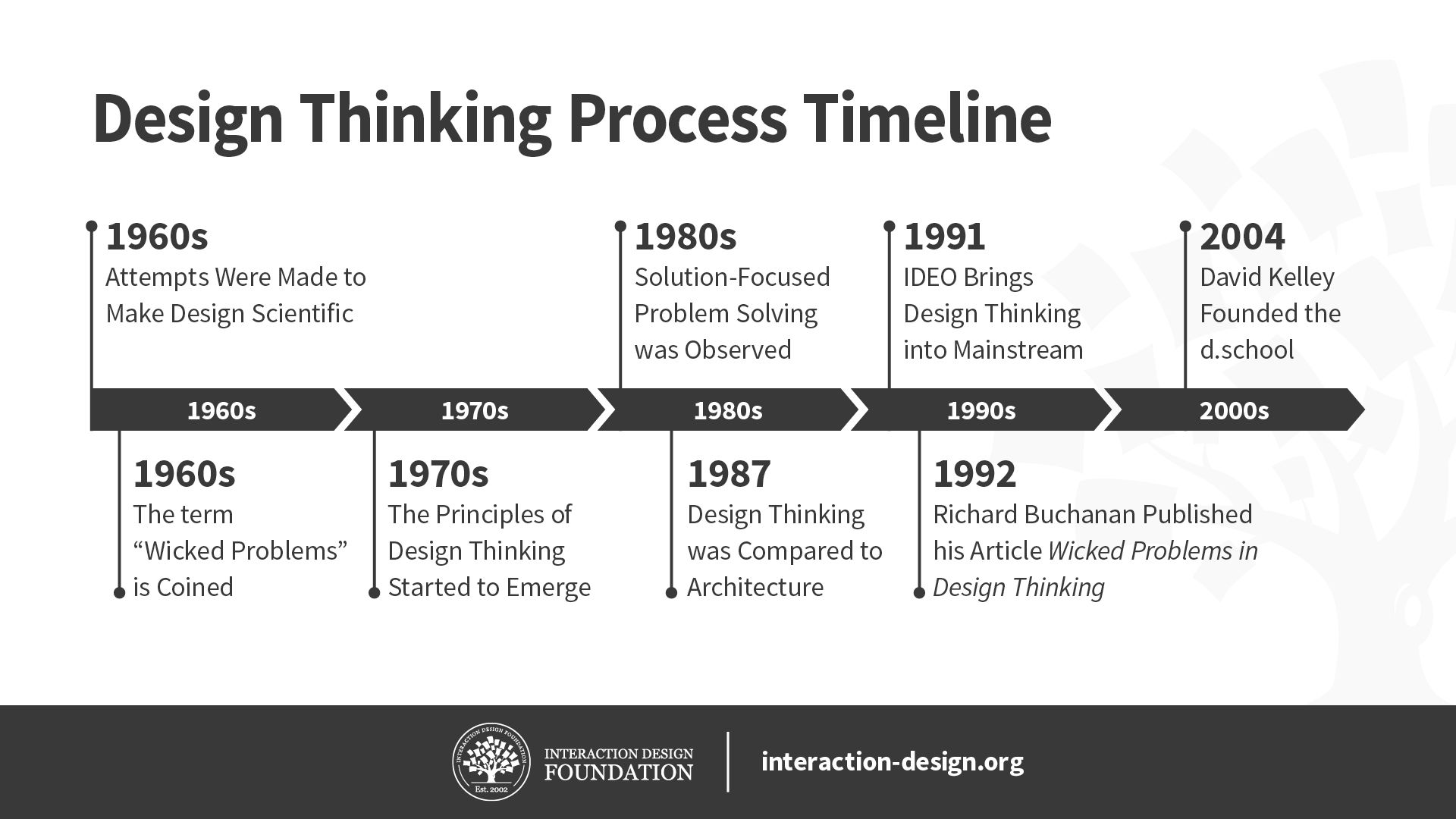

We need to appreciate the roots and origins of a concept to truly understand it—we need to know how it came to be. Let’s take a look at how design thinking emerged from an exploration of theory and practice to become one of the most effective ways to address the human, technological and strategic innovation needs of our time.

It’s virtually impossible to list all of the influential factors that led to the contemporary understanding of design theory, process and practice. Business analysts, engineers, scientists and creative individuals have studied the methods and processes behind innovation for decades. Early glimpses of design thinking date back to the 1950s and 1960s, although these references were more within the context of architecture and engineering — fields which struggled to grapple with the rapidly changing environment of that era.

World War II did have a profound effect on strategic thinking, however, and we have looked for new ways to solve complex problems ever since. In fact, we can say this huge world event fundamentally changed the way we apply ourselves to management, production and industrial design in the modern world. Let’s take a look at the history of design thinking, decade by decade, and see how the story unfolds from this point onwards.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The 1960s: Attempts Were Made to Make Design Scientific

In the ‘60s, people applied scientific methodology and processes in an attempt to understand every aspect of design—how it functions and what it’s influenced by, for example.

Nigel Cross—Emeritus Professor of Design Studies at The Open University, UK—unpicks the struggle that began to unfold in the early 1960s in the paper “Designerly ways of knowing: design discipline versus design science” (2001). Cross highlights statements made by radical technologist Buckminster Fuller, in which he refers to the “design science decade”:

"[Fuller] called for a ‘design science revolution', based on science, technology and rationalism, to overcome the human and environmental problems that he believed could not be solved by politics and economics."

– Nigel Cross

The struggle continued throughout the decade as further attempts were made to bring the field within the objective of rational sciences and, ultimately, make design scientific.

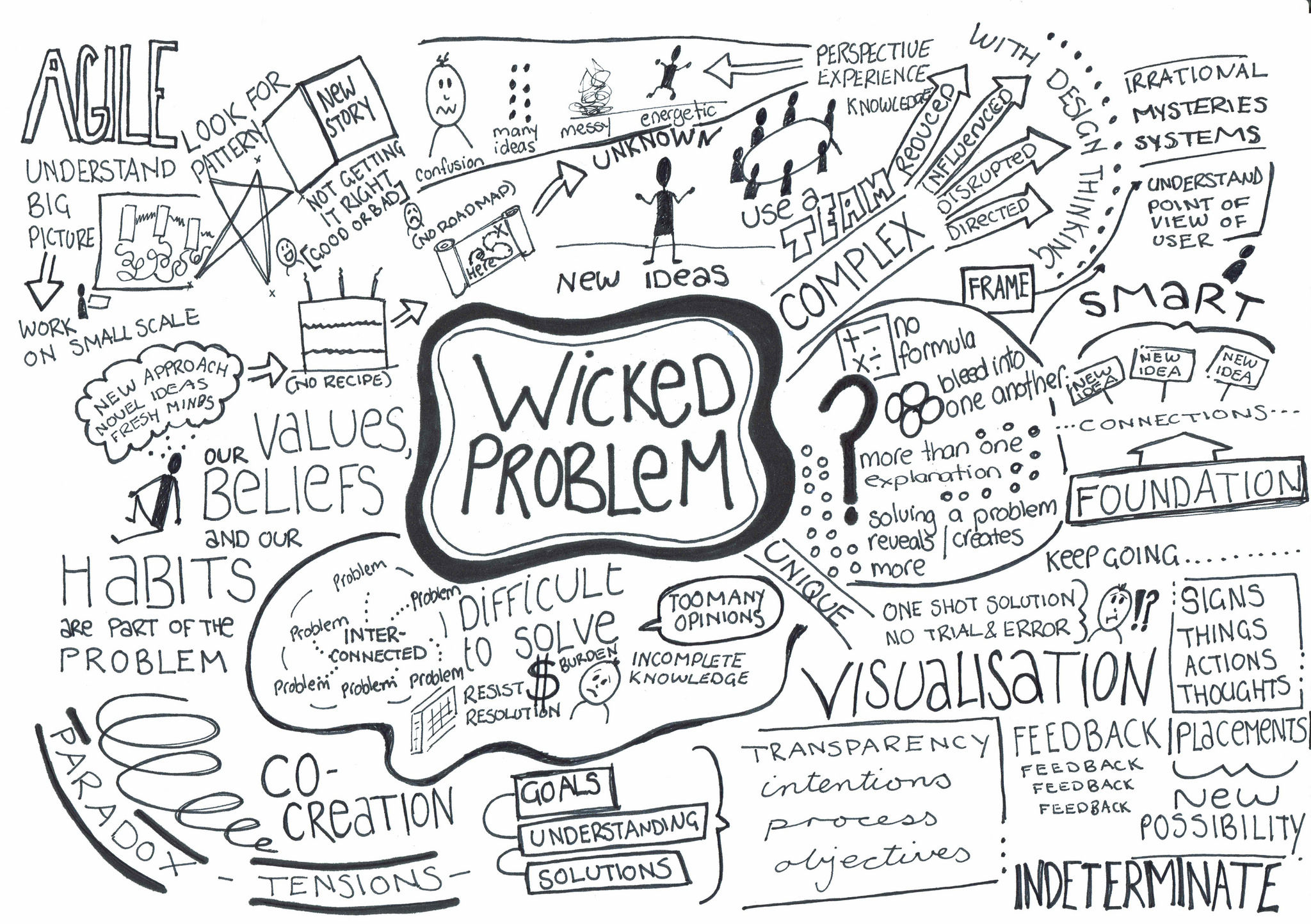

The term “Wicked Problems” is Coined

In the mid-1960s, Horst Rittel wrote and spoke extensively on the subject of problem-solving in design… so much so that he’s known as the design theorist who coined the term “wicked problem” to describe problems which are multidimensional and extremely complex. Rittel specifically focused on how design methodologies could be used to tackle wicked problems and how these methodologies were influential to the work of many design practitioners and academics of the time.

Horst Rittel is known as the design theorist who coined the term “wicked problem” after he wrote and spoke extensively on the topic of problem-solving in the 1960s.

© LoraCBR, CC BY 2.0.

Wicked problems are at the very heart of design thinking because it is precisely these complex and multidimensional problems that require a collaborative methodology to gain a deep understanding of humans’ needs, motivations and behavior.

The 1970s: The Principles of Design Thinking Started to Emerge

Cognitive scientist and Nobel Prize laureate Herbert A. Simon was the first to mention design as a way of thinking in his 1969 book, The Sciences of the Artificial. He then went on to contribute many ideas throughout the 1970s which are now regarded as principles of design thinking.

Simon is noted to have spoken about rapid prototyping and testing through observation, for example—concepts which form the core of many design and entrepreneurial processes today, including two of the major phases in the typical design thinking process. Simon touched on the subject of prototyping as early as 1969 when he stated the following in The Sciences of the Artificial:

"To understand them, the systems had to be constructed, and their behaviour observed."

– Herbert Simon

Early research in the field of artificial intelligence, such as the work by Herbert Simon, Allen Newell and Cliff Shaw involving chess software, also resulted in a better understanding of design as a way of thinking.

Image courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University.

What’s more, a large proportion of his work was focused on the development of artificial intelligence and whether human forms of thinking could be synthesized—a topic which is very prevalent in the design world today.

Robert H. McKim, Emeritus Professor of Mechanical Engineering, also referred to the notion of design thinking in his 1973 book, Experiences in Visual Thinking. McKim differed from Simon in that he is best described as an artist and engineer—he focused his energies more on the impact visual thinking had on our ability to understand things and solve problems. McKim’s book unpicks various aspects of the visual thinking and design methods used to solve problems. He places an emphasis on the combination of left and right brain modes of thinking, to bring about a more holistic form of problem-solving. The ideas discussed in his book ultimately underpin the design thinking methodology we use today.

The 1980s: Solution-Focused Problem-Solving was Observed

In 1982, Nigel Cross continued to make history in the design thinking world when he discussed the nature of how designers solve problems in his seminal paper “Designerly Ways of Knowing”. (Please note, this is not to be confused with his series of articles and papers similarly titled “Designerly Ways of Knowing”, published much later in the 2000s). In his 1982 paper, Cross compared designers’ problem-solving processes to the non-design-related solutions we develop to problems in our everyday lives.

Bryan Lawson, Emeritus Professor at the School of Architecture, University of Sheffield, UK, also discussed the insights he’d gathered from a series of interesting tests. The main goal of the tests was to compare the methods used by scientists and architects when they attempted to solve the same ambiguous problem.

Bryan Lawson asked architectural and science students to arrange colored blocks according to a set of rules. What he discovered was incredibly interesting and contributed to his theories around the “designerly” way of problem-solving.

© Bryan Lawson 1980:Fair use.

Lawson conducted the tests on postgraduate architectural students (i.e., the “designers”) and postgraduate science students (the “scientists”). The problem he set for each group required the students to arrange colored blocks according to a set of rules—some of which were unknown to the students.

The results were as follows:

Scientists | Designers |

|---|---|

Systematically explored every possible combination of blocks. | Quickly created multiple arrangements of colored blocks. |

Formulated a hypothesis about the fundamental rule they should follow to produce the optimal arrangement of blocks. | Tested their arrangement of blocks to see if it fit the rules. |

Lawson concluded that the scientists were problem-focused problem-solvers whereas the designers were solution-focused.

The designers chose to generate a large number of solutions and eliminate those which did not work. Cross deems this solution-focused mindset a core concept in the “designerly” way of problem-solving. According to Cross:

"A central feature of design activity, then, is its reliance on generating fairly quickly a satisfactory solution, rather than on any prolonged analysis of the problem. In [Herbert] Simon’s inelegant term, it is a process of ‘satisficing’ rather than optimising; producing any one of what might well be a large range of satisfactory solutions rather than attempting to generate the one hypothetically-optimum solution. This strategy has been observed in other studies of design behaviour, including architects, urban designers, and engineers."

– Nigel Cross, 1982

1987: Design Thinking was Compared to Architecture Once Again

Peter Rowe, then Director of Urban Design Programs at Harvard, published his book Design Thinking in 1987. It focuses on the way architectural designers approach their tasks through an inquisitive lens.

"This book is an attempt to fashion a generalized portrait of design thinking. A principal aim will be to account for the underlying structure and focus of inquiry directly associated with those rather private moments of “seeking out,” on the part of designers, for the purpose of inventing or creating buildings and urban artifacts."

– Peter Rowe (1987)

As you can see, the progression of design thinking as a subject made its journey through various fields of specialization over the decades. Thinkers within those various fields explored the cognitive processes within the scope of their own knowledge until design thinking finally became a separate concept and moved into a space of its own.

The 1990s to the Present

1991

It is widely accepted that IDEO is one of the companies that brought design thinking into the mainstream. They developed their own customer-friendly terminology, steps and toolkits over the years, and made the process more accessible to those not schooled in design methodology.

IDEO have developed their own design thinking terminology, steps and toolkits. This picture was taken at one of their Make-a-thons—two fun, intense days where groups of people craft, hack and build human-centered design solutions to real-world problems.

© IDEO, CC BY-SA 2.0.

1992

Richard Buchanan, then Head of Design at Carnegie Mellon University, published his article “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking”, which discussed the origins of design thinking. In the article, he discusses how the sciences developed over time to become more and more cut off from each other until they finally became specializations in their own right. He clarifies that design thinking is a means to integrate these highly specialized fields of knowledge so they can be jointly applied to the new problems we face in the world today—and from a holistic perspective.

2004

David Kelley founded the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford—commonly known as the d.school. The d.school has made the development, teaching and implementation of design thinking one of its central goals since inception, and it serves as a source of huge inspiration to design thinkers across the world, including us here at the Interaction Design Foundation.

A day in the life of a pop-up class at Stanford d.School.

© Stanford d.School blog: Public License. Source.

Present Day

At present, the design thinking movement is rapidly gaining ground—with pioneers like IDEO and the d.school paving out a path for others to follow. Other prestigious universities, business schools and forward-thinking companies have adopted the design thinking methodology to varying degrees, and have sometimes even re-interpreted it to suit their specific context or brand values.

The understanding and use of the term 'wicked problems' has matured too, and Human-Centered Design pioneers and leaders like Don Norman: Father of User Experience design, author of the legendary book The Design of Everyday Things, co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group, and former VP of the Advanced Technology Group at Apple, now prefer the term 'complex socio-technical systems'.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

The Take Away

Both the Industrial Revolution and World War II pushed the boundaries of what we thought was technologically possible. Engineers, architects and industrial designers—as well as cognitive scientists—then began to converge on the issues of collective problem-solving, driven by the significant societal changes that took place at that time.

Design thinking emerged—or, should we say, converged—out of the muddy waters of this chaos from the ’50s and ’60s onwards. The process started to combine the human, technological and strategic needs of our times, and progressively developed over the decades to become the leading innovation methodology it is today. Design thinking continues to gain ground across a wide range of industries and is still explored and enhanced by those at the forefront of the field.

References & Where to Learn More

Ready to shape the future, not just watch it happen? Join the Father of UX Design, Don Norman, in his two courses, Design for the 21st Century and Design for a Better World, and turn your care for people and the planet into design skills that elevate your impact, your confidence, and your career.

Images

Hero Image: © Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.