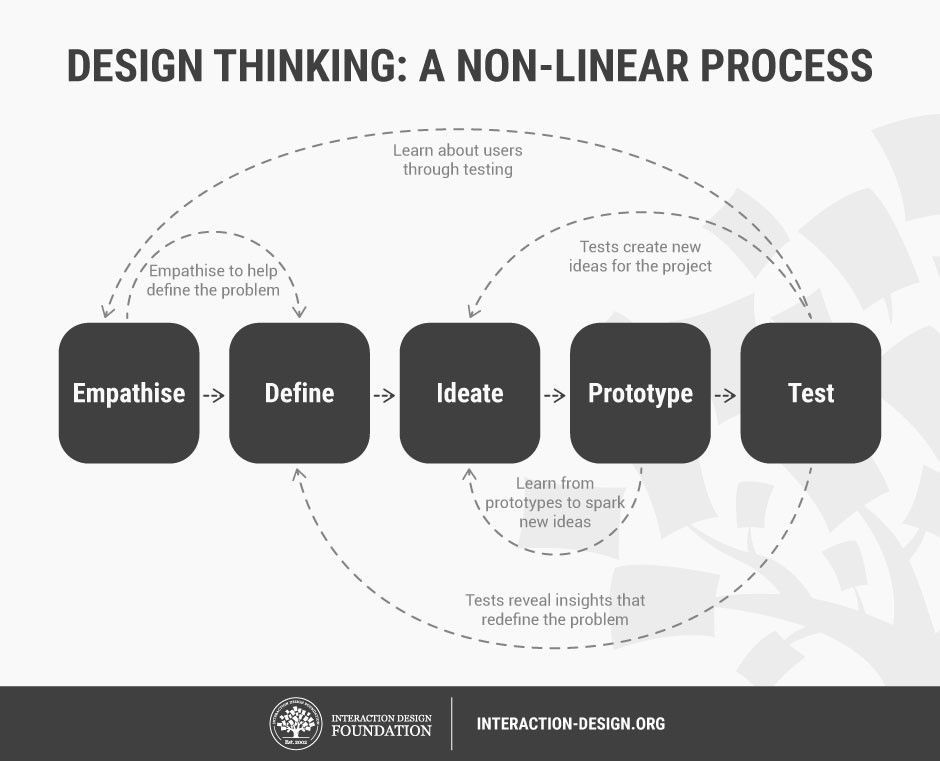

An integral part of the Design Thinking process is the definition of a meaningful and actionable problem statement, which the design thinker will focus on solving. This is perhaps the most challenging part of the Design Thinking process, as the definition of a problem (also called a design challenge) will require you to synthesise your observations about your users from the first stage in the Design Thinking process, which is called the Empathise stage.

When you learn how to master the definition of your problem, problem statement, or design challenge, it will greatly improve your Design Thinking process and result. Why? A great definition of your problem statement will guide you and your team’s work and kick start the ideation process in the right direction. It will bring about clarity and focus to the design space. On the contrary, if you don’t pay enough attention to defining your problem, you will work like a person stumbling in the dark.

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

In the Define stage you synthesise your observations about your users from the first stage, the Empathise stage. A great definition of your problem statement will guide you and your team’s work and kick start the ideation process (third stage) in the right direction. The five stages are not always sequential — they do not have to follow any specific order and they can often occur in parallel and be repeated iteratively. As such, the stages should be understood as different modes that contribute to a project, rather than sequential steps.

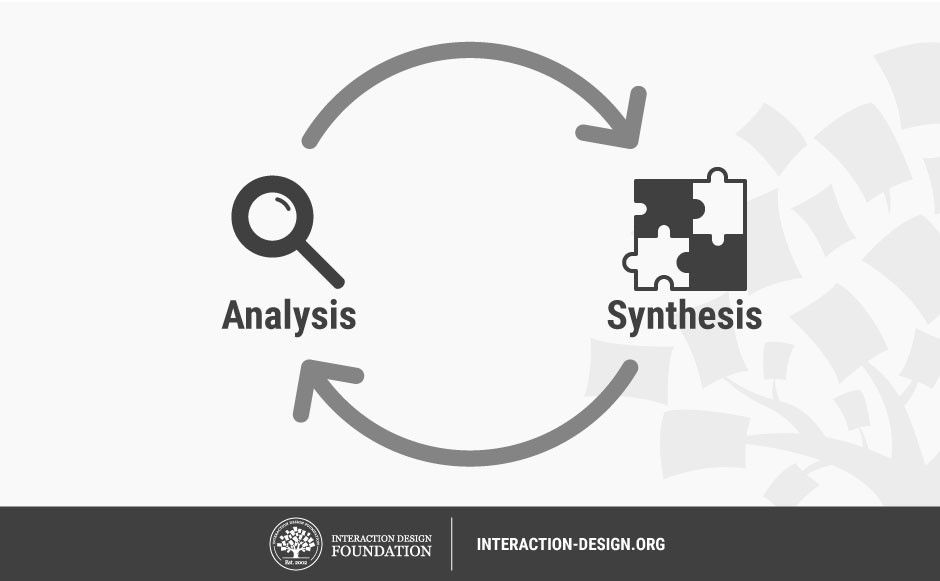

Analysis and Synthesis

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

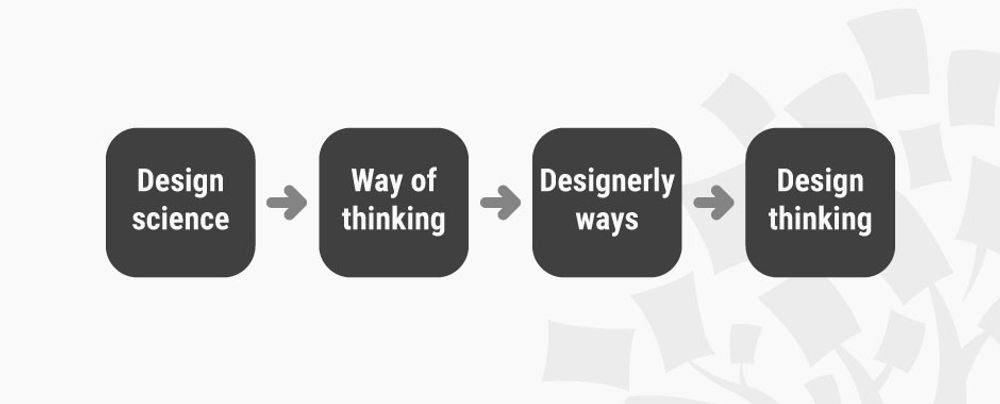

Before we go into what makes a great problem statement, it’s useful to first gain an understanding of the relationship between analysis and synthesis that many design thinkers will go through in their projects. Tim Brown, CEO of the international design consultancy firm IDEO, wrote in his book Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation, that analysis and synthesis are “equally important, and each plays an essential role in the process of creating options and making choices.”

Analysis is about breaking down complex concepts and problems into smaller, easier-to-understand constituents. We do that, for instance, during the first stage of the Design Thinking process, the Empathise stage, when we observe and document details that relate to our users. Synthesis, on the other hand, involves creatively piecing the puzzle together to form whole ideas. This happens during the Define stage when we organise, interpret, and make sense of the data we have gathered to create a problem statement.

Although analysis takes place during the Empathise stage and synthesis takes place during the Define stage, they do not only happen in the distinct stages of Design Thinking. In fact, analysis and synthesis often happen consecutively throughout all stages of the Design Thinking process. Design thinkers often analyse a situation before synthesising new insights, and then analyse their synthesised findings once more to create more detailed syntheses.

What Makes a Good Problem Statement?

A problem statement is important to a Design Thinking project, because it will guide you and your team and provides a focus on the specific needs that you have uncovered. It also creates a sense of possibility and optimism that allows team members to spark off ideas in the Ideation stage, which is the third and following stage in the Design Thinking process. A good problem statement should thus have the following traits. It should be:

Human-centered. This requires you to frame your problem statement according to specific users, their needs and the insights that your team has gained in the Empathise phase. The problem statement should be about the people the team is trying to help, rather than focusing on technology, monetary returns or product specifications.

Broad enough for creative freedom. This means that the problem statement should not focus too narrowly on a specific method regarding the implementation of the solution. The problem statement should also not list technical requirements, as this would unnecessarily restrict the team and prevent them from exploring areas that might bring unexpected value and insight to the project.

Narrow enough to make it manageable. On the other hand, a problem statement such as , “Improve the human condition,” is too broad and will likely cause team members to easily feel daunted. Problem statements should have sufficient constraints to make the project manageable.

As well as the three traits mentioned above, it also helps to begin the problem statement with a verb, such as “Create”, “Define”, and “Adapt”, to make the problem become more action-oriented.

How to Define a Problem Statement

Methods of interpreting results and findings from the observation oriented Empathise phase include:

Space Saturate and Group and Affinity Diagrams – Clustering and Bundling Ideas and Facts

Author/Copyright holder: Giorgio Montersino. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

Author/Copyright holder: Giorgio Montersino. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

In space saturate and group, designers collate their observations and findings into one place, to create a collage of experiences, thoughts, insights, and stories. The term 'saturate' describes the way in which the entire team covers or saturates the display with their collective images, notes, observations, data, experiences, interviews, thoughts, insights, and stories in order to create a wall of information to inform the problem-defining process. It will then be possible to draw connections between these individual elements, or nodes, to connect the dots, and to develop new and deeper insights, which help define the problem(s) and develop potential solutions. In other words: go from analysis to synthesis.

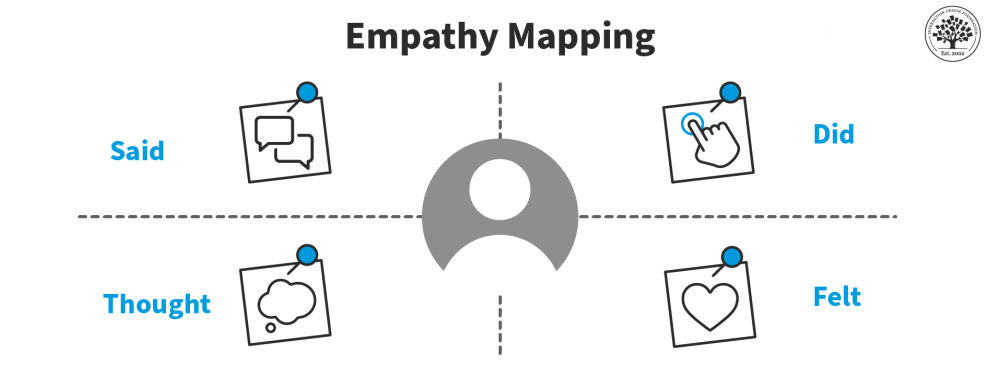

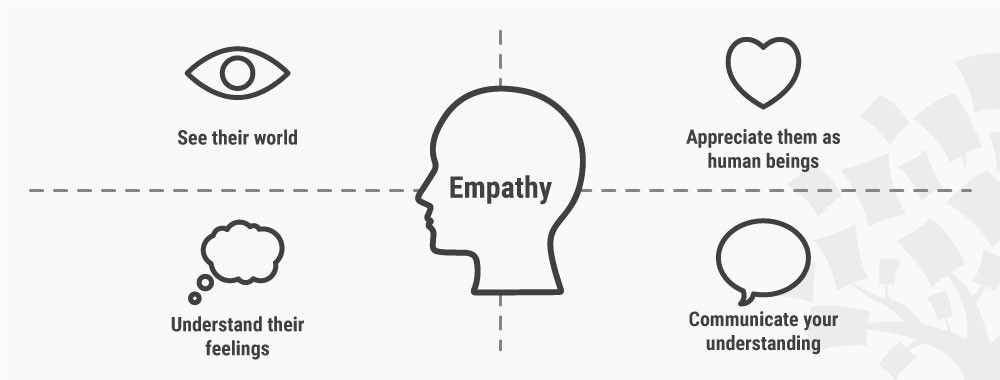

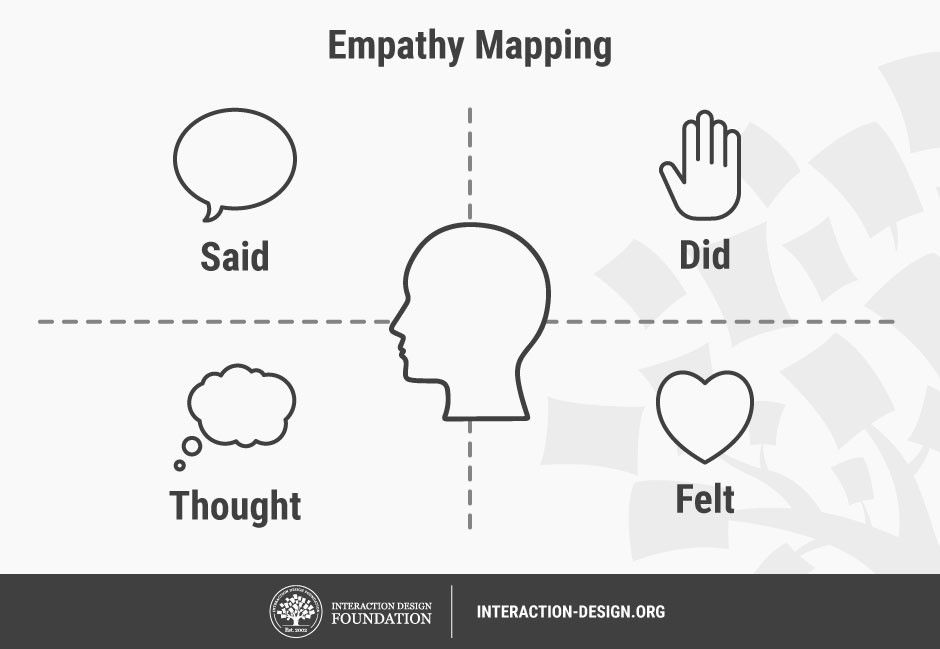

Empathy Mapping

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

An empathy map consists of four quadrants laid out on a board, paper or table, which reflect the four key traits that the users demonstrated/possessed during the observation stage. The four quadrants refer to what the users: Said, Did, Thought, and Felt. Determining what the users said and did are relatively easy; however, determining what they thought and felt is based on careful observation of how they behaved and responded to certain activities, suggestions, conversations etc. (including subtle cues such as body language displayed and the tone of voice used).

Point Of View – Problem Statement

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

A Point Of view (POV) is a meaningful and actionable problem statement, which will allow you to ideate in a goal-oriented manner. Your POV captures your design vision by defining the RIGHT challenge to address in the ideation sessions. A POV involves reframing a design challenge into an actionable problem statement. You articulate a POV by combining your knowledge about the user you are designing for, his or her needs and the insights which you’ve come to know in your research or Empathise mode. Your POV should be an actionable problem statement that will drive the rest of your design work.

You articulate a POV by combining these three elements – user, need, and insight. You can articulate your POV by inserting your information about your user, the needs and your insights in the following sentence:

[User . . . (descriptive)] needs [need . . . (verb)] because [insight. . . (compelling)]

“How Might We” Questions

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

When you’ve defined your design challenge in a POV, you can start to generate ideas to solve your design challenge. You can start using your POV by asking a specific question starting with: “How Might We” or “in what ways might we”. How Might We (HMW) questions are questions that have the potential to spark ideation sessions such as brainstorms. They should be broad enough for a wide range of solutions, but narrow enough that specific solutions can be created for them. “How Might We” questions should be based on the observations you’ve gathered in the Empathise stage of the Design Thinking process.

For example, you have observed that youths tend not to watch TV programs on the TV at home, some questions which can guide and spark your ideation session could be:

How might we make TV more social, so youths feel more engaged?

How might we enable TV programs to be watched anywhere, at anytime?

How might we make watching TV at home more exciting?

The HMW questions open up to Ideation sessions where you explore ideas, which can help you solve your design challenge in an innovative way.

Why-How Laddering

"As a general rule, asking 'why’ yields more abstract statements and asking 'how’yields specific statements. Often times abstract statements are more meaningful but not as directly actionable, and the opposite is true of more specific statements."

– d.school, Method Card, Why-How Laddering

For this reason, during the Define stage designers seek to define the problem, and will generally ask why. Designers will use why to progress to the top of the so-called Why-How Ladder where the ultimate aim is to find out how you can solve one or more problems. Your How Might We questions will help you move from the Define stage and into the next stage in Design Thinking, the Ideation stage, where you start looking for specific innovative solutions. In other words you could say that the Why-How Laddering starts with asking Why to work out How they can solve the specific problem or design challenge.

The Take Away

The second stage in a typical Design Thinking process is called the Define phase. It involves collating data from the observation stage (first stage called Empathise) to define the design problems and challenges. By using methods for synthesising raw data into a meaningful and usable body of knowledge — such as empathy mapping and space saturate and group — we will be able to create an actionable design problem statement or Point of View that inspire the generation of ideas to solve it. The How Might We questions open up to Ideation sessions where you explore ideas, which can help you solve your design challenge in an innovative way.

References & Where to Learn More

Course: “Design Thinking - The Ultimate Guide”.

d.school: Space Saturation and Group.

d.school: Empathy Map.

d.school: “How might we” questions.

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: gdsteam. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0