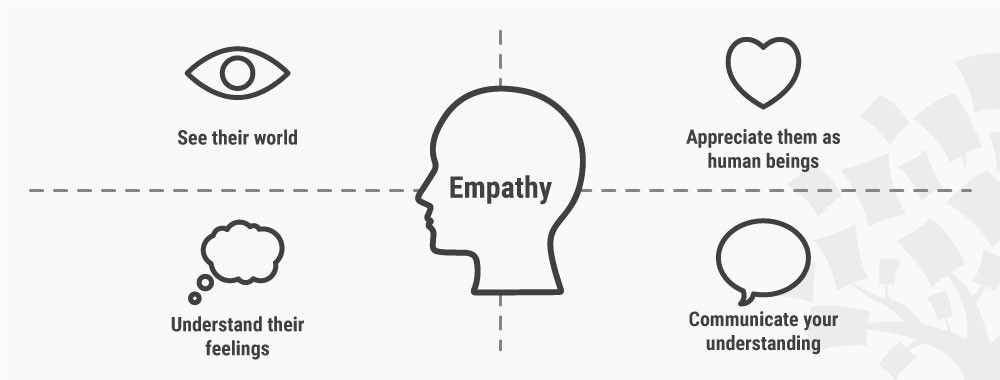

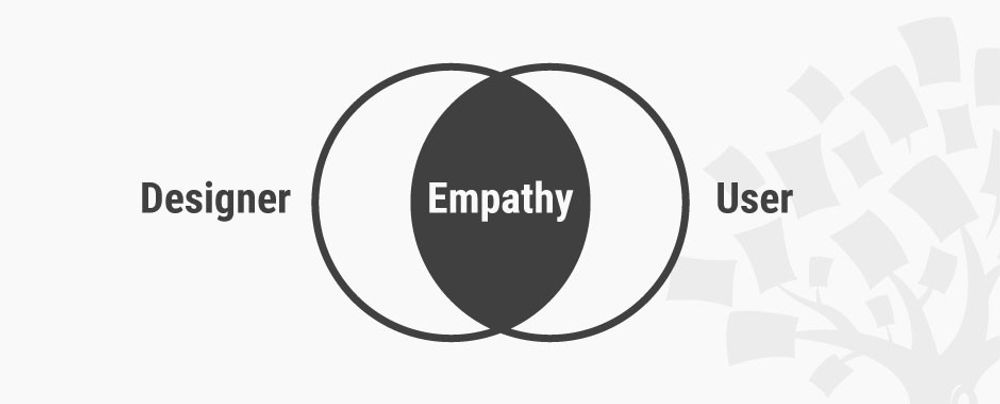

Design Thinking cannot begin without a deeper understanding of the people you are designing for. In order to gain those insights, it is important for you as a design thinker to empathize with the people you’re designing for so that you can understand their needs, thoughts, emotions and motivations. The good news is that you have a wide range of methods at your command for learning more about people. The even better news is this: with enough mindfulness and experience, anyone can become a master at empathizing with people.

"Engaging with people directly reveals a tremendous amount about the way they think and the values they hold. Sometimes these thoughts and values are not obvious to the people who hold them. A deep engagement can surprise both the designer and the designee by the unanticipated insights that are different from what they actually do - are strong indicators of their deeply held beliefs about the way the world is."

– d. School Bootcamp Bootleg, 2013

Developing Empathy towards People

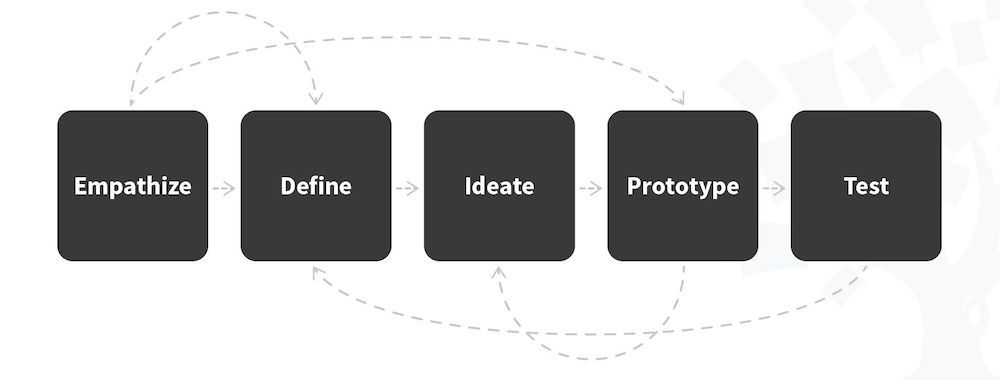

The first stage (or mode) of the Design Thinking process involves developing a sense of empathy towards the people you are designing for, to gain insights into what they need, what they want, how they behave, feel, and think, and why they demonstrate such behaviors, feelings, and thoughts when interacting with products in a real-world setting.

![]()

Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

The five stages of Design Thinking are not always sequential — they do not have to follow any specific order, and you will find they can often occur in parallel and you can repeat them iteratively. As such, the stages should be understood as different modes that contribute to a project, rather than sequential steps. However, most projects begin with an “Empathizing” phase.

To gain empathy towards people, we as design thinkers often observe them in their natural environment passively or engage with them in interviews. Also, as design thinkers, we should try to imagine ourselves in these users’ environment, or stepping into their shoes as the saying goes, in order to gain a deeper understanding of their situations. In the following sections, we will outline some methods from d.school Bootcamp Bootleg that will allow you to gain empathy towards your users.

Assuming a Beginner’s Mindset

![]()

Copyright holder: the Author. Copyright terms and license: CC0

The mode dial of a Canon EOS Digital SLR camera. How would a beginner photographer know what to choose? To help beginners, fully automatic modes are represented with icons on the dial, which makes it easy for a non-expert to guess what they mean (e.g., clockwise from top, video, night portrait, sports, closeups, etc.). Icons are also universal – i.e., independent of language. More advanced (expert) modes are shown with abbreviations – you really need to read the manual before you use any of these (e.g., “Tv” doesn’t mean “television”, but “time value” – i.e., shutter priority)! You could only imagine how much confusion this must cause to novice Canon users. Nikon use single letters instead for the advanced modes.

If we are to empathize with users, we should always try to adopt the mindset of a beginner. What this means is that, as designers (or design thinkers), we should always do our best to leave our own assumptions and experiences behind when making observations. Our life experiences create assumptions within us, which we use to explain and make sense of the world around us. However, this very process affects our ability to empathize in a real way with the people we observe. Since completely letting go of our assumptions is impossible (regardless of how much of a checkered reputation the word “assumption” has!), we should constantly and consciously remind ourselves to assume a beginner’s mindset. It’s helpful if you always remind yourself never to judge what you observe, but to question everything—even if you think you know the answer—and to really listen to what others are saying.

Ask What? How? Why?

![]()

Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

UX designers’ attitudes towards their work stem from natural curiosity, inquisitive behavior and constant critical appraisal of everything they encounter. Looking for the underlying factors and motives that drive users’ behaviors and needs is what leads to successful design.

By asking the three questions — What? How? Why? — we can move from concrete observations that are free from assumptions to more abstract motivations driving the actions we have observed. During our observations, for instance, we might find separately recording the “Whats”, “Hows” and “Whys” of a person’s single observation helpful.

In “What”, we record the details (not assumptions) of what has happened. In “How”, we analyze how the person is doing what he/she is doing (is he/she exerting a lot of effort? Is that individual smiling or frowning?). Finally, in “Why”, we make educated guesses regarding the person’s motivations and emotions. These motivations we can then test with users.

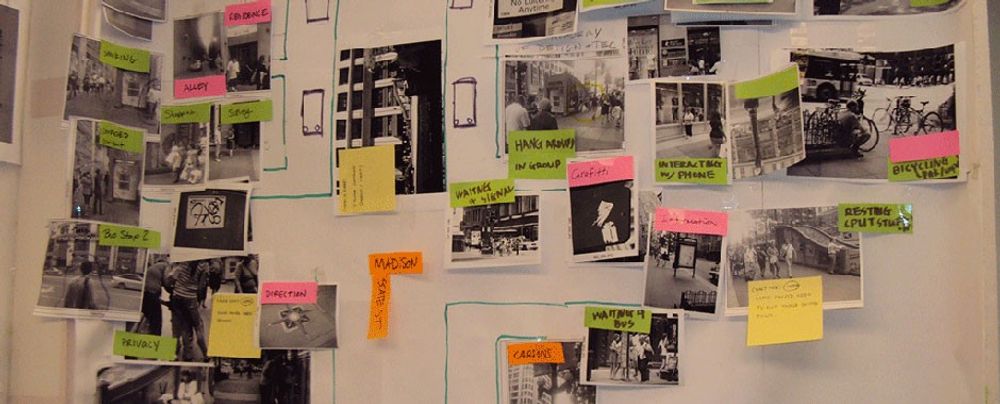

Photo and Video User-based Studies

Photographing or recording target users, like other empathizing methods, can help you uncover needs that people have which they may or may not be aware of. It can help guide your innovation efforts, identify the right end users to design for, and discover emotions that guide behaviors.

In user camera-based studies, users are photographed or filmed either: (a) in a natural setting; or (b) during sessions with the design team or consultants you’ve hired to gather information. For example, you might identify a group of people who possess certain characteristics that are representative of your target audience. You record them while they’re experiencing the problem you’re aiming to solve. You can refresh your memory at a later time with things people said, feelings that were evoked, and behaviors that you identified. You can then easily share this with the rest of your team.

![]()

Copyright holder: NJM2010, Wikimedia. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-SA 3.0

A group of three tourists, trying to find their way in a city. In this, the researchers’ photo, they are huddled around the map shown on the mobile phone. In the photo, we see how hard a time people have when they try to collaborate using the small screen – the girl in the background, for example, has no way of pointing at things on the screen, and hence can’t help her group as much (photo courtesy of A. Komninos, from Besharat et al. 2016).

Personal Photo and Video Journals

In this method, you hand over the camera to your users and give them instructions, namely to take pictures of or video-record their activities during a specified period. The advantage is that you don’t interfere or disturb the users with your personal presence, even though they will adapt and change their normal behavior slightly as they know that you’ll watch the video or see the photo journal later. In a similar way to using personas, by engaging real people, as designers we gain invaluable personal experiences and stories that keep the human aspect of design firmly in mind throughout the whole process. While we probably know, deep down, what limits are involved when three people are trying to use one phone, there’s nothing like the first-hand evidence of a live (and recorded) performance to put this front and center in our awareness from the outset.

![]()

Copyright holder: Andreas Komninos, University of Strathclyde. Copyright terms and license: CC0

Photographs returned by users during a study where they were asked to record cases where they needed to enter text on their mobile or tablet devices. Because the context of use is clearly shown in the pictures, the researchers can understand a lot about where and how text needs to be entered when the returned pictures are good (e.g., in the left image, the user needed to enter a number to pay for parking via mobile, and we can see how much text needed to be entered, the device and even the weather). But not all returned pictures are great! Users are not expert photographers, and they will often return material that isn’t of much use (e.g., on the right, we can see the user is sitting comfortably with their tablet, but we have no idea what they were trying to do, because of the camera flash). Images courtesy of A. Komninos, M.D. Dunlop and E. Nicol, University of Strathclyde.

With that in mind, let’s hear from IDEO, a leading international design consulting firm founded in California in 1991:

“We use this method to go beyond an in-person Interview to better understand a person’s context, the people who surround them, community dynamics, and the journey through how they use a product or service. Photojournals can help create a foundation for richer discussion as they prime an individual before an interview which means they start thinking about the subject a few days in advance.”

– IDEO, Designkit.org, Photojournal

Interviews

![]()

Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Interviews are an important part of the UX designer’s skillset for empathizing with users. However, an interview will yield only minimal results if you are not prepared to conduct it with genuine empathy.

One-on-one interviews can be a productive way to connect with real people and gain insights. Talking directly to the people you’re designing for may be the best way to understand needs, hopes, desires and goals. The benefits are similar to video- and camera-based studies, but interviews are generally structured, and interviewers will typically have a set of questions they wish to ask their interviewees. Interviews, therefore, offer the personal intimacy and directness of other observation methods, while allowing the design team to target specific areas of information to direct the Design Thinking process.

Most of the work happens before the interviews: team members will brainstorm to generate questions to ask users and create themes or topics around the interview questions so they can flow smoothly from one to another.

Engaging with Extreme Users

![]()

Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Extreme users are few in number, but it doesn’t mean you should disregard them and aim just for the main bulk of users instead. In fact, they can provide excellent insights that other users may simply be unprepared to disclose.

By focusing on the extremes, you will find that the problems, needs and methods of solving problems become magnified. First, you must identify the extremes of your potential user base; then, you should engage with this group to establish their feelings, thoughts and behaviors, and then look at the needs you might find in all users. Consider what makes a user extreme and you’ll tend to notice it’s the circumstances involved. A basic example is a grocery store shopping cart and a shopper with five very young children in tow – there are two fold-down seats in the cart, but the other kids (who are also too young to walk) must go somewhere. Our shopper is, therefore, an extreme user of the shopping cart design.

On the one hand, if you can manage to please an extreme user, you should certainly be able to keep your main body of users happy. On the other hand, it is important to note that the purpose of engaging with extreme users is not to develop solutions for those users, but to sieve out problems that mainstream users might have trouble voicing; however, in many cases, the needs of extreme users tend to overlap with the needs of the majority of the population. So, while you may not be able to keep everyone happy at all times with your design, you can certainly improve the chances that it will not frustrate users.

Analogous Empathy

Using analogies can help the design team to develop new insights. By comparing one domain with another, we as designers can conjure different solutions that would not necessarily come to mind when working within the constraints of one discipline. For example, the highly stressful and time-sensitive procedure of operating on a patient in a hospital emergency room might be analogous to the process of refuelling and replacing the tires of a race car in a pit stop. Some of the methods you might use in analogous empathy include comparing your problem and another in a different field, creating an 'inspiration board' with notes and pictures, and focusing on similar aspects between multiple areas.

Sharing Inspiring Stories

![]()

Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

In the words of the great author Terry Pratchett, “People think that stories are shaped by people. In fact, it's the other way around.” We might paraphrase slightly here, as it’s true that products are shaped by the stories that people tell about them.

Each person in a design team will collect different pieces of information, have different thoughts, and come up with different solutions. For this reason, you should share your inspiring stories to collect all of the team members’ research, from field studies, interviews, etc. By sharing the stories that each member has observed, the team can get up to speed on progress, draw meaning from the stories, and capture interesting details of the observation work.

Bodystorming

![]()

Copyright holder: Bank of England, Flickr. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-ND 2.0

A person wearing special goggles that simulate vision impairments, trying to accomplish a simple task (seizing a grain of rice with the tweezers and moving it to the adjacent empty container). Acting out different scenarios can help the researchers themselves better understand the problems that a particular user group might face. This is literally stepping into the users’ shoes!

Bodystorming is the act of physically experiencing a situation in order to immerse oneself fully in the users’ environment. This requires a considerable amount of planning and effort, as the environment must be filled with the artifacts present in the real-world environment, and the general atmosphere/feel must accurately depict the users’ setting. Bodystorming puts the team in the users’ shoes, thereby boosting the feelings of empathy we need as designers in order to come up with the most fitting solutions. Having that ‘real-life’ experience will serve as a reference point for later in the process, enabling us to stop, stand back and ask ourselves: “Remember when we tried being the user? How would this new thing fit in with that?”

The Take Away

When we are in a Design Thinking team, we have a wealth of ways at our disposal to enable us to empathize with our users. Collectively, these methods offer us insight into the users’ needs, and how they think, feel, and behave. Each method attempts to enhance the design team's understanding of their target user and market, and to appreciate exactly what users need and want from their product(s). Observation methods will not only enable us to gather raw data, statistics and demographics; they will also offer opportunities for us to draw insights that we can then apply in designing a solution. Empathizing with users is an essential component of the Design Thinking process; to ignore the benefits of learning from others is to forget what Design Thinking is truly about. Hence, we must, to an appropriate degree, ‘become’ our users if we are to offer them fine-tuned solutions that lead in the market.

References & Where to Learn More

Course: “Design Thinking - The Ultimate Guide”.

d.school Bootcamp Bootleg, 2018.

IDEO.org.

Besharat, J., Komninos, A., Papadimitriou, G., Lagiou, E., & Garofalakis, J. (2016). Augmented paper maps: Design of POI markers and effects on group navigation. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Smart Environments, 8(5), 515-530.