Sympathetic bonding occurs when we perceive someone else’s emotional reaction to be similar to our own experiences. As such, we feel sympathy for that person. It should be obvious that when we are sympathetic to people, we’re more likely to do the things they do and even—to some extent—do the things they want us to do. How do you create such sympathy online when you’re not in the room to be able to create such a bond? Let’s take a look and see how to weave this all-important dynamic into your designs.

What’s Your Favourite Story?

We’d like you to think about your favourite story. Why is it your favourite? Is it the way it makes you feel? Is it the pictures that spring up in your imagination? Is it because it makes you laugh or cry? Is it because of a particular character’s actions?

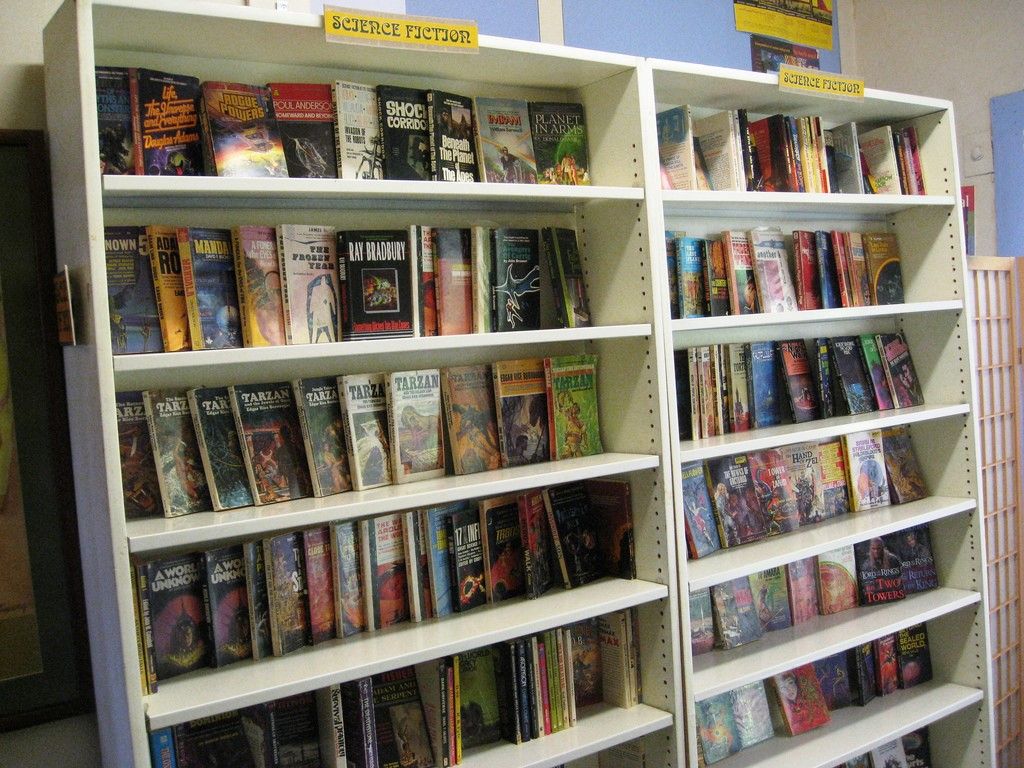

Author/Copyright holder: brewbooks. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

Books and stories go hand in hand. Almost all of our favourite stories originate in books.

There’s a lot going on in a story

Stories don’t just access a small part of our brains. The best stories can tap into all areas of our brains; even the old brain, which relies on providing instinctive decisions. If you’re not convinced that you can tap into the old brain, have you ever read a story so creepy that the hairs stood up on your neck or arms? That’s the old brain at work, processing your fear even though you know it’s only a story. Feeling scared feels pretty good, after all—and it’s certainly worth a trip to the library, an $8 paperback or a $5 Kindle download; it’s certainly an integral part of being human. Not for nothing was horror one of the first genres to crop up in cinema in the 1890s. Similarly, as children, what’s one chief component of the fairytales we hear or read? Horror—encompassing witches, wicked stepmothers and man-eating giants—in tales accesses our fear response from a very early age.

What goes on in your brain while you read a story?

- Your brain processes the sound of the story (if it’s being told or read to you)

- Your brain processes any visual aspects of the story (the letters on the page or any pictures that accompany it)

- Your brain creates visual aspects of the story (the best stories let you believe that you’re there – that’s the brain creating an image of what’s going on)

- Your brain creates an emotional response to the story (laughter, tears, anger, frustration – there’s no doubt at all that a great story gets you fully involved in the action)

- Your brain may even send a few messages to the old brain (those hairs that stand up on your neck or the dilation of your pupils in shock at certain points of the story)

Author/Copyright holder: Ildar Sagdejev. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

When our brains encounter a scary story, they can trigger goose pimples and hair standing up on end.

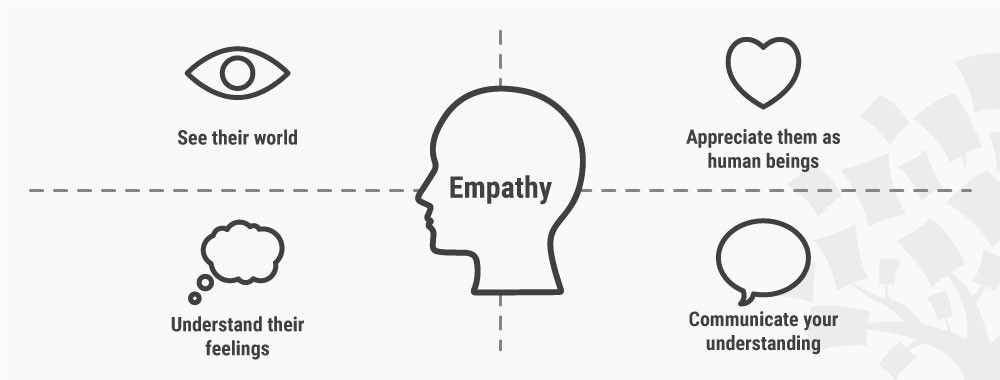

Sympathy and Empathy

The absolute best stories enable you to feel what the lead character or characters feel. In 2004, German social neuroscientist Tania Singer conducted some research to prove this point. Firstly, she hooked some people up to MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) equipment and looked at what happened when the body feels pain. She found that two areas of our brains are devoted to dealing with pain.

The first area deals with where the pain comes from and how intense that pain is. The second has a more subtle function; it decides how we experience that pain, or determines how unpleasant that pain is to us.

After discovering this, she took her experiment to another level, and this is where stories come back into the experiment. She asked some participants to read stories, during which the characters experienced some form of pain. She ran some MRI scans of their brains. What do you think happened?

It turns out that the first area of the brain—the one responsible for determining where our pain comes from and how intense it is—was dormant during the reading. After all, the person reading the story wasn’t in any pain, at least not in the direct sense of the term. So, the brain had no input to respond to.

However, the second area of the brain did respond. The volunteers were processing how bad the pain was, but they were not processing (i.e., experiencing) the pain itself.

It’s not quite the same as experiencing exactly what the character was going through in the story, but it is close enough. It also explains why we feel sympathy or empathy for people in stories. Our brains try to keep us as in touch as possible with the way the character feels. That’s important for social bonding in real-life situations, and it also works online.

Author/Copyright holder: Infrogmation. Copyright terms and licence: Public Domain.

Seeing people in pain or hearing about their pain can make us feel pain, too.

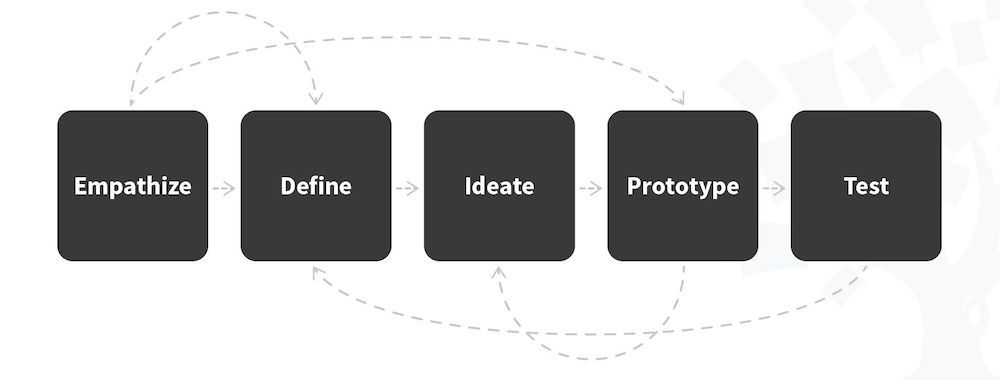

How Could I Use this in Design?

You can use storytelling to tell stories which evoke both sympathy and empathy in the reader (who will be your user or your customer or both). If those reading the story feel sympathy or empathy with the characters in that story, the readers will be more likely to react favourably to your website and your content, and to take action based on that sympathy/empathy.

In the same way as a “story” can refer to a real-life account (such as someone’s life story), it’s important that you realize that when we use the word “character” here, your characters don’t have to be works of fiction. “Character” can refer to you or your team members. Stories don’t have to be made up. They can relate what happens in the real world.

The Take Away

Numerous researchers have proven that stories can evoke both sympathy and empathy in the recipient of the story. Emotional responses to events that befall characters in stories get triggered in the reader in such a way that readers process the degree of the character’s suffering. This makes for a useful point in a design context, because you can tell stories to create a sympathetic bond between you and your users and customers. Your stories do not have to be fictional; you can base them on real-life situations, as long as they are something the audience can relate to. Here again, consider your target audience; fine-tuning this general human response to them will translate to far better chances of your making conversions from your usership.

References & Where to Learn More

Singer T, “Empathy for Pain Involves the Affective but not Sensory Components of the Brain”, Science 20 Feb 2004, Vol 303, 1157-1162

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Ayacop. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.5