Imagine trying to describe everything your product needs to do, without getting lost in technical detail or endless feature lists. That’s the problem Ivar Jacobson set out to solve in the 1980s when he introduced use cases. Instead of worrying about how a system worked internally, he described it from the outside, as if it were a “black box,” focusing on what it does for the people and systems that interact with it. This enabled developers to capture requirements more clearly and consistently, paving the way for the stories of use we rely on today.

In this video, William Hudson, User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd, introduces use cases and explains how Ivar Jacobson created them to bridge requirements to implementation.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

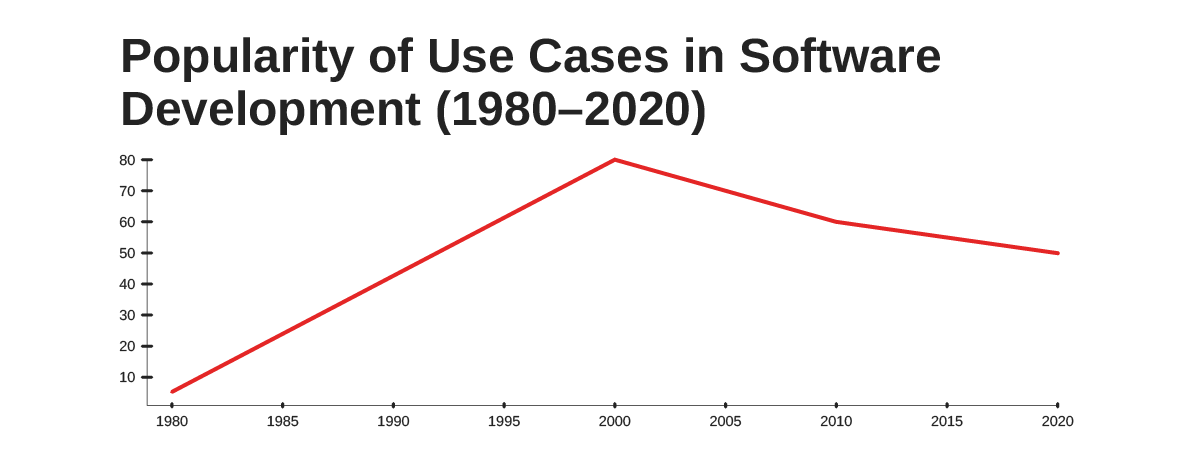

Ivar's original term for use case was the Swedish word användningsfall, which is literally translated as “usage case.” However, this was an awkward phrase in English, so he shortened it to “use case.” The software development community rapidly adopted his approach, and it became the dominant method of specifying a system until Agile became popular around the turn of the millennium (as you can see in the chart at the top).

Diagrams and Narratives: The Two Parts of a Use Case

Use cases come in two parts:

Use case diagrams: An overview of the actors and the use cases they're associated with.

Use case narratives: A description of the interaction between actors and the system for each use case.

In this video, William shows the two parts and explains how the diagrams became part of the Unified Modeling Language (UML).

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

Use Case Diagrams

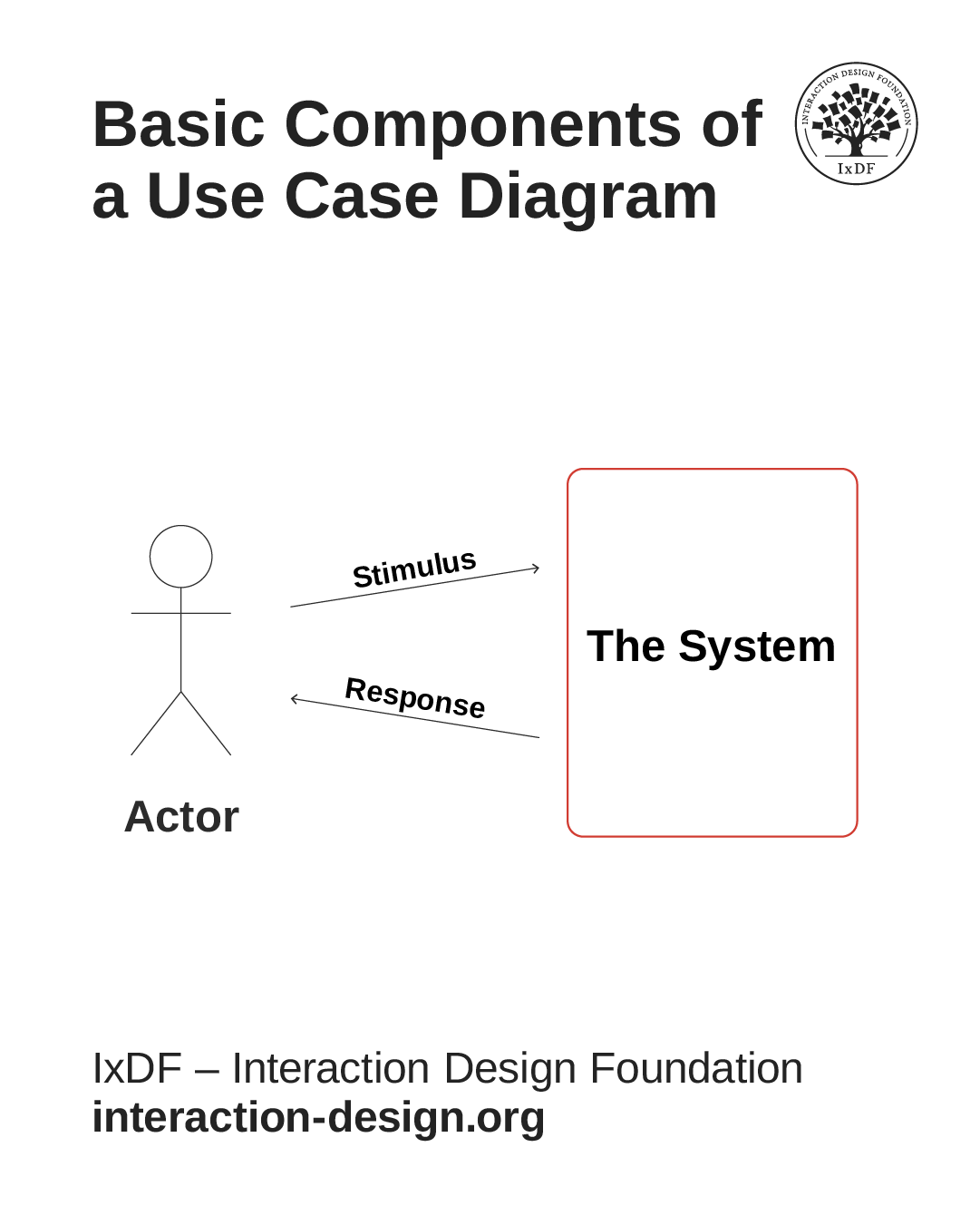

Below is the basic concept of a use case, as shown in the video. Note that the Actor is anything that interacts with the system, including other systems. Actors take roles. Unfortunately, in traditional software development, roles aren't user-centered. They tell us little about the needs and behaviors of the people performing them. In interactive systems, we see uninformative roles like Customer, Manager, or User. But you’re here to fix that!

The basic components of a use case diagram are the Actor, the Stimulus & Response, and the System.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

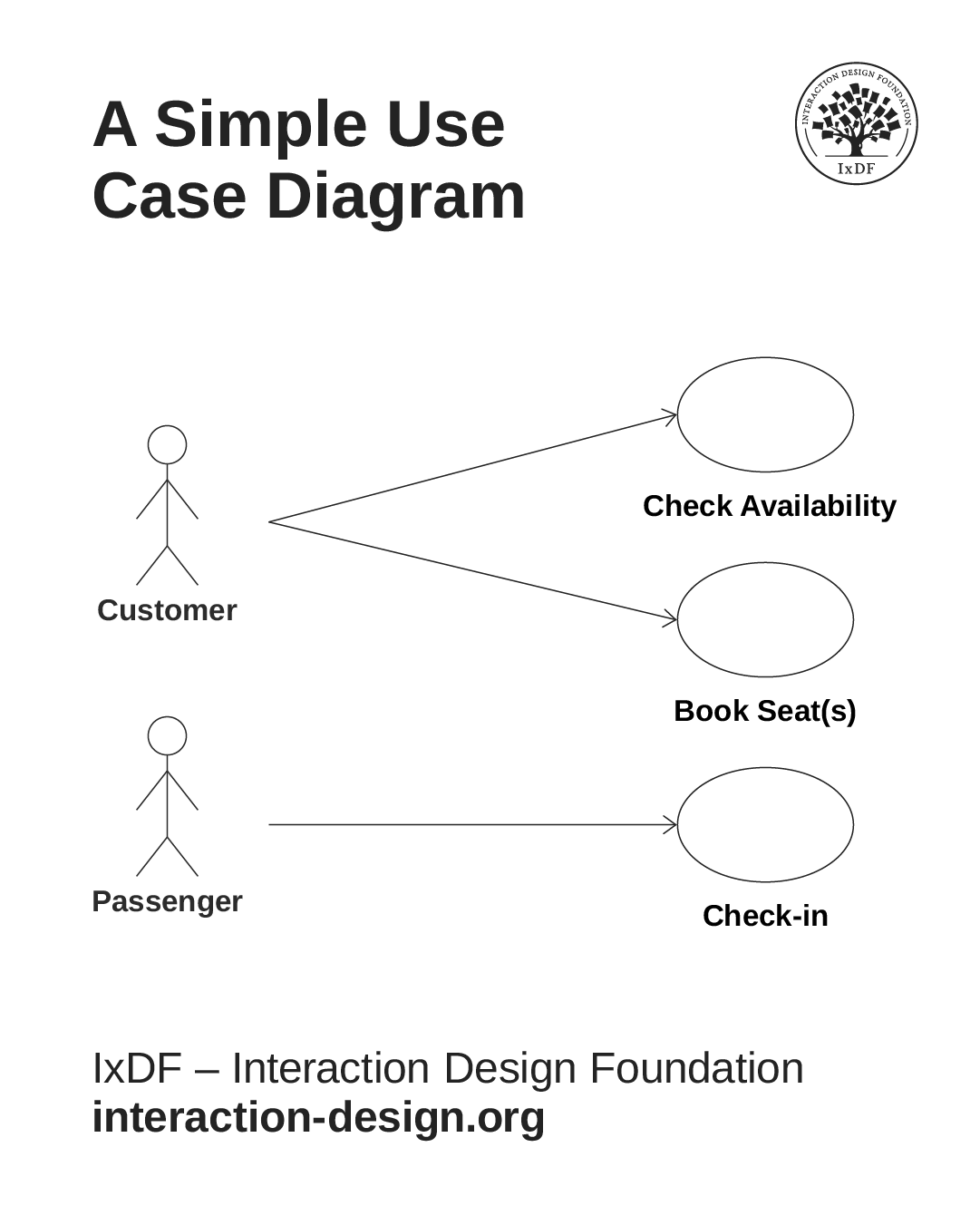

The diagrams are very useful for providing an overall summary of what a system does. However, they contain no element of time or sequence, which can be a drawback. It's common practice to place earlier or more common use cases toward the top of the diagram. This is the case in the sample you saw in the video:

This simple use case diagram shows how the customer and passenger roles interact with a flight booking platform. By convention, time flows down the page, but this isn’t always the case.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Although roles tell us little about users’ needs, they can be important. In the above example, one person may be acting in two distinct roles, or the roles may be taken by different people. It’s an important difference when it comes to boarding a flight.

Use Case Narratives

There's no standard format for use case narratives, but Jacobson specifies the following elements:

Name: A descriptive name for the use case.

Actors: The entities (users or other systems) interacting with the system.

Goal: What the actor is trying to achieve through this interaction.

Pre-conditions: Any conditions that must be true before the use case can be initiated.

Basic Flow: The typical sequence of interactions between the actor and the system.

Alternative Flows: Variations on the basic flow, covering exceptions and other possibilities.

Post-conditions: The state of the system after the use case has been completed.

Here's a simple example:

Name: Reserve Seat Online

Actors: Passenger; Booking Platform

Goal: Select and reserve a seat on an existing flight booking.

Basic Flow:

Passenger logs into the booking platform and opens their reservation.

System displays the flight details and available seats.

Passenger selects a preferred seat.

System updates the reservation with the seat assignment.

System confirms the reservation update.

Alternative Flow: Selected seat unavailable—System notifies the passenger and asks them to choose another seat.

If you're not a programmer, the pre- and post-conditions may sound scary. But they're just the things that must be true for the use case to succeed (pre-conditions) and that must be true once the use case has completed (post-conditions). These are useful for user-centered design and user experience since you may need to display conditions to users before and after the interaction. Consider the pre- and post-conditions for the example above:

Pre-conditions

Passenger must have one or more seats booked on the specified flight.

The flight must be open to online seat booking.

There must be bookable seats available.

Post-conditions

The selected seat(s) are reserved.

The customer is sent a confirmation email for the reservations.

While the above example is simplified, the basic and alternative flow narratives would actually be lengthy. There's also the question of whether passengers should be allowed to reserve seats that the customer purchased if they're different people. An Agile approach to questions like this would leave it to the last minute, called "just-in-time design," but a lot of effort and confusion would be avoided if it were an early design decision.

Match the Detail in Your Stories of Use to the Stage of the Process

One final point about all stories of use, including use cases, is that the appropriate level of detail varies according to where you are in the process. In the early stages of design, stories of use shouldn't include detailed interactions, such as those with interface components. So, you should write “Sandra provides the outbound date for her journey” rather than “Sandra selects the outbound date for her journey from a pop-up calendar.” You can call going into implementation detail too early, “premature design.” While implementation details will be necessary in later stages, they'll distract and limit you if you do them too early. Also, if you provide working prototypes, you’ll often find it more effective than describing interaction details in prose.

The Take Away

Use cases marked an important step in how designers and developers began to capture what a system should do. They made it possible to describe system behavior in a structured way, even if they weren’t always grounded in researched user needs or behaviors.

You’ve now seen how use cases can be expressed both visually, in diagrams, and textually, in narratives. Narratives usually describe the “sunny day” flow, where everything works as expected, but the alternative flows, like the exceptions, decisions, and edge cases, are just as important to capture.

One more lesson from use cases: the right level of detail depends on where you are in the process. Too much detail too early can limit your options and lead to “premature design.” Keep your stories of use at the right level of detail, and you'll stay flexible and creative while still providing structure.

Hero image: © Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0