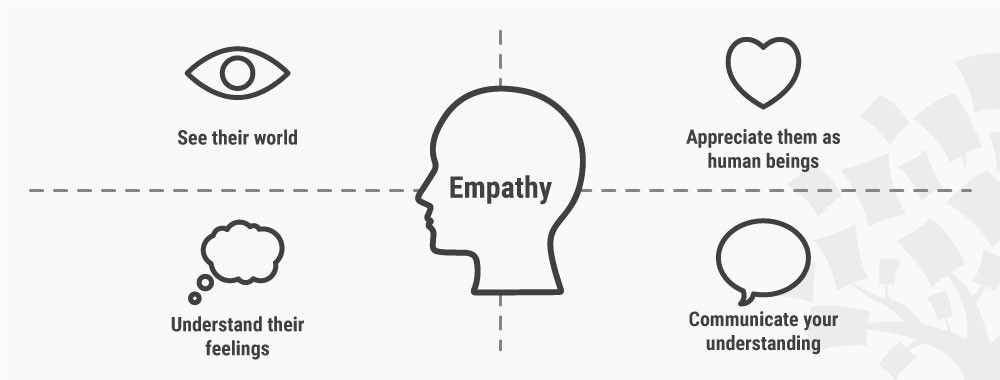

Defining your design challenge is probably one of the most important steps in the Design Thinking process, as it sets the tone and guides all of the activities that follow. In the Define mode, you should end up creating an actionable problem statement which is commonly known as the Point of View (POV) in Design Thinking. You should always base your Point Of View on a deeper understanding of your specific users, their needs and your most essential insights about them. In the Design Thinking process, you will gain those insights from your research and fieldwork in the Empathise mode. Your POV should never contain any specific solution, nor should it contain any indication as to how to fulfill your users’ needs in the service, experience, or product you’re designing. Instead, your POV should provide a wide enough scope for you and your team to start thinking about solutions which go beyond status quo. Here, you’ll also learn to frame and open up your Point Of View, which is the axis that Design Thinking revolves around – a challenge well-framed is half solved.

"Your point of view should be a guiding statement that focuses on specific users, and insights and needs that you uncovered during the empathize mode.

More than simply defining the problem to work on, your point of view is your unique design vision that you crafted based on your discoveries during your empathy work. Understanding the meaningful challenge to address and the insights that you can leverage in your design work is fundamental to creating a successful solution.”

– d.school, Bootcamp Bootleg

Your POV is Your Guide

Your Point of View (POV) defines the RIGHT challenge to address in the following mode in the Design Thinking process, which is the Ideation mode. A good POV will allow you to ideate and solve your design challenge in a goal-oriented manner in which you keep a focus on your users, their needs and your insights about them.

You should construct a narrowly-focused problem statement or POV as this will generate a greater quantity and higher quality solutions when you and your team start generating ideas during later Brainstorm, Brainwriting, SCAMPER and other ideation sessions. In the ideation process, POV will be your guiding statement that focuses on insights and needs of a particular user, or composite character. It’s easy to get lost in the ideations sessions if you don’t have a meaningful and actionable problem statement to help keep your focus on the core essence of your research results from your previous work. A great POV keeps you on track. It helps you design for your users and their needs. If you neglect to define your POV, you may end up getting lost in the ideation processes and in your prototyping process. It’s all too easy to end up focusing on you and your company’s own needs, trying to fulfill your and your company’s own dreams, not to mention the risk of getting lost in creating amazing buttons in the beautiful colours. It’s time to find out how you define your POV.

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

How do you Define your Point Of View?

Step 1

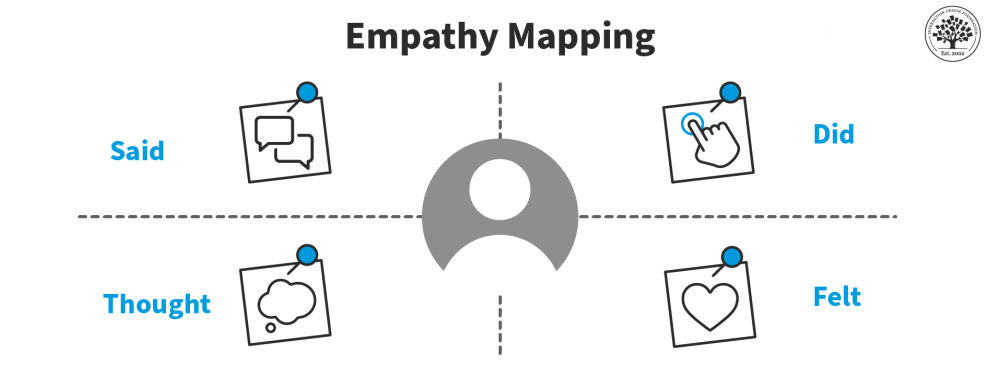

Define the type of person you are designing for – your user. For example, you could define the user by developing one or more personas, by using affinity diagrams, empathy maps and other methods, which help you to understand and crystallise your research results – observations, interviews, fieldwork, etc.

Select the most essential needs, which are the most important to fulfill. Again, extract and synthesise the needs you’ve found in your observations, research, fieldwork, and interviews. Remember that needs should be verbs.

Work to express the insights developed through the synthesis of your gathered information. The insight should typically not be a reason for the need, but rather a synthesised statement that you can leverage in your designing solution.

Step 2

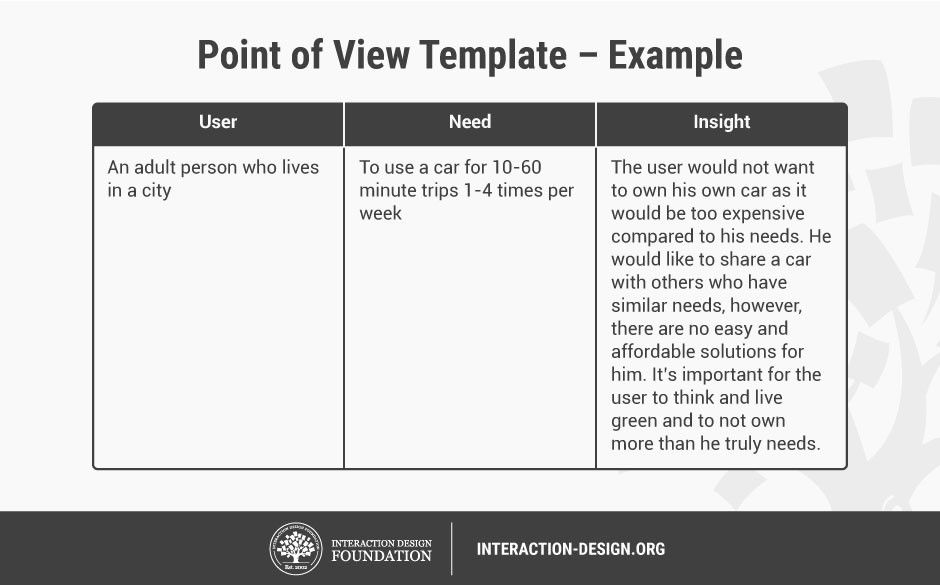

Write your definitions into a Point Of View template like this one:

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Your Point Of View template:

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

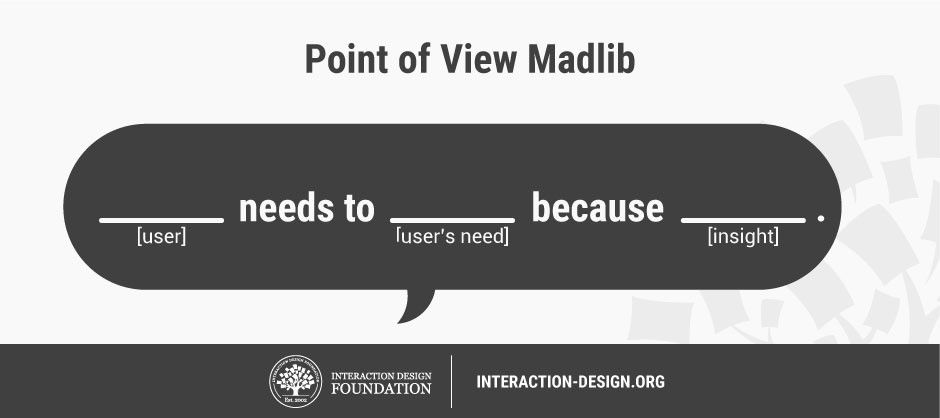

Step 3 – POV Madlib

You can articulate a POV by combining these three elements – user, need, and insight – as an actionable problem statement that will drive the rest of your design work. It’s surprisingly easy when you insert your findings in the POV Madlib below. You can articulate your POV by inserting your information about your user, the needs and your insights in the following sentence:

[User . . . (descriptive)] needs [Need . . . (verb)] because [Insight . . . (compelling)]

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Condense your Point Of View by using this POV Madlib.

Example: An adult person who lives in the city… needs access to a shared car 1-4 times for 10-60 minutes per week … because he would rather share a car with more people as this is cheaper, more environmentally friendly, however, it should still be easy for more people to share.

Author/Copyright holder: Sam Churchill. Copyright terms and license: CC BY 2.0

You articulate a POV by combining these three elements – user, need, and insight – as an actionable problem statement that will drive the rest of your design work. An example could be: “A person who lives in the city… needs access to a shared car 1-4 times for 10-60 minutes per week … he would rather share a car with more people as this is cheaper, more environmentally friendly, and it should still be easy for more people to share.” Here you see one of Google’s driverless cars – a driverless electric car could be a part of the solution to this design challenge. However, at this stage of the design process, we’re not ready to look for solutions just yet.

Step 4 – Make Sure That Your Point Of View is One That:

Provides a narrow focus.

Frames the problem as a problem statement.

Inspires your team.

Guides your innovation efforts.

Informs criteria for evaluating competing ideas.

Is sexy and captures people’s attention.

Is valid, insightful, actionable, unique, narrow, meaningful, and exciting.

Yay! You’re now well-equipped to create a POV and it’s time to understand how to start using your POV which crystallizes all of your previous work in the Empathise mode.

You can download and print the Point Of View template here:

“How Might We” Questions Frame and Open Up Your Design Challenge

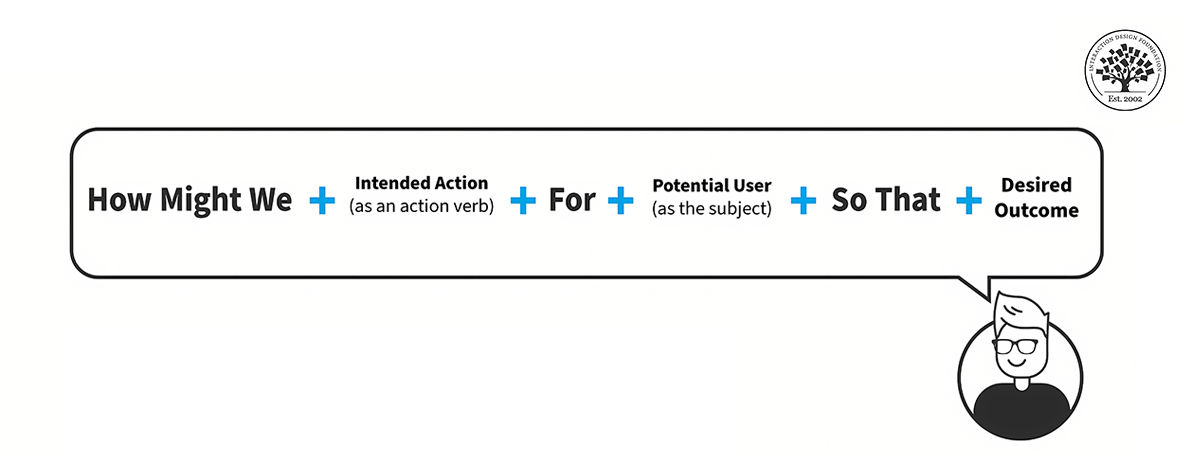

You start using your POV by reframing the POV into a question: Instead of saying, we need to design X or Y, Design Thinking explores new ideas and solutions to a specific design challenge. It’s time to start using the Design Thinking Method where you ask, “How Might We…?”

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

When you’ve defined your design challenge in a POV, you can start opening up for ideas to solve your design challenge. You can start using your POV by asking a specific question starting with, “How-Might-We?” or “in-what-ways-might-we?”. For example: How might we… design a driverless car, which is environmentally friendly, cheap and easy for more people to share?

How Might We (HMW) questions are the best way to open up Brainstorm and other Ideation sessions. HMW opens up to Ideation sessions where you explore ideas that can help you solve your design challenge. By framing your challenge as a How Might We question, you’ll prepare yourself for an innovative solution in the third Design Thinking phase, the Ideation phase. The How Might We method is constructed in such a way that it opens the field for new ideas, admits that we do not currently know the answer, and encourages a collaborative approach to solving it.

For example, if your POV is:

“Teenage girls need… to eat nutritious food… in order to thrive and grow in a healthy way.“

The HMW question may go as follows:

How Might We make healthy eating appealing to young females?

How Might We inspire teenage girls towards healthier eating options?

How Might We make healthy eating something, which teenage girls aspire towards?

How Might We make nutritious food more affordable?

These are simple examples, all with their own subtle nuances that may influence slightly different approaches in the ideation phases. Your HMW questions will ensure that your upcoming creative ideation and design activities are informed with one or more HMW questions, which spark your imagination and aligns well with the core insights and user needs that you’ve uncovered.

“We use the How Might We format because it suggests that a solution is possible and because they offer you the chance to answer them in a variety of ways. A properly framed How Might We doesn’t suggest a particular solution, but gives you the perfect frame for innovative thinking.”

– Ideo.org

How Might We?

The How Might We question purposely maintains a level of ambiguity, and opens up the exploration space to a range of possibilities. It's a re-wording of the core need, which you have uncovered through a deeper interrogation of the problem in your research phase, the Empathise mode in Design Thinking – and synthesized in the Define mode in Design Thinking.

"How" suggests that we do not yet have the answer. “How” helps us set aside prescriptive briefs. “How” helps us explore a variety of endeavors instead of merely executing on what we “think” the solution should be.

"Might" emphasizes that our responses may only be possible solutions, not the only solution. “Might” also allows for the exploration of multiple possible solutions, not settling for the first that comes to mind.

"We" immediately brings in the element of a collaborative effort. “We” suggests that the idea for the solution lies in our collective teamwork.

Without a statement of a clear vision or goal, “How Might We” is obviously meaningless. The words require a well-framed objective, a POV, which is neither too narrow so as to make it overly restrictive, nor too broad so as to leave you wandering forever in infinite possibilities.

An Inspiring HMW example

David and Tom Kelley's book Creative Confidence has the story of the Embrace Warmer, a design challenge undertaken by Stanford Graduate Students aimed at solving the problem of neonatal hypothermia, which costs the lives of thousands of infants in developing countries every year. Faced with the situation where hospital incubators were too expensive as well as physically inaccessible to villagers who lived in rural settings, a team of students engaged in some Empathy research, which led them to formulate the HMW statement:

"How Might We create a baby warming device that helps parents in remote villages give their dying infants a chance to survive?"

This HMW question inspired the design of the Embrace Warmer sleeping bag device, which provides the warmth premature babies in rural villages need, and which they are able to access at a fraction of the cost of traditional hospital incubators.

Whilst a traditional approach may have resulted in technological attempts to reduce the cost of the incubator, empathic research revealed that one of the core issues was the inability or unwillingness of mothers to leave their villages or leave their babies at hospitals for extended periods. This resulted in the reframing of an incubator to a warming device.

Author/Copyright holder: Embrace Innovations. Copyright terms and license: Fair Use.

Author/Copyright holder: Embrace Innovations. Copyright terms and license: Fair Use.

Expand on Your How Might We Questions

Marty Neumeier's Second Rule of Geniusis all about framing and opening up your Point Of View by helping us dream of wishing for what we want. To start wishing, ask yourself the kinds of questions that begin with:

How might we...? (This is the commonly structured framing phrase used to express the essence of the challenge at hand.)

In What Ways Might We…. (Expand on HMW to add the possibility of multiple ways.)

What's stopping us from...?

In what ways could we...?

What would happen if...?

From there, you can ask follow-up questions such as:

Why would we...?

What has changed to allow us to...?

Who would need to...?

When should we...?

“When you let your mind wander across the blank page of possibilities, all constraints and preconceptions disappear, leaving only the trace of a barely glimpsed dream, the merest hint of a sketch of an idea.”

– Marty Neumeier's Second Rule of Genius

Best Practice Guide to Asking How Might We

Begin with your Point of View (POV) or problem statement. Start by rephrasing and framing your Point Of View as several questions by adding “How might we” at the beginning.

Break that larger POV challenge up into smaller actionable and meaningful questions. Five to ten How Might We questions for one POV is a good starting point.

It is often helpful to brainstorm the HMW questions before the solutions brainstorm.

Look at your How Might We questions and ask yourself if they allow for a variety of solutions. If they don’t, broaden them. Your How Might We questions should generate a number of possible answers and will become a launchpad for your Ideation Sessions, such as Brainstorms.

If your How Might We questions are too broad, narrow them down. You should aim for a narrow enough frame to let you know where to start your Brainstorm, but at the same time, you should also aim for enough breadth to give you room to explore wild ideas.

You can download and print out our How Might We template which you and your team can use as a guide:

A Good POV will Make Your Problem Statement Human-Centred

Creating your POV will help you to define the problem as a problem statement in a human-centered manner. A human-centered problem statement is important in a Design Thinking project because it guides you and your team, and focuses on the uncovered specific needs. It also creates a sense of possibility and optimism in that it encourages team members to generate ideas during the Ideation stage, the third and next stage in the Design Thinking process. A good problem statement should thus have the following traits. It should be:

Human-centred. This means you frame your problem statement according to specific users, their needs and the insights that your team has gained during the Empathise phase. Rather than focus on technology, monetary returns or product specifications, the problem statement should be about the people the team is trying to help.

Broad enough for creative freedom. This means the problem statement should not focus too narrowly on a specific method regarding the implementation of the solution. Neither should the problem statement list technical requirements, as these would unnecessarily restrict the team and prevent them from exploring areas that might bring unexpected value and insight to the project.

Narrow enough to make it manageable. On the other hand, a problem statement such as “Improve the human condition” is too broad and will likely cause team members to feel easily daunted. Problem statements should have sufficient constraints to make them manageable.

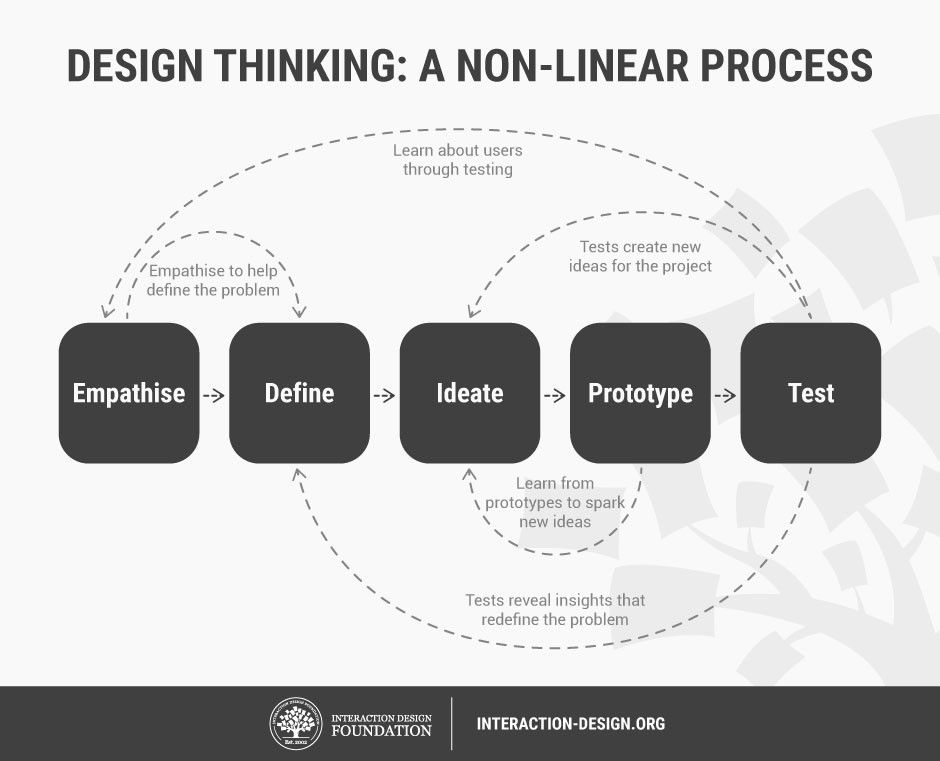

Linear Problem Solving vs. the Non-Linear Nature of Design Thinking

This design challenge framing is in stark contrast to the business models for linear problem solving, which rationally attempt to define everything upfront, and then etch away at achieving the set solution systematically. Design Thinking is also very systematic, but its approach is more about uncovering the problem rather than etching away at a set solution. Idris Mootee mentions in his book, Design Thinking for Strategic Innovation, that more than 80% of management tools, systems, and techniques are for value capture, but that the role of Design Thinking is for value creation.

Well-framed Challenges

A well-framed challenge has just enough constraints, with space to explore. You might have encountered the following linear problem-solving approach by your manager telling you: "Design a poster which increases sign-ups to our next event."—or—"Redesign the packaging so our product is more noticeable on the shelf." These kinds of briefs quite often attempt to solve the problem of target markets not responding well enough to what's on offer, and are attempts to put a patch on things. Design Thinking digs deeper and helps us understand the users, their needs and our insights about them before we decide upon which course of action to take. As such, Design Thinking will instead help us ask and research: “Why are people not signing up for the event?” and “What is it about our product that causes people to ignore it?”

Design Thinking helps us focus on what kind of userswe’re dealing with, their needs we're trying to address in our design challenge, and then understand whether we're actually addressing those needs well enough.

Define and re-define – The Non-Linear Nature of Design Thinking

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

The five stages of Design Thinking are not sequential steps, but different “modes” you can put yourself in, to iterate on your problem definition, ideas, or prototype, or to learn more about your users at any point during the project. It is important to be aware from the outset that the initial definition of your challenge is based upon your initial set of constraints or understandings, and that you should revisit and re-frame your definition often as you uncover new insights indicating a problem in the framing as you work in the other four Design Thinking modes.

Know Your History

One of the most commonly structured framing phrases which we use to express the essence of the challenge at hand is: How Might We? (HMW). The Phrase is rumoured to have been popularized by Min Basadur at Proctor and Gamble, then on to IDEO, next at Google and later at Facebook in a viral breakout, that has since revolutionised how companies frame their innovation challenges. GK Van Platter of Humantific references a much earlier example in an article entitled, Origins of How Might We? (2012). The reframing technique has its roots all the way back in the mid-sixties, with a work by Sidney J. Parnes Ph.D "Creative Behavior Guidebook", which touches on the concept of "Invitation Stems" or "How Mights" .

The Take Away

Spend enough time to carefully consider the format and composition of your POV and HMW questions to ensure that your upcoming creative ideation and design activities are informed with one of more HMW questions, which spark your imagination and align well with the core insights and user needs that you’ve uncovered. Creating your POV helps you define your problem statement in a human-centred manner.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

– Albert Einstein

References & Where to Learn More

Idris Mootee, Design Thinking for Strategic Innovation: What They Can't Teach You at Business or Design School, 2013

Ideo.org, How Might We.

Marty Neumeier, The Rules of Genius #2, Wish for what you want, 2014.

Sarah Soule: How Design Thinking Can Help Social Entrepreneurs, 2013.

Warren Berger, The Secret Phrase Top Innovators Use, 2012.

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Simon Powell. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0