Loss Aversion Theory - The Economics of Design

- 738 shares

- 9 years ago

Behavioral economics is a discipline that examines how emotional, social and other factors affect human decision-making, which is not always rational. As users do not always have stable preferences or act in their best interests, designers can guide their decisions via strategic choice architecture—e.g., pricing structure.

See how a grasp of behavioral economics can help drive effective interventions in the following video by Big Think.

“Choose less and feel better.”

— Barry Schwartz, Psychologist and author

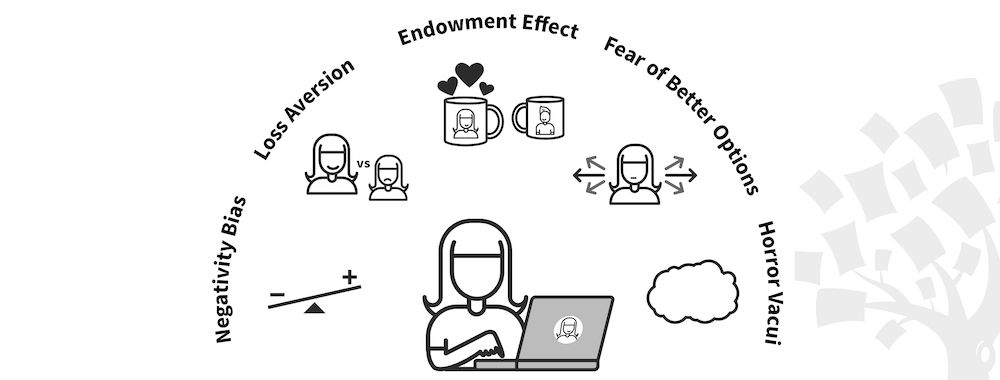

Before 20th-century advances in psychology and neuroscience, human thinking was typically deemed a rational process of analyzing situations logically to find optimal solutions. Behavioral economics turns that idea around and proves that humans can’t weigh up pros and cons so clinically. Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky pioneered the field in the 1970s, isolating “cognitive illusions” that affect judgment and determining the human tendency to make irrational choices in the face of uncertainty. They found the potential value of losses and gains—not rational assessments of outcome—guides decision-making. This school of thought asserts the pain of loss is far more profound than the pleasure of gaining something equally valuable. Human thinking is naturally bounded by limitations in knowledge, processing ability and feedback; thus, designers should consider users’ aversion to thinking too much and frame selected options insightfully.

Fundamental to behavioral economics is that two thought systems are at work in people—one operates with intuitive, experience-based and relatively unconscious processes; the other involves controlled analytical processes and depends on a person’s cognitive ability, in-the-moment bias and influence from society. Using behavioral economics principles, designers present the right information (and right amount) to engage users and guide them towards desired calls to action.

In user experience design, designers exploit a uniquely human fact—the brain is naturally a cognitive miser. It doesn’t like being flooded with information; so, the power of choice can be a strain. Complex decisions are taxing, even if users can take their time. Regardless of intelligence, they’ll seek simpler solutions and will subconsciously apply heuristics (judgmental shortcuts) to minimize effort. However rational users believe they are, they can be prompted to act in ways they might never expect. A common example is to leverage how people consider an item’s value in relative—not absolute—terms and lead them to buy a high-value product because it seems like a bargain compared with costlier ones.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

When accessing unfamiliar content such as new interfaces, users will base decisions on value judgments and context. Therefore, to help users make choices that benefit themselves and the business, you should make your designs easier to understand and navigate while carefully considering the ethical dimensions. The best design solutions always work in the users’ and provider’s best interests. A vital distinction is the difference between manipulating users and ethically applying principles of behavioral economics. Reputable e-commerce solutions exemplify the latter, including:

Framing—Drop the right anchor to set a frame of reference. Anchoring is a form of priming where the first number users see serves as a marker for judging other items’ values. As this first piece of information impacts users’ decision-making, you can prompt them to compare other offerings favorably against it by highlighting a more expensive item.

Defaulting—Give users the right defaults to help them decide what to do/buy. Limit choices to only those most appropriate for the step/category; typically, if you show users more than 4 options, they’ll start feeling overwhelmed. Regarding an item’s extra features, users will prefer a higher-priced baseline (to remove options from) over a lower-priced one (to add options to).

Reciprocation/Power of Free—Offer free items; it’s a guaranteed way to put goods in users’ hands, and it fosters obligations (e.g., “If you liked this article, please share it.”).

Streamlining—Remove obstacles from processes (e.g., Amazon’s one-click ordering feature); similarly, insert obstacles to discourage unwanted behavior, but be careful of dark patterns.

Social proof—Make users feel they’ll be consumers of a popular item, which also usually bolsters their sense of security, as does the power of authority via expert/celebrity endorsement.

Attribute priming—Strategically guide users’ attention toward specific product features or aspects of an experience that you want to emphasize.

Scarcity—Tap into the fear of loss and raise the value of limited items in users’ minds.

Salience—Make a feature or piece of information more noticeable when users make decisions; when it captures their attention more readily, they’ll tend to give it more weight in their decision-making.

Guard-railing—Keep users on track towards desired actions and make course-correction easy.

Tackling Loss Aversion—Word incentives to showcase potential gains and downplay negative outcomes (e.g., a 90% success rate sounds more attractive than a 10% failure rate).

You should present features to simplify the user experience and prevent information overload. Above all, frame options ethically to offer meaningful change through user-centered design and appropriate nudging towards desirable actions for all parties concerned.

WordPress’s home page uses social proof—by highlighting that a whopping 35% of the Internet is built on WordPress, it makes people trust the platform more.

Amazon’s checkout flow uses salience—when you purchase an external hard drive, it presents you with a data recovery add-on before you checkout.

Here’s an in-depth, example-rich article on persuasive design, including behavioral design elements.

This insightful piece explores additional considerations concerning behavioral economics.

Behavioral economics in UX design is the study of how people make decisions—often irrationally—and how designers can use those insights to shape better user experiences. Unlike classical economics, which assumes that individuals act logically, behavioral economics recognizes that users rely on mental shortcuts and biases.

For instance, people tend to avoid losses more than they seek gains—the tendency of loss aversion. The message often becomes more compelling if a UX designer highlights what users lose by not acting (like missing a deadline or deal). Another common effect is the default bias; users tend to stick with preset options, so thoughtful defaults can nudge people toward better or more ethical choices.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Read our piece, Loss Aversion Theory - The Economics of Design for valuable insights.

Behavioral economics helps UX designers understand users by revealing how people make decisions—not how we think they should. It highlights that users often rely on mental shortcuts and biases, like defaulting to preset options or avoiding losses more than seeking gains.

For example, the “default effect” shows that users stick with pre-selected choices. You can tap into this by setting eco-friendly or privacy-conscious options as defaults. Another principle, “loss aversion,” suggests users fear losing something they have more than they value gaining something new. This can inform how we frame choices—emphasizing what users might miss out on can be more persuasive than highlighting benefits.

Applying insights like these, designers can create interfaces that guide users toward better decisions without restricting freedom. For example, the right information, and the right amount of it, presented at the right time can help users of a new app achieve what they want and enjoy the product and the brand behind it. It’s not about manipulation; it’s about designing with human behavior in mind and making experiences more intuitive and effective.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Read our piece, Loss Aversion Theory - The Economics of Design for valuable insights.

Important behavioral economics principles for UX design include:

Loss aversion shows that users feel the pain of loss more than the joy of gain. So, framing messages around what users stand to lose—like missed opportunities or wasted time—can increase engagement.

Default bias means users often stick with preset options. That’s why setting smart defaults—like energy-saving modes or privacy-friendly settings—can lead to better outcomes with zero effort from the user.

Anchoring is where users rely heavily on the first piece of information they see. Showing a higher “original” price next to a discounted one makes the discount feel more substantial. Anchors can also guide users toward premium plans or preferred choices.

The framing effect refers to how the way options appear influences decisions. It’s in the presentation; for example, saying “95% success rate” feels more reassuring than “5% failure rate,” even though they’re logically identical. UX writing and visual layout should frame choices positively or strategically based on context.

The endowment effect, which mirrors aspects of loss aversion, accounts for how people value things more once they feel ownership. Free trials or customization features tap into this bias and make users more likely to commit.

Designers who understand these principles and leverage them ethically can build experiences that feel intuitive, reduce friction, and support users and their brand.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Take our course, Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation for valuable insights.

Nudge theory, from behavioral economics, is the idea that you can influence people’s decisions subtly, without restricting their freedom, by shaping the environment in which they choose. In UX design, a “nudge” gently steers users toward better or more desirable actions while still leaving them in control.

A classic example is the default option. If a newsletter signup box is pre-checked, more users will subscribe, simply because that’s the path of least resistance. However, be mindful of dark patterns, design practices where default settings like prechecked boxes can leave users feeling tricked if the designer isn’t acting in the users’ interest. (Beware that pre-checked boxes violate GDPR in some countries.) Other examples of nudges include progress bars, which can increase task completion by signaling momentum.

Designers use nudges to promote ethical and user-friendly behavior. For example, encouraging energy-saving settings, highlighting socially responsible purchases, or using positive reinforcement (“You’re almost there!”) in onboarding flows.

Used well, nudges improve usability and guide smarter decisions, without manipulation. An ethical approach is always the best one.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Take our course, Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation for valuable insights.

To apply behavioral economics to improve user engagement, design around how people actually think and make decisions—not how they should. Start with loss aversion: frame actions in terms of what users stand to lose if they don’t engage, like “Don’t miss your free trial ending tomorrow.” This taps into users’ natural fear of missing out.

Use the default effect to simplify choices; auto-enroll users in helpful features with the option to opt out—instead of than forcing them to opt in. To build trust and momentum, you can also apply social proof, like showing how many others have completed a task (e.g., “5,000 designers already downloaded this guide”).

Gamification elements, including progress bars, badges, and streaks, leverage behavioral triggers like completion bias, where people feel driven to finish what they’ve started. Similarly, offering value first (like a free download) taps into reciprocity, a user’s instinct to give something back, like signing up or sharing. They can make engagement feel rewarding and purposeful.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Take our course, Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation for valuable insights.

The line between persuasion and manipulation in design lies in intent, transparency, and user benefit. Persuasive design respects user autonomy—it uses behavioral insights to guide, not deceive. For example, highlighting a popular plan nudges users toward it, but still leaves clear, honest choices.

Manipulative design—like dark patterns—crosses the line by hiding options, creating false urgency, or tricking users into actions they wouldn’t otherwise choose. If a user feels regret, frustration, or misled afterward, the design likely veered into manipulation.

Ask yourself: Does this interaction align with the user’s goals? Are all options clear and accessible? Is the benefit mutual?

Ethical persuasion builds trust and long-term engagement. Manipulation might drive short-term metrics, but it damages brand credibility and user loyalty. Aside from the moral question, manipulative approaches can be illegal in many jurisdictions.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Read our article How to Design Ethically: Expert Advice from Guthrie Weinschenk, Behavioral Economist, Attorney and the COO of The Team W, Inc., for important insights.

User research methods that align with behavioral economics focus on what users actually do, not just what they say. So, start with observational research—watch how users interact with your product in real-world settings. This reveals unconscious behaviors and biases that users may not report in interviews.

A/B testing is another key method. It lets you measure how small changes in wording, layout, or defaults affect behavior, helping you validate behavioral nudges like loss framing or social proof in action.

Use field experiments to test decision-making under real conditions. For example, see whether adding a progress bar or changing a call-to-action increases task completion.

Also, conduct usability testing with a behavioral lens—observe hesitations, default selections, or irrational choices to spot where biases influence outcomes.

Watch our video about behavioral economics:

Enjoy our Master Class Behavioral Design: Create Engaging Products with Behavioral Science with Susan Weinschenk, Chief Behavioral Scientist and CEO at The Team W, Inc., and Guthrie Weinschenk, Behavioral Economist, Attorney and the COO of The Team W, Inc.

Lee, M. K., Kiesler, S., & Forlizzi, J. (2011). Mining behavioral economics to design persuasive technology for healthy choices. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 325–334). ACM.

In this study, the authors explore how behavioral economics principles can inform the design of persuasive technologies aimed at promoting healthier choices. They apply strategies such as default options, planning prompts, and asymmetric choices in various contexts, including snack selection and health-related decision-making. The research provides empirical evidence on the effectiveness of these strategies in influencing user behavior. This work is significant for UX designers seeking to incorporate behavioral insights into technology that encourages positive user actions.

Benartzi, S., & Bhargava, S. (2020). How digital design drives user behavior. Harvard Business Review.

Benartzi and Bhargava discuss how digital design elements, informed by behavioral economics, can significantly influence user decisions. They highlight how subtle changes in interface design, such as the framing of choices and the use of defaults, can lead to better user outcomes in areas like retirement savings and health plan selection. The article emphasizes the importance of integrating behavioral insights into UX design to facilitate better decision-making. This piece is influential in bridging the gap between behavioral economics theory and practical UX application.

Wendel, S. (2013). Designing for Behavior Change: Applying Psychology and Behavioral Economics. O’Reilly Media.

Stephen Wendel’s Designing for Behavior Change is a hands-on guide for using behavioral science to craft digital products that influence human behavior ethically and effectively. Wendel, a behavioral economist, outlines a structured process to help designers identify target behaviors, apply psychological principles, and test their impact. The book includes practical design patterns, case studies, and tools tailored to product development teams. It bridges theory and application, making it especially valuable for UX professionals who want to create experiences that are not just engaging but behaviorally sound. This work is central to the growing field of behavioral UX, where insights from economics and psychology drive better design outcomes.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

In this landmark book, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman explores the dual-process theory of the mind—System 1 (fast, automatic thinking) and System 2 (slow, deliberate reasoning). Thinking, Fast and Slow reveals how biases and heuristics distort judgment and decision-making. For UX designers, the implications are profound: understanding how users process information helps in designing more intuitive, accessible, and cognitively aligned interfaces. The book offers a foundation for anticipating user behavior, avoiding cognitive overload, and crafting user-centered solutions. Kahneman’s work has become a cornerstone in both psychology and UX, offering a rigorous framework for predicting and shaping user actions through design.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Nudge: The Final Edition. Penguin Books.

Nudge: The Final Edition by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein expands on their revolutionary concept of “choice architecture”—the idea that small design changes can significantly influence behavior without restricting freedom. This updated version includes fresh insights into digital nudging and real-world policy implementations. For UX designers, Nudge offers practical tools for guiding user decisions in a way that is ethical and user-focused. The authors draw from behavioral economics to demonstrate how people make suboptimal decisions and how better design can help. This book is essential for designers aiming to build experiences that empower users to make smarter, healthier, and more sustainable choices.

Yes; personas and journey maps are powerful tools for applying behavioral insights in UX. First, you’ll want to enrich your personas with behavioral traits, not just demographics or goals. Include biases like “avoids complex decisions” (choice overload) or “prefers defaults” (default effect). This helps you design nudges that match how users think. Many users will dislike complex decisions, so endow your personas with deeper traits to give them more credible substance.

With journey maps, identify decision points where users hesitate, drop off, or choose irrationally. Then apply behavioral cues—like social proof near checkout, or loss framing in cancellation flows—to guide better choices without pressure.

For example, if a user hesitates during sign-up, show a progress bar (completion bias) or highlight how many others joined today (social proof). These nudges align behavioral science with user context, boosting engagement and satisfaction. In any case, take an ethical approach to envisioning your users' journeys; it will help you leverage behavior economics principles in ways that best serve users and your brand.

Watch as William Hudson, User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd, explains why design without personas falls short:

Enjoy our Master Class Behavioral Design: Create Engaging Products with Behavioral Science with Susan Weinschenk, Chief Behavioral Scientist and CEO at The Team W, Inc., and Guthrie Weinschenk, Behavioral Economist, Attorney and the COO of The Team W, Inc.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Behavioral Economics (BE) by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Behavioral Economics (BE) with our course Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation .

Make yourself invaluable with powerful design skills that directly increase adoption, drive business growth, and fast-track your career. Learn how to strategically engage early adopters and achieve critical mass for successful product launches. As AI becomes part of how products are developed, tested, and scaled, you stay in demand when you can design experiences people connect with and choose to return to. These timeless human-centered design skills help you guide AI so faster production still leads to ethical experiences that people can trust and love.

Gain confidence and credibility with bite-sized lessons and practical exercises you can immediately apply at work. Master the Path of Use to understand what drives usage and captivates people. You'll use the economics of design, network effects, and social systems to drive product adoption in any industry. Analyze real-world product launch successes and failures, and learn from others' mistakes so you can avoid costly trial and error. This course will give you the hands-on design skills you need to launch products with greater confidence and success.

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!