As Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and Interaction Design moved from designing and evaluating work-oriented applications towards dealing with leisure-oriented applications, such as games, social computing, art, and tools for creativity, we have had to consider e.g. what constitutes an experience, how to deal with users’ emotions, and understanding aesthetic practices and experiences. Here I will provide a short account of why in particular emotion became one such important strand of work in our field.

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Rikke Friis Dam and Mads Soegaard. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Affective Computing video 1 - Introduction to Affective Computing and Affective Interaction

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Rikke Friis Dam and Mads Soegaard. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Affective Computing video 2 - Main Guidelines and Future Directions

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Rikke Friis Dam and Mads Soegaard. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Affective Computing video 3 - Designing Affective Interaction Products Dealing With Stress

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Rikke Friis Dam and Mads Soegaard. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Affective Computing video 4 - Business value, value, and inspirations

I start by describing the wave of research in a number of different academic disciplines that resurrected emotion as a worthy topic of research. In fact, before then one of the few studies of emotion and emotion expression that did not consider emotion as a problem goes back as far as to Darwin’s “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals” in 1872 (Darwin, 1872). After Darwin, much attention in the academic world was focused on how emotion is problematic to rational thinking.

The new wave of research on emotion spurred ideas both amongst AI-researchers and HCI-researchers. In particular, the work by Rosalind Picard with her book on “Affective Computing” opened a viable research agenda for our field (Picard, 1997). But as with any movement within HCI, there will be different theoretical perspectives on the topic. A counter reaction to Picard’s cognitivistic models of emotion came from the work by Sengers, Gaver, Dourish and myself (Boehner et al 2005,Boehner et al 2007, dePaula and Dourish 2005, Gaver 2009, Höök, 2008, Höök et al., 2008). Rather than pulling on a cognitivistic framework, this strand of work, Affective Interaction, draws upon phenomenology and sees emotion as constructed in interaction – between people and between people and machines.

While the work in these two strands on designing for emotion has contributed a lot of insights, novel applications, and better designs, both have lately come to a more realistic design aim where emotion is just one of the parameters we have to consider. Instead of placing emotion as the central topic in a design process, it is now seen as one component contributing to the overall design goal. In particular, it becomes a crucial consideration as we approach design for various experiences and interactions.

12.1 History: the resurrection of emotion

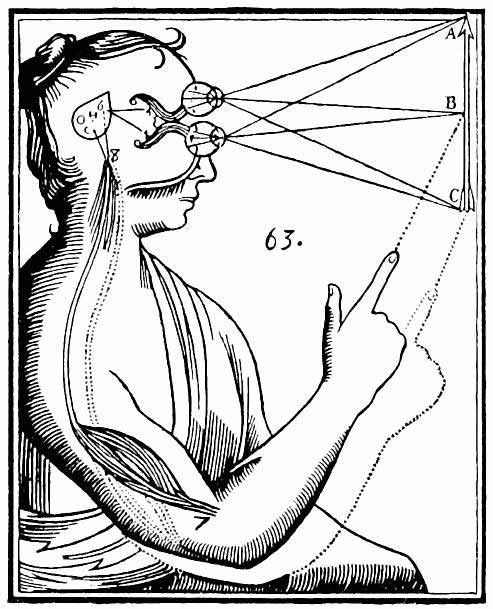

During the 1990ies, there was a wave of new research on the role of emotion in diverse areas such as psychology (e.g. Ellsworth and Scherer, 2003), neurology (e.g. LeDoux, 1996), medicine (e.g. Damasio, 1995), and sociology (e.g. Katz, 1999). Prior to this new wave of research, emotions had, as I mentioned, been considered to be a low-status topic of research, and researchers had mainly focused on how emotion got in the way of our rational thinking. Results at that point focused on issues like when getting really scared, pilots would get tunnel vision and stop being able to notice important changes in the flight’s surroundings. Being upset with a colleague and getting angry in the middle of a business meeting could sabotage the dialogue. Or giving a presentation and becoming very nervous could make you loose the thread of the argument. Overall emotions were seen the less valued pair in the dualistic pair rational – emotional, and associated with body and female in the “mind – body”, “male – female” pairs. This dualistic conceptualisation goes back as far as to the Greek philosophers. In Western thinking, the division of mind and body was taken indisputable and, for example, Descartes looked for the gland that would connect the thoughts (inspired by God) with the actions of the body, Figure 1.

Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 12.1: René Descartes' illustration of dualism. Inputs are passed on by the sensory organs to the epiphysis in the brain and from there to the immaterial spirit.

But with this new wave of research in the 90ies, emotion was resurrected and given a new role. It became clear that emotions were the basis for behaving rationally. Without emotional processes we would not have survived. Being hunted by a predator (or enemy aircraft) requires focusing all our resources on escaping or attacking. Tunnel vision makes sense in that situation. Unless we can associate feelings of uneasiness with dangerous situations, as food we should not be eating, or people that aim to hurt us, we would make the same mistakes over and over, see Figure 2.

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Master Sgt. Lance Cheung. Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 12.2: Focusing on enemy aircraft, getting tunnel vision

While fear and anger may seem as most important to our survival skills, our positive and more complex socially-oriented emotion experiences are also invaluable to our survival. If we do not understand the emotions of others in our group of primates, we cannot keep peace, share food, build alliances and friendships to share what the group can jointly create (Dunbar, 1997). To bring up our kids to function in this complex landscape of social relationships, experiences of shame, guilt, and embarrassment are used to foster their behaviour (Lutz 1986, Lutz 1988). But positive emotions also play an important role in bringing up our kids: conveying how proud we are of our kids, making them feel seen and needed by the adults, and unconditional love.

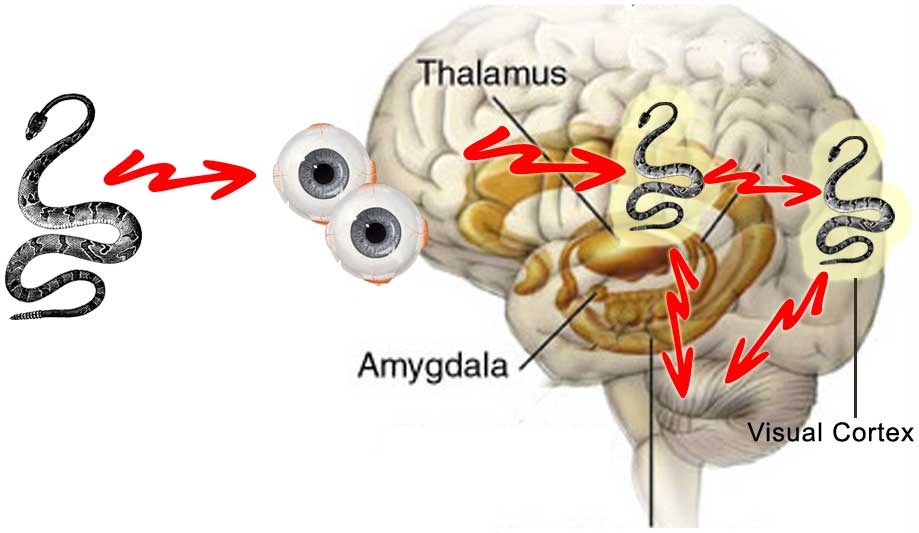

The new wave of research also questioned the old Cartesian dualistic division between mind and body. Emotional experiences are not residing in our minds or brains solely. They are experienced by our whole bodies: in hormone changes in our blood streams, nervous signals to muscles tensing or relaxing, blood rushing to different parts of the body, body postures, movements, facial expressions (Davidson et al., 2002). Our bodily reactions in turn feedback into our minds, creating experiences that regulate our thinking, in turn feeding back into our bodies. In fact, an emotional experience can start through body movements; for example, dancing wildly might make you happy. Neurologists have studied how the brain works and how emotion processes are a key part of cognition. Emotion processes are basically sitting in the middle of most processing going from frontal lobe processing in the brain, via brain stem to body and back (LeDoux, 1996), see Figure 3.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation). See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.3: LeDoux’s model of fear when seeing a snake.

Bodily movements and emotion processes are tightly coupled. As discussed by the philosopher Maxine Sheets-Johnstone in The Corporeal Turn: A interdisciplinary reader, there is “a generative as well as expressive relationship between movement and emotion” (Sheets-Johnstone, 2009). Certain movements will generate emotion processes and vice-versa.

But an emotional experience is not only residing “inside” our bodies as processes going back and forth between different parts of our body, they are also in a sense spread over the social setting we are in (Katz, 1999, Lutz, 1986, Lutz 1988, Parkinson, 1996). Emotions are not (only) hard-wired processes in our brains, but changeable and interesting regulating processes for our social selves. As such, they are constructed in dialogue between ourselves and the culture and social settings we live in. Emotion is a social and dynamic communication mechanism. We learn how and when certain emotions are appropriate, and we learn the appropriate expressions of emotions for different cultures, contexts, and situations. The way we make sense of emotions is a combination of the experiential processes in our bodies and how emotions arise and are expressed in specific situations in the world, in interaction with others, coloured by cultural practices that we have learnt. We are physically affected by the emotional experiences of others. Smiles are contagious.

Catherine Lutz, for example, shows how a particular form of anger, named song by the people on the south Pacific atoll Ifaluk, serves an important socializing role in their society (Lutz, 1986, Lutz 1988). Song is, according to Lutz, “justifiable anger” and is used with kids and with those who are subordinate to you, to teach them appropriate behaviour in e.g. doing your fair share of the communal meal, failing to pay respect to elders, or acting socially inappropriately.

Ethnographic work by Jack Katz (1999) provides us with a rich account of how people individually and group-wise actively produce emotion as part of their social practices. He discusses, for example, how joy and laughter amongst visitors to a funny mirror show is produced and regulated between the friends visiting together. Moving to a new mirror, tentatively chuckling at the reflection, glancing at your friend, who in turn might move closer, might in the end result in ‘real’ laughter when standing together in front of the mirror. Katz also places this production of emotion into a larger complex social and societal setting when he discusses anger among car drivers in Los Angeles, see Figure 4. He shows how anger is produced as a consequence of a loss of embodiment with the car, the road, and the general experience of travelling. He connects the social situation on the road; the lack of communicative possibilities between cars and their drivers; our prejudice of other people’s driving skills related to their cultural background or ethnicity; etc.; and shows how all of it comes together explaining why anger is produced and when, for example, as we are cut off by another car. He even sees anger as a graceful way to regain a sense of embodiment.

Copyright terms and licence: pd (Public Domain (information that is common property and contains no original authorship)).

Figure 12.4: Katz places the production of emotion into a larger complex social and societal setting when he discusses anger among car drivers in Los Angeles

12.2 Emotion in Technology?

A part of the new wave of research on emotion also affected research and innovation of new technology. In artificial intelligence, emotion had to be considered as an important regulatory process, determining behaviour in autonomous systems of various kinds, e.g. robots trying to survive in a dynamically changing world (see e.g. Cañamero, 2005).

In HCI, we understood the importance of considering users’ emotions explicitly in our design and evaluation processes. Broadly, the HCI research came to go in three different directions with three very different theoretical perspectives on emotion and design.

1. The first, widely known and very influential perspective is that of Rosalind Picard and her group at MIT, later picked up by many other groups, in Europe most notably by the HUMAINE network. The cognitivistically inspired design approach she named Affective Computing in her groundbreaking book from 1997.

2. The second design approach might be seen as a counter-reaction to Affective Computing. Instead of starting from a more traditional perspective on cognition and biology, the Affective Interaction approach starts from a constructive, culturally-determined perspective on emotion. Its most well-known proponents are Phoebe Sengers, Paul Dourish, Bill Gaver and to some extent myself (Boehner et al., 2007, Boehner et al. 2005, Gaver 2009, Sundström et al. 2007, Höök, 2006, Höök 2008, Höök 2009).

3. Finally, there are those who think that singling out emotion from the overall interaction leads us astray. Instead, they see emotion as part of a larger whole of experiences we may design for – we can name the movement Technology as Experience. In a sense, this is what traditional designers and artists have always worked with (see e.g. Dewey 1934) – creating for interesting experiences where some particular emotion is a cementing and congruous force that unites the different parts of the overall system of art piece and viewer/artist. Proponents of this direction are, for example, John McCarthy, Peter Wright, Don Norman and Bill Gaver (McCarthy and Wright, 2004, Norman, 2004, Gaver, 2009).

Let us develop these three directions in some more detail. They have obvious overlaps, and in particular, the Affective Interaction and Technology as Experience movements have many concepts and design aims in common. Still, if we simplify them and describe them as separate movements, it can help us to see the differences in their theoretical underpinnings.

12.2.1 Affective Computing

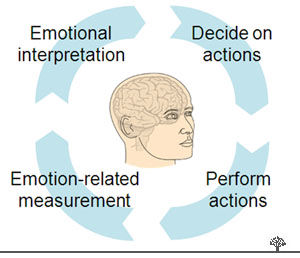

The artificial intelligence (AI) field picked up the idea that human rational thinking depends on emotional processing. Rosalind Picard’s “Affective Computing” had a major effect on both the AI and HCI fields (Picard, 1997). Her idea, in short, was that it should be possible to create machines that relate to, arise from, or deliberately influence emotion or other affective phenomena. The roots of affective computing really came from neurology, medicine, and psychology. It implements a biologistic perspective on emotion processes in the brain, body, and interaction with others and with machines.

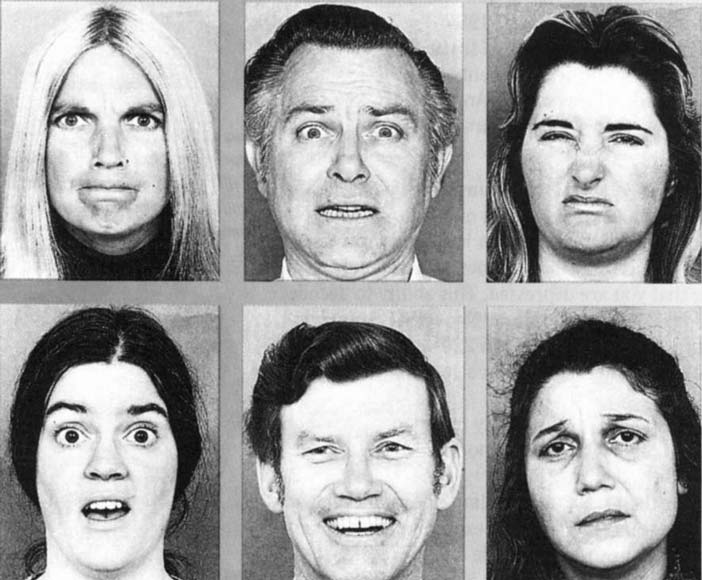

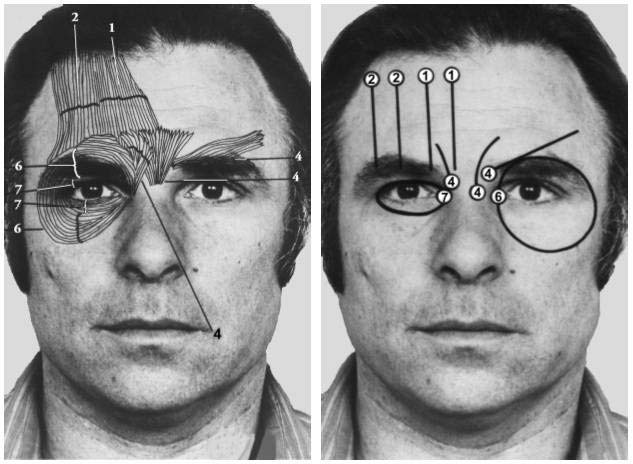

The most discussed and widespread approach in the design of affective computing applications is to construct an individual cognitive model of affect from what is often referred to as “first principles”, that is, the system generates its affective states and corresponding expressions from a set of general principles rather than having a set of hardwired signal-emotion pairs. This model is combined with a model that attempts to recognize the user’s emotional states through measuring the signs and signals we emit in face, body, voice, skin, or what we say related to the emotional processes going on. In Figure 5 we see for example how facial expressions, portraying different emotions, can be analysed and classified in terms of muscular movements.

Author/Copyright holder: Paul Ekman 1975. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.5: Facial expressions from Ekman portraying anger, fear, disgust, surprose, happiness and sadness

Author/Copyright holder: Greg Maguire. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 5B: Facial muscles moving eyebrow and muscles around the eye when expressing different emotions

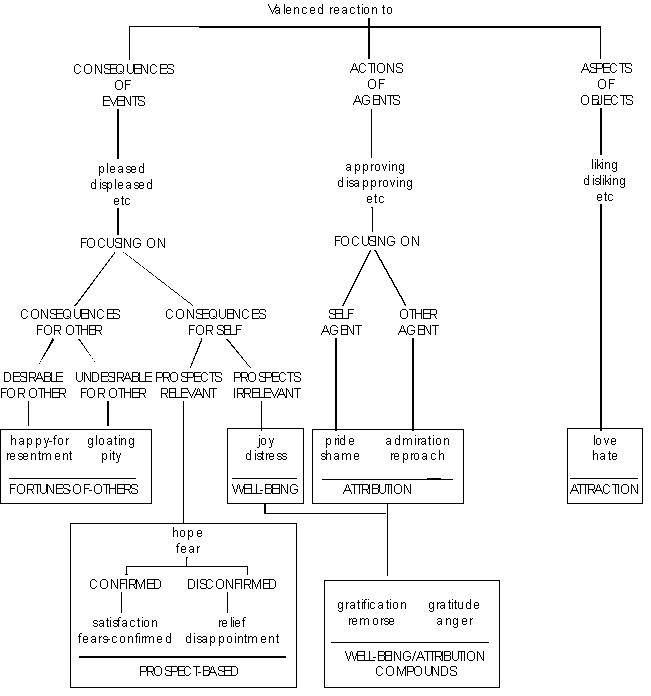

Emotions, or affects, in users are seen as identifiable states or at least identifiable processes. Based on the identified emotional state of the user, the aim is to achieve an interaction as life-like or human-like as possible, seamlessly adapting to the user’s emotional state and influencing it through the use of various expressions. This can be done through applying rules such as those brought forth by Ortony et al. 1988, see Figure 6.

Author/Copyright holder: Ortony, Clore and Collins. Copyright terms and licence: From The cognitive structure of emotions (1988). Cambridge University Press. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.6: A rule from the OCC-model (Ortony et al., 1988)

This model has its limitations, both in its requirement for simplification of human emotion in order to model it, and in its difficult approach into how to infer the end-users emotional states through interpreting human behaviour through the signs and signals we emit. This said, it still provides for a very interesting way of exploring intelligence, both in machines and in people.

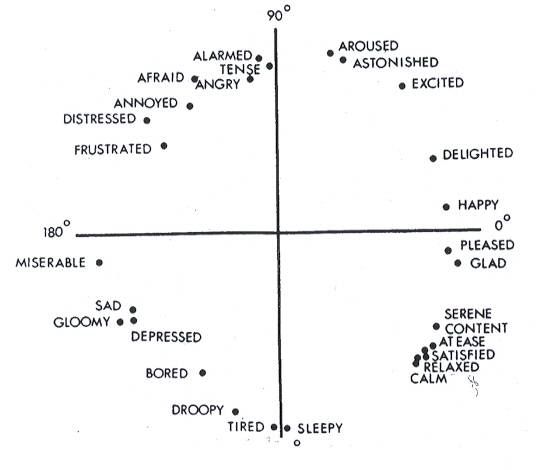

Examples of affective computing systems include, for example, Rosalind Picard and colleagues’ work on affective learning. It is well known that students’ results can be improved with the right encouragement and support (Kort et al., 2001). They therefore propose an emotion model built on James A. Russell’s circumplex model of affect relating phases of learning to emotions, see Figure 7. The idea is to build a learning companion that keeps track of what emotional state the student is in and from that decides what help she needs.

Author/Copyright holder:James A. Russell and American Psychological Association. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.7: Russell's circumplex model of affect

But the most interesting applications from Rosalind Picard’s group deal with important issues such as how to train autistic children to recognise emotional states in others and in themselves and act accordingly. In a recent spin-off company, named Affectiva, they put their understanding into commercial use – both for the autistic children, but also for recognising interest in commercials or dealing with stress in call centres. A sensor bracelet recognising Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) is used in their various applications, see Figure 8.

Author/Copyright holder: Affectiva, Inc. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.8: The bracelet, named Q Sensor, measures skin conductance which in turn is related to emotional arousal - both positive and negative

Other groups, like the HUMAINE network in Europe, starts from this way of seeing affective interaction.

Author/Copyright holder: Phoebe Sengers, Kirsten Boehner, Simeon Warner, and Tom Jenkin. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.9: Samples of Affector Output

12.2.2 Affective Interaction: The Interactional Approach

An affective interactional view is different from the affective computing approach in that it sees emotions as constructed in interaction, whereas a computer application supports people in understanding and experiencing their own emotions (Boehner et al., 2005, Boehner et al 2007, Höök et al., 2008, Höök 2008). An interactional perspective on design will not aim to detect a singular account of the “right” or “true” emotion of the user and tell them about it as in a prototypical affective computing application, but rather make emotional experiences available for reflection. Such a system creates a representation that incorporates people’s everyday experiences that they can reflect on. Users’ own, richer interpretation guarantees that it will be a more “true” account of what they are experiencing.

According to Kirsten Boehner and colleagues (2007)), the interactional approach to design:

recognizes affect as a social and cultural product

relies on and supports interpretive flexibility

avoids trying to formalize the unformalizable

supports an expanded range of communication acts

focuses on people using systems to experience and understand emotions

focuses on designing systems that stimulate reflection on and awareness of affect

Later, I and my colleagues added two minor modifications to this list (Höök et al., 2008):

Modification of #1: The interactional approach recognizes affect as an embodied social, bodily and cultural product

Modification of #3: The interactional approach is non-reductionist

The first change is related to the bodily aspects of emotional experiences. But explicitly pointing to them, we want to add some of the physical and bodily experiences that an interaction with an affective interactive system might entail. We also took a slightly different stance towards design principle number three, “the interactional approach avoids trying to formalize the unformalizable”, in Boehner and colleagues’ list of principles. To avoid reductionist ways of accounting for subjective or aesthetic experiences, Boehner and colleagues’ aim to protect these concepts by claiming that human experience is unique, interpretative, and ineffable. Such a position risks mystifying human experience, closing it off as ineffable and thereby enclosing it to be beyond study and discussion. While I wholeheartedly support the notion of unity of experience and support the idea of letting the magic of people’s lives remain unscathed, I do believe that it is possible to find a middle ground where we can actually speak about qualities of experiences and knowledge on how to design for them without reducing them to something less than the original. This does not in any way mean that the experiential strands, or qualities, are universal and the same for everyone. Instead they are subjective and experienced in their own way by each user (McCarthy and Wright, 2004).

A range of systems has been built to illustrate this approach, such as Affector (Sengers et al., 2005), the VIO (Kaye, 2006), eMoto (Sundström et al., 2009), Affective Diary (Ståhl et al., 2009) and Affective Health (Ferreira et al., 2010) – just to mention a few.

Affector is a distorted video window connecting neighbouring offices of two friends (and colleagues), see Figure 9. A camera located under the video screen captures video as well as 'filter' information such as light levels, colour, and movement. This filter information distorts the captured images of the friends that are then projected in the window of the neighbouring office. The friends determine amongst themselves what information is used as a filter and various kinds of distortion in order to convey a sense of each other's mood.

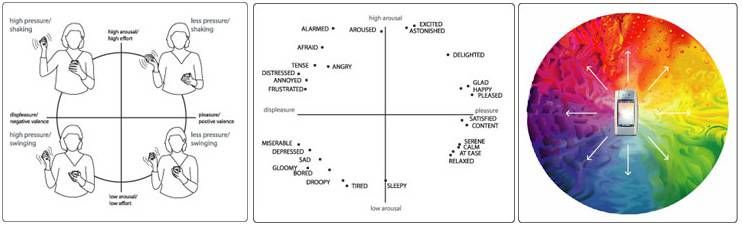

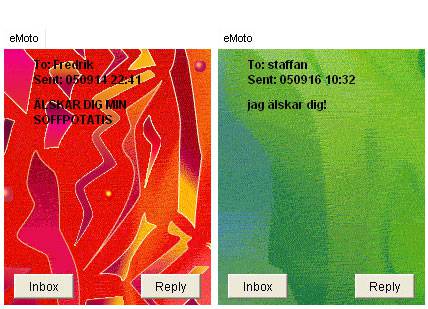

eMoto is an extended SMS-service for the mobile phone that lets users send text messages between mobile phones, but in addition to text, the messages also have colourful and animated shapes in the background (see examples in Figure 11). To choose an expression, you perform a set of gestures using the stylus pen (that comes with some mobile phones), which we had extended with sensors that could pick up on pressure and shaking movements. Users are not limited to any specific set of gestures but are free to adapt their gesturing style according to their personal preferences. The pressure and shaking movements can act as a basis for most emotional gestures people do, a basis that allows users to build their own gestures on top of these general characteristics, see Figure 11.

Author/Copyright holder: Petra Sundström, Anna Ståhl, and Kristina Höök (images to the left and right) and James A. Russell and American Psychological Association (the image in the middle). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.10: Different physical movements (left) that remind of the underlying affective experiences of the circumplex model of affect from Russell (middle), which is then mapped to a colourful, animated expression (right), also mapped to the circumplex model of affect

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation). See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.11: eMoto-messages sent to boyfriends in the final study of eMoto. On the left, a high energy expression of love from study participant Agnes to her boyfriend. On the right, Mona uses her favourite green colours to express her love for her boyfriend

Affective Diary works as follows: as a person starts her day, she puts on a body sensor armband. During the day, the system collects time stamped sensor data picking up movement and arousal. At the same time, the system logs various activities on the mobile phone: text messages sent and received, photographs taken, and Bluetooth presence of other devices nearby. Once the person is back at home, she can transfer the logged data into her Affective Diary. The collected sensor data are presented as somewhat abstract, ambiguously shaped, and coloured characters placed along a timeline, see Figure 12. To help users reflect on their activities and physical reactions, the user can scribble diary-notes onto the diary or manipulate the photographs and other data, see example from one user in Figure 12.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation). See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.12: The Affective Diary system. Bio-sensor data are represented by the blobby figures at the bottom of the screen. Mobile data are inserted in the top half of the screen along the same time-line as the blobby characters

![A user says about this screendump: “[pointing at the orange character] And then I become like this, here I am kind of, I am kind of both happy and sad in some way and something like that. I](https://public-media.interaction-design.org/images/encyclopedia/affective_computing/affective_diary_13_interactional_approach_to_affective_design.jpg)

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown (pending investigation). Copyright terms and licence: Unknown (pending investigation). See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 12.13: A user says about this screendump: “[pointing at the orange character] And then I become like this, here I am kind of, I am kind of both happy and sad in some way and something like that. I like him and then it is so sad that we see each other so little. And then I cannot really show it.

As can be seen from all these three examples, an interactional approach to design tries to avoid reducing human experience to a set of measurements or inferences made by the system to interpret users’ emotional states. While the interaction of the system should not be awkward, the actual experiences sought might not only be positive ones. eMoto may allow you to express negative feelings about others. Affector may communicate your negative mood. Affective Diary might make negative patterns in your own behaviour painfully visible to you. An interactional approach is interested in the full (infinite) range of human experience possible in the world.

12.2.3 Technology as Experience

While we have so far, in a sense, separated out emotion processes from other aspects of being in the world, there are those who posit that we need to take a holistic approach to understanding emotion. Emotion processes are part of our social ways of being in the world, they dye our dreams, hopes, and experiences of the world. If we aim to design for emotions, we need to place them in the larger picture of experiences, especially if we are going to address aspects of aesthetic experiences in our design processes (Gaver, 2009, McCarthy and Wright, 2004, Hassenzahl, 2008).

John Dewey, for example, distinguishes aesthetic experiences from other aspects of our life through placing it in-between two extremes on a scale (Dewey, 1934). On the one end of that scale, we just drift and experience an unorganized flow of events in everyday life, and on the other end of the scale we experience events that do have a clear beginning and end but that only mechanically connect the events with one-another. Aesthetic experiences exist between those extremes. They have a beginning and an end; they can be uniquely named afterwards, e.g. “when I took those horseback riding lessons with Christian in Cambridge” (Höök, 2010), but in addition, the experience has a unity – there is a single quality that pervades the entire experience (Dewey 1934, p. 36-57):

An experience has a unity that gives it its name, that meal, that storm, that rupture of a friendship. The existence of this unity is constituted by a single quality that pervades the entire experience in spite of the variation of its constituent parts

In Dewey’s perspective, emotion is (Dewey, 1934 p. 44):

the moving and cementing force. It selects what is congruous and dyes what is selected with its color, thereby giving qualitative unity to materials externally disparate and dissimilar. It thus provides unity in and through the varied parts of an experience

However emotions are not static but change in time with the experience itself, just as a dramatic experience does (Dewey 1934, p. 43).

Joy, sorrow, hope, fear, anger, curiosity, are treated as if each in itself were a sort of entity that enters full-made upon the scene, an entity that may last a long time or a short time, but whose duration, whose growth and career, is irrelevant to its nature. In fact emotions are qualities, when they are significant, of a complex experience that moves and changes.

While an emotion process is not enough to create an aesthetic experience, emotions will be part of the experience and inseparable from the intellectual and bodily experiences. In such a holistic perspective, it will not make sense to talk about emotion processes as something separate from our embodied experience of being in the world.

Bill Gaver makes the same argument when discussing design for emotion (Gaver 2009). Rather than isolating emotion as if it is something that “can be canned as a tomato in a Campbell tomato soup” (as John Thackara phrased it when he criticised the work by Don Norman on the subject), we need to consider a broader view on interaction design, allowing for individual appropriation. Bill Gaver phrases it clearly when he writes:

Clearly, emotion is a crucial facet of experience. But saying that it is a ‘facet of experience’ suggests both that it is only one part of a more complex whole (the experience) and that it pertains to something beyond itself (an experience of something). It is that something—a chair, the home, the challenges of growing older—which is an appropriate object for design, and emotion is only one of many concerns that must be considered in addressing it. From this point of view, designing for emotion is like designing for blue: it makes a modifier a noun. Imagine being told to design something blue. Blue what? Whale? Sky? Suede shoes? The request seems nonsensical

If we look back at the Affector, eMoto, and Affective Diary systems, we see clearly that they are designed for something else than the isolation of emotion. Affector and eMoto are designed for and used for communication between people where emotion is one aspect of their overall communication. And, in fact, Affector turned out to not really be about emotion communication, but instead became a channel for a sympathetic mutual awareness of your friend in the other office.

12.3 Concluding remarks - some directions for the future

It seems obvious that we cannot ignore the importance of emotion processes when designing for experiences. On the other hand, designing as if emotion is a state that can be identified in users taken out of context, will not lead to interesting applications in this area. Instead, the knowledge on emotion processing needs to be incorporated in our overall design processes.

The work in all the three directions of emotion design outlined above contributes in different ways to our understanding of how to increase our knowledge on how to make emotion processes an important part of our design processes. The Affective Computing field has given us a range of tools for both affective input, such as facial recognition tools, voice recognition, body posture recognition, bio-sensor models, and tools for affective output e.g. emotion expression for characters in the interface or regulating robot behaviours. The Affective Interaction strand has contributed to an understanding of the socio-cultural aspects of emotion, situating them in their context, making sure that they are not only described as bodily processes beyond our control. The Technology as Experience-field has shifted our focus from emotion as an isolated phenomenon towards seeing emotion processes as one of the (important) aspects to consider when designing tools for people.

There are still many unresolved issues in all these three directions. In my own view, we have not yet done enough to understand and address the everyday, physical, and bodily experiences of emotion processes (e.g. Sundström et al., 2007, Ståhl et al., 2009, Höök et al., 2008, Ferreira et al., 2008, Ferreira et al., 2010, Sundström et al., 2009, Ferreira and Höök, 2011). Already Charles Darwin made a strong coupling between emotion and bodily movement (Darwin, 1872). Since then, researchers in areas as diverse as neurology (leDoux 1996, Davidson et al., 2003), philosophy and dance (Sheets-Johnstone, 1999, Laban and Lawrence, 1974), and theatre (Boal, 1992), describe the close coupling between readiness to action, muscular activity, and the co-occurrence of emotion.

I view our actual corporeal bodies as key in being in the world, in creating for experiences, learning and knowing, as Sheets-Johnstone has discussed (1999). Our bodies are not instruments or objects through which we communicate information. Communication is embodied - it involves our whole selves. In design, we have had a very limited view on what the body can do for us. Partly this was because the technology was not yet there to involve more senses, movements and richer modalities. Now, given novel sensing and actuator materials, there are many different kinds of bodily experiences we can envision designing for - mindfulness, affective loops, excitement, slow inwards listening, flow, reflection, or immersion (see e.g. Moen, 2006, Isbister and Höök, 2009, Hummels et al., 2007). In the recently emerging field of design for somaesthetics (Schiphorst, 2007), interesting aspects of bodily learning processes, leading to stronger body awareness are picked up and explicitly used in design. This can be contrasted with the main bulk of e.g. commercial sports applications, such as pedometers or pulse meters, where the body is often seen as an instrument or object for the mind, passively receiving sign and signals, but not actively being part of producing them. Recently, Purpura and colleagues (2011) made use of a critical design method to pinpoint some of the problems that follows from this view. Through describing a fake system, Fit4Life, measuring every aspect of what you eat, they arrive at a system that may whisper into your ear "I'm sorry, Dave, you shouldn't eat that. Dave, you know I don't like it when you eat donuts" just as you are about to grab a donut. This fake system shows how we may easily cross the thin line from persuasion to coercion, creating for technological control of our behavior and bodies. In my view, by designing applications with an explicit focus on aesthetics, somaesthetics, and empathy with ourselves and others, we can move beyond impoverished interaction modalities and treating our bodies as mere machines that can be trimmed and controlled, towards richer, more meaningful interactions based on our human ways of physically inhabiting our world.

We are just at the beginnings of unravelling many novel design possibilities as we approach emotions and experiences more explicitly in our design processes. This is a rich field of study that I hope will attract many young designers, design researchers and HCI-experts.

12.4 References

Boal, Augusto (1992): Games for Actors and Non-Actors. Routledge

Boehner, Kirsten, dePaula, Rogerio, Dourish, Paul and Sengers, Phoebe (2007): How emotion is made and measured. In International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 65 (4) pp. 275-291

Boehner, Kirsten, dePaula, Rogerio, Dourish, Paul and Sengers, Phoebe (2005): Affect: from information to interaction. In: Bertelsen, Olav W., Bouvin, Niels Olof, Krogh, Peter Gall and Kyng, Morten (eds.) Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing 2005 August 20-24, 2005, Aarhus, Denmark. pp. 59-68

Cañamero, Lola (2005): Emotion understanding from the perspective of autonomous robots research. In Neural Networks, 18 (4) pp. 445-455

Damasio, Antonio R. (1995): Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Harper Perennial

Darwin, Charles (0000): The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London, UK, John Murray

Davidson, Richard J., Scherer, Klaus R. and Goldsmith, H. Hill (2002b): Handbook of Affective Sciences. Oxford University Press, USA

Davidson, Richard J., Pizzagalli, Diego, Nitschke, Jack B. and Kalin, Ned H. (2002a): Parsing the subcomponents of emotion and disorders of emotion: perspectives from affective neuroscience. In: Davidson, Richard J., Scherer, Klaus R. and Goldsmith, H. Hill (eds.). "Handbook of Affective Sciences". Oxford University Press, USA

dePaula, Rogerio and Dourish, Paul (2005): Cognitive and Cultural Views of Emotions. In: Proceedings of the Human Computer Interaction Consortium Winter Meeting 2005, Douglas, CO, USA.

Dewey, John (1934): Art as Experience. Perigee Trade

Dunbar, Robin (1997): Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language. Harvard University Press

Dunbar, Robin (1998): Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language. Harvard University Press

Ellsworth, Phoebe C. and Scherer, Klaus R. (2003): Appraisal processes in emotion. In: Davidson, Richard J., Sherer, Klaus R. and Goldsmith, H. Hill (eds.). "Handbook of Affective Sciences". Oxford University Press, USA

Ferreira, Pedro and Höök, Kristina (2011): Bodily Orientations around Mobiles: Lessons learnt in Vanuatu. In:Proceedings of the ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 7-12 May, 2011, Vancouver, Canada.

Ferreira, Pedro, Sanches, Pedro, Höök, Kristina and Jaensson, Tove (2008): License to chill!: how to empower users to cope with stress. In: Proceedings of the Fifth Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 2008. pp. 123-132

Gaver, William (2009): Designing for emotion (among other things). In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 364 (1535) pp. 3597-3604

Grosz, Elizabeth (1994): Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Theories of Representation and Difference). Indiana University Press

Hummels, Caroline, Overbeeke, Kees and Klooster, Sietske (2007): Move to get moved: a search for methods, tools and knowledge to design for expressive and rich movement-based interaction. In Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 11 (8) pp. 677-690

Hutchins, Edwin (1995): Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press

Höök, Kristina (2009): Affective loop experiences: designing for interactional embodiment. In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 364 p. 3585–3595

Höök, Kristina (2008): Affective Loop Experiences - What Are They?. In: Oinas-Kukkonen, Harri, Hasle, Per F. V.,Harjumaa, Marja, Segerståhl, Katarina and Øhrstrøm, Peter (eds.) PERSUASIVE 2008 - Persuasive Technology, Third International Conference June 4-6, 2008, Oulu, Finland. pp. 1-12

Höök, Kristina (2006): Designing familiar open surfaces. In: Proceedings of the Fourth Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 2006. pp. 242-251

Höök, Kristina (2010): Transferring qualities from horseback riding to design. In: Proceedings of the Sixth Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 2010. pp. 226-235

Höök, Kristina, Ståhl, Anna, Sundström, Petra and Laaksolaahti, Jarmo (2008): Interactional empowerment. In:Proceedings of ACM CHI 2008 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems April 5-10, 2008. pp. 647-656

Isbister, Katherine and Höök, Kristina (2009): On being supple: in search of rigor without rigidity in meeting new design and evaluation challenges for HCI practitioners. In: Proceedings of ACM CHI 2009 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2009. pp. 2233-2242

Katz, Jack (2001): How Emotions Work. University of Chicago Press

Katz, Jack (1999): How Emotions Work. University of Chicago Press

Kaye, Joseph Jofish (2006): I just clicked to say I love you: rich evaluations of minimal communication. In: Olson, Gary M. and Jeffries, Robin (eds.) Extended Abstracts Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems April 22-27, 2006, Montréal, Québec, Canada. pp. 363-368

Kort, Barry, Reilly, Rob and Picard, Rosalind W. (2001): An Affective Model of Interplay between Emotions and Learning: Reengineering Educational Pedagogy - Building a Learning Companion. In: ICALT 2001 2001. pp. 43-48

Laban, Rudolf von and Lawrence, F. C. (1974): Effort: economy in body movement. Plays, inc

Ledoux, Joseph (1996): The Emotional Brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon and Schuster

Ledoux, Joseph (1998): The Emotional Brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon and Schuster

Longo, Giuseppe O. (2003): Body and Technology: Continuity or Discontinuity?. In: Fortunati, Leopoldina, Katz, James E. and Riccini, Raimonda (eds.). "Mediating the Human Body: Technology, Communication, and Fashion". Routledge

Lutz, Catherine (1986): Emotion, Thought, and Estrangement: Emotion as a Cultural Category. In Cultural Anthropology, 1 (3) pp. 287-309

Lutz, Catherine A. (1988): Unnatural Emotions: Everyday Sentiments on a Micronesian Atoll and Their Challenge to Western Theory. University of Chicago Press

McCarthy, John and Wright, Peter (2004): Technology as Experience. The MIT Press

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1958): Phenomenology of Perception. London, England, Routledge

Moen, Jin (2006). KinAesthetic Movement Interaction : Designing for the Pleasure of Motion (Doctoral Thesis). KTH

Norman, Donald A. (2004): Emotional Design: Why We Love (Or Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Books

Ortony, Andrew, Clore, Gerald L. and Collins, Allan (1988): The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge University Press

Ortony, Andrew, Clore, Gerald L. and Collins, Allan (1990): The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge University Press

Parkinson, B. (1996): Emotions are social. In British Journal of Psychology, 87 p. 663–683

Picard, Rosalind W. (1997): Affective computing. Ma, USA, The MIT Press

Purpura, Stephen, Schwanda, Victoria, Williams, Kaiton, Stubler, William and Sengers, Phoebe (2011): Fit4life: the design of a persuasive technology promoting healthy behavior and ideal weight. In: Proceedings of ACM CHI 2011 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2011. pp. 423-432

Russell, James A. (1980): Circumplex Model of Affect. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39 (6) pp. 1161-1178

Sanches, Pedro, Höök, Kristina, Vaara, Elsa, Weymann, Claus, Bylund, Markus, Ferreira, Pedro, Peira, Nathalie andSjölinder, Marie (2010): Mind the body!: designing a mobile stress management application encouraging personal reflection. In: Proceedings of DIS10 Designing Interactive Systems 2010. pp. 47-56

Schiphorst, Thecla (2007): Really, really small: the palpability of the invisible. In: Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Creativity and Cognition 2007, Washington DC, USA. pp. 7-16

Sengers, Phoebe, Boehner, Kirsten, Warner, Simeon and Jenkins, Tom (2005): Evaluating Affector: Co-Interpreting What 'Works'. In: CHI 2005 Workshop on Innovative Approaches to Evaluating Affective Systems 2005.

Sheets-Johnstone, Maxine (2009): The Corporeal Turn: An Interdisciplinary Reader. Imprint Academic

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (1999): Emotion and Movement: A beginning Empirical-Phenomenological Analysis of Their Relationship. In Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6 (11) pp. 259-277

Shusterman, Richard (2008): Body Consciousness: A Philosophy of Mindfulness and Somaesthetics. Cambridge University Press

Ståhl, Anna, Höök, Kristina, Svensson, Martin, Taylor, Alex S. and Combetto, Marco (2009): Experiencing the Affective Diary. In Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 13 (5) pp. 365-378

Sundström, Petra, Ståhl, Anna and Höök, Kristina (2007): In situ informants exploring an emotional mobile messaging system in their everyday practice. In International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 65 (4) pp. 388-403

Sundström, Petra, Jaensson, Tove, Höök, Kristina and Pommeranz, Alina (2009): Probing the potential of non-verbal group communication. In: GROUP09 - International Conference on Supporting Group Work 2009. pp. 351-360