Writing your portfolio UX case studies is easier when you follow a simple structure: a beginning, a middle and an end part. As with practically everything else in the field of writing, knowing what to do where and what to save for later is vital. That’s why, here, we will get you off to a good start, by giving you a few tips on how to write the perfect beginning to your case study.

Sometimes, making a start is the most difficult part of a project. Writing your own UX case studies can be an intimidating task. After all, they are the most important part of your UX portfolio, and only if you get them right will you stand a chance of being invited for an interview, where you will really have an opportunity to let your personality and professional skills shine. So, where do you begin?

The role of a UX case study’s beginning section

A UX case study tells a story. More precisely, it follows one of the most well-known story structures in literature: a story based on an idea. Idea stories start by raising a question – for instance, what if an alien civilization made contact with us? What would the world look like if Hitler had won in WW2? How would people behave if the government could monitor them at all times?

Great questions make for amazing novels and films. They also make for great UX case studies. When you’re writing your case study, all you are doing is really expressing the question, the premise that challenged you to think and employ your skills, and the motivation behind all the discoveries you made (and which you are going to tell the recruiters about in the case study).

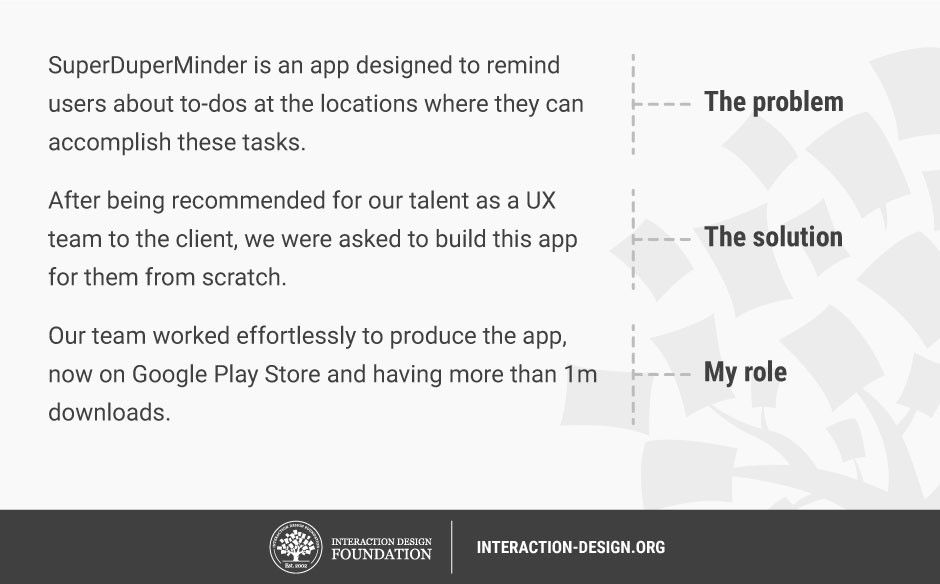

Therefore, your beginning section must set the stage, or frame, for the rest of the story. Here, you will write about the project, its goals, why they were important, and what your role was in seeing the project through to the end. A common portfolio mistake is to jump straight into the design details, without giving the recruiter a clear overview of the project’s scope. You might therefore consider having three separate subheadings in this section:

The Problem: A problem statement introduces why you undertook this work and whom you did this for. What were the challenges and barriers that you tried to overcome? What would be the payoff if you managed to do it?

The Solution: Here, you might outline your approach to tackling the problem and why it was important to follow that strategy.

My Role: Finally, you should explain what role you played in this project. This is important. If you are applying for a user researcher role, then your case study should be about something you did that included user research. You might have also done other things, but tailor the case study to focus more on the work you did on the aspect that fits the role you are applying for.

Writing the beginning of the case study can take whatever form you like. You can include the above information under separate headings, or you can write it all in a paragraph. No matter the case, the content shouldn’t be longer than 4-5 sentences. The story of how the project came to be could be really interesting, but it’s not why recruiters will be hiring you. So, keep it short, and super-focused. Remember, the goal is to give some context about the work you did on that project and nothing more.

Turning a bad example into a great one

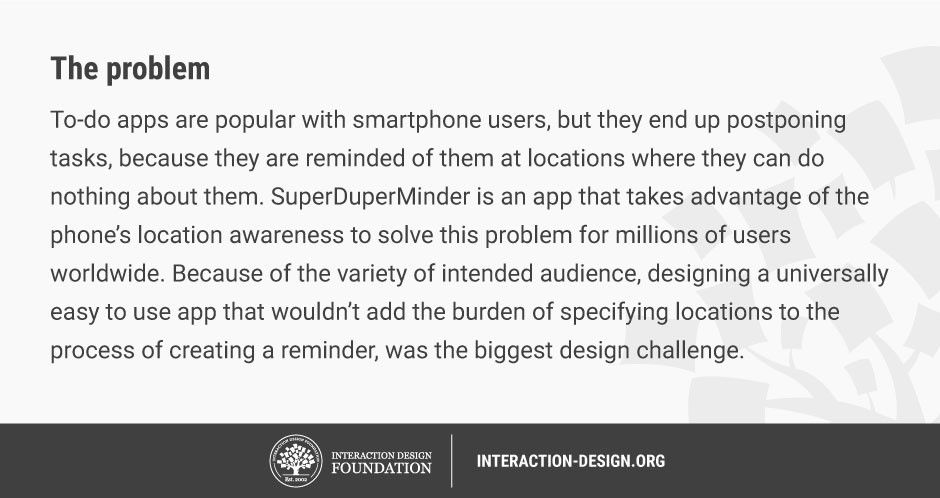

Let’s take an example of a bad introduction to a UX case study and break it down, so we can highlight some important mistakes.

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Starting off with an introduction and not doing too well, since there is no sight of the challenges or barriers that we needed to overcome in the project, or the importance of the work.

The description starts off with the scope of the project – i.e., what the end goal (to design a new app for location-based reminders) was. But it tells us nothing about the challenges or barriers that the designers needed to overcome. We have no understanding of whether this was a difficult or easy problem. And we certainly don’t know the payoff – whom is this for? Why is it important that it is built? What needs does it meet? Let’s improve on that sentence.

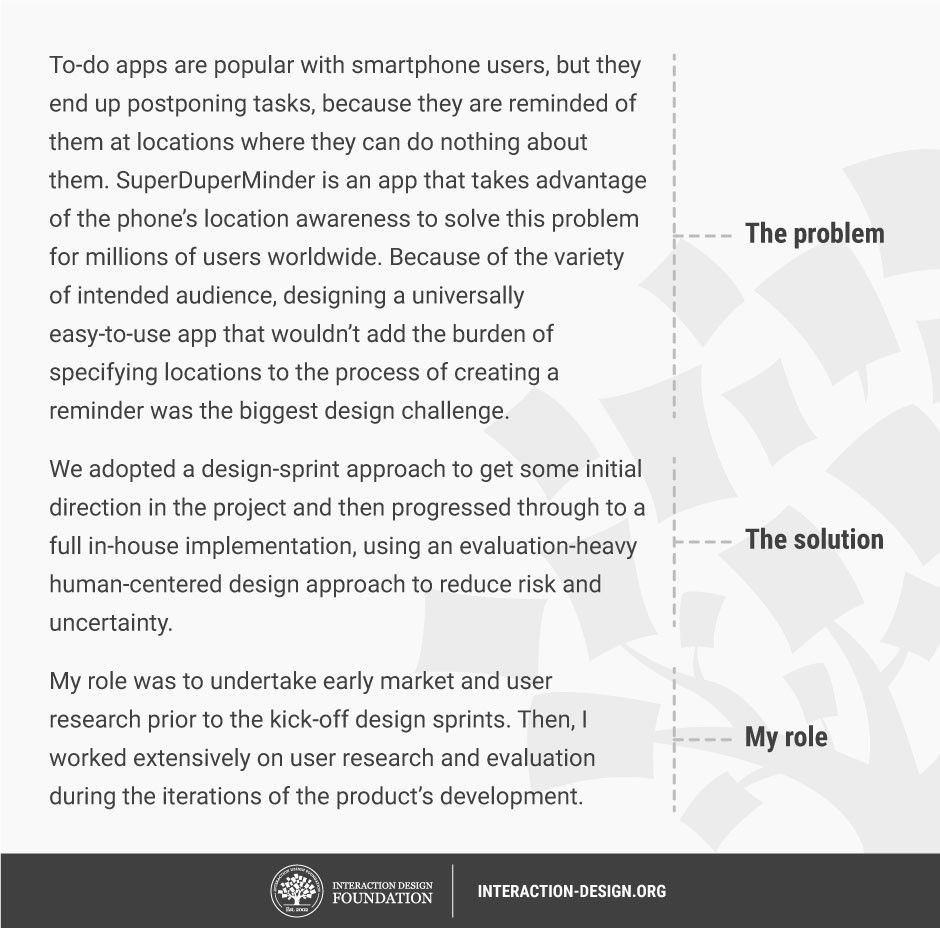

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

A better phrasing for the starting problem statement – It’s quite long, though!

Note in the example above that we clearly introduced the problem, the payoff and the challenge. Now, let’s tackle the solution part. In our bad example, the solution was simply stated as “being asked to build the app from scratch” – but that says nothing about how we approached the challenges of the project. Also, the statement about a recommendation from another client says nothing to your recruiter about how you approached the project. Let’s rephrase it.

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

A better phrasing for the solution statement, now including some insights on our methodology.

In this rephrasing, we have divulged a wealth of information: our knowledge of two popular industry methodologies and the value we place on evaluation and role in mitigating risks.

Now, let’s look at the third part: It talks about what the team did, but the recruiter isn’t hiring the team; the recruiter is hiring you. The statement about the 1m downloads probably means you did something right after all, but it doesn’t say much on its own – after all, most users uninstall apps a few minutes after they have downloaded them. You are better off leaving impact statements for the end of your case study, anyway. Let’s rephrase this.

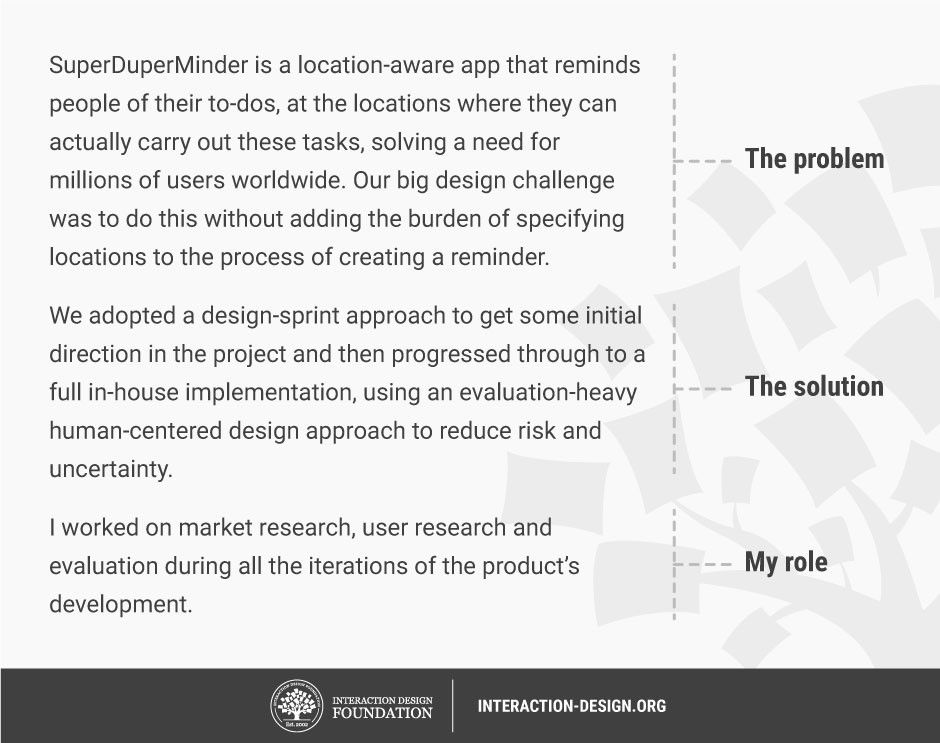

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

A better phrasing for the role statement, focusing on the work we did individually as part of a team.

Let’s now put it all together:

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

The first revision of our introduction – It is much more relevant than the initial introduction, but it’s now rather long.

That’s 6 sentences in all – a bit over our desired 4-5. Can we make it shorter? Let’s try.

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Second revision of the introduction, now shortened to the desired 4-5-sentence length.

There we go! That’s 4 sentences that give a full account of the project’s background. It’s always best to leave yourself free to write as much as you think is required at first. Then, you can begin stripping back the text to the required 4-5 sentences. To do this, follow Brutal Pixie’s golden rule to content simplicity:

“Subtract the obvious, add the meaningful.”

Brutal Pixie, content strategist

Copyright holder: BK, Flickr. Copyright terms and license: CC BY 2.0

Take the first step into writing with an eager attitude. Communication skills are crucial to your professional life as a UX designer. Don’t see writing your case studies as a chore, but as a chance to improve and develop yourself professionally.

Think about what you really want to say here — what are the key takeaways that whoever is reading this must discover? Rephrase your writing to ensure that all the important details are there, but in a short and concise form. It takes some practice, but you can do it. Most importantly, however, don’t forget to have key takeaways for the Problem, Solution and Role elements of your case study beginning. Katherine Firth, a teacher of research and writing skills at La Trobe University and the University of Melbourne, provides a few excellent tips to make your writing more concise (2015). If you’re having trouble molding what you want to write into a sharper, more streamlined “spearhead” that gets to the point every time and makes a deep impression, we highly recommend going through her article (see the references section).

Use active instead of passive voice.

Get rid of adverbs and reduce your adjectives.

Use the shortest form of the word.

Use the shortest form of a phrase.

Keep your sentences to 25-30 words.

The Take Away

Case study beginning sections take some time to master to write. They need to be quite short, but also contain all the crucial details that will explain the project’s context to your recruiters, and show them why you thought this might be a good case study to include in your portfolio. Keeping things short and tight takes a bit of practice, but even if you can’t keep to the 4-5 sentence guideline, at the very least pay special attention to ensuring that all of the key elements of the case study beginning are present. Remember, what the recruiters will read is a “solution”, in a sense, to the “problem” of how to present the most outstanding case study. In the process, you want to show how adept you are at tackling problems overall and, in particular, finding results that win for them and the users.

References & Where to Learn More

Hero Image: Copyright holder: MemoryCatcher, pixabay.com. Copyright terms and license: CC0

Course: “User Experience: The Beginner’s Guide”.

Firth, K. (2015). 10 tips for more concise writing.