Language is much less neutral than what you often realize. The truth is that your choice for words does affect and/or is a reflection of how you see the world. This is why, as a user experience practitioner, you need to place special awareness on the connotations of the terms you pick.We do have techniques – such as card-sorting – that help us with labels selection. But the question here is much deeper: how do you call the people you are designing for?

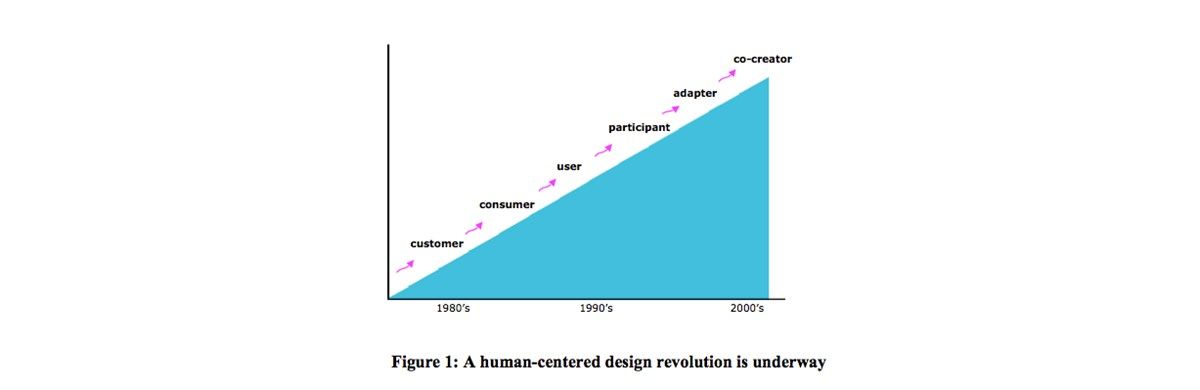

Look at the image above from Liz Sanders; founder of the company MakeTools. It provides a clear overview of the most common words that are used to describe people who buy and use the products and services that we design.

The language of these labels shapes the way that we think about these people. As a designer, you should be aware of the context that labels bring: each one of these concepts implies a different mind-set and also requires for a specific set of tools.

Let’s see how this applies to the user-related labels:

“Customer or Consumer”: This is, perhaps, the most commonly used and understood term to describe those who will interact with our designs.

It’s worth noting that there is a “negative connotation” to this label in some circumstances – it can convey the idea that our users are passive. Customers, traditionally at least, exist outside of our design processes; they don’t have voices or opinions. Experts show customers the way forward and they define what customers need and will buy.

Along these lines, we find quotes such as: “designers typically do not solve problems; they go one step beyond and create a new reality for people to explore. The designer as a problem-solver is a popular misconception.” This is what KeesOverbeeke and Caroline Hummels claim in their chapter on Industrial Design.On the other hand, you as a UX practitioner can state that nowadays the majority of design work is more about bridging and covering gaps than creating new realities.

The fashion world is a good example of these two approaches to design. On one side, we have the “haute couture” and famous designers setting the trends. On the other hand, we have companies such as Zara - the major fashion retailer - that removes any product that doesn’t sale. Conversely, when a product works well, another similar product will be designed to complement it. It only takes Zara about 3 weeks to design, produce and ship new products. They may not think of this process as user-centred design but it sure has a lot of similarities to it, doesn’t it?

From users to co-creators

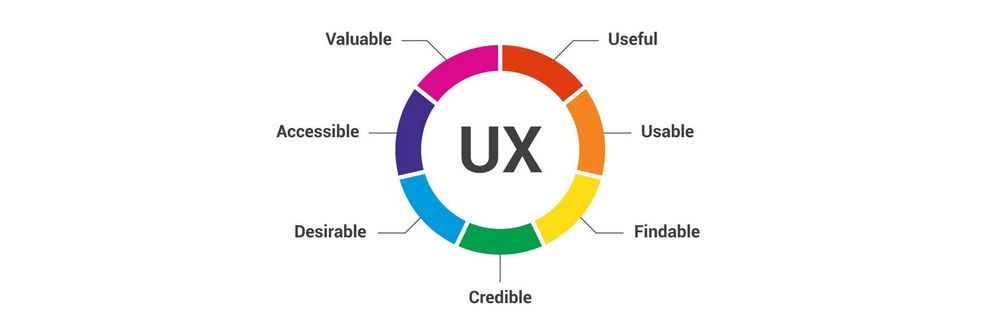

“User or Participant”: As user-centred design (UCD) rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s the terms user and participant came to the forefront of design. A user is still a customer and will still be the recipient of the final outcome of the design process. However, users (at least in user-centred design environments) play a more active role in product and service development.

UCD requires that the user is considered at every phase in a design project and that we, as designers, focus our efforts on making sure that our designs are adapted to users’ wants, needs and limitations.

The term user is widely-accepted in the field of design now. User experience (UX) design, user interface (UI) design, end-users, etc. are all common place terms for designers.

“Adapter or Co-Creator”: In her paper “Scaffolds for Building Everyday Creativity”,Liz Sanders says; “we [designers] are beginning to see them [the people that we serve through our designs] not only as recipients of the artefacts of the process, but as active participants in the design and production process itself. We see that they are capable of adapting products to better meet their own needs.”

That’s a pretty powerful change from consumer or user isn’t it? No longer do we design to involve people in our design process – those people take an active part in that process. When applying UCD we might have asked “lead users” or “early adopters” to gain more insight into our designs but they were still kept very much outside of product and service development.

When our users move into a “co-creation” mind-set they stop being passive consumers and take an active role in working with the design team to create and improve products and services. Adapters and co-creators become partners with the design team and they innovate constantly.

When we look at adapters and co-creators we’re seeing that everyone has creative skills and anyone can adopt a design mind-set. To make the most of these people we need to call on different techniques and methodologies in our design process to value them and their input. UCD involves plenty of group activities and facilitated sessions but to work with co-creators we need to change the way we manage such activities.

There are plenty of major companies using co-creators such as Nike, Lego and P&G. Nike, for example, allows people to design their own running shoes. They can build them in any colour scheme from a wide range of materials for a wide range of functions and they can do it online with expertise in shoe manufacturing required. Nike provides the expertise; the co-creators provide the creative spark.

What about Prosumers?

We need to be a little careful here as there are several definitions of prosumer that exist. In a design context we mean “a customer who helps a company design and produce its products. Prosumer is a word formed from the words ‘producer’ and ‘consumer’”. (From the Cambridge Dictionary)

This is distinct from the idea of “prosumer” which applies to many products where the word is a blend of professional and consumer and indicates a product which is often more complex/able than a traditional consumer model but not as complex/able as a full blown professional product. The Canon 70-D camera is a good example of a prosumer product in this context.

In fact Canon’s entire business model is based on this concept – they have a consumer product typically denoted by 3 or 4 digits such as the 100D or 1200D, then a prosumer product denoted by 2 digits such as the 60D and 70D and then their professional range is denoted by a single digit such as the 1D or 5D.

The term prosumer in a design context was coined by the American futurist Alvin Toffler and it was quickly adopted by many other technology writers. Alvin predicted that the role of producers and consumers would eventually merge as the differences between the two roles began to blur.

It would be fair to say that “prosumer” in a design context is similar to an “adapter” or “co-creator”.

There is a related term too; “prosumption”. This can be found in Dan Tapscott and Anthony D Williams’ book “Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything” where it refers to the creation of products and services by the people who will ultimately use them. (It’s worth noting that Toffler coined this phrase too as a blend of “production” and “consumption”.)

The Continuum Approach

Fischer (2002) indicated a way to examine the differences in consumers and designers in more detail. He posited that we all exist on a continuum and that in some cases we want to be a consumer and that in others we want to be a designer.

He proposed a continuum that ranges from passive consumer to active consumer to end-user to user to power-user to domain-designer to meta-designer.

This seems to be a sensible approach. It also allows for the fact that our roles may change within a design process. For example, you might buy a computer game. Initially you just wanted to be a consumer but you fell in love with the game and started to become involved in the community surrounding it (active consumer).

Then you become involved in community management and are given server privileges (power-user). Finally, you begin to lobby the games designers for changes in expansions, patches and updates.

After a few years… you decide the game is taking up too much of your life. You drop back to being a consumer of new content and take a much less active part in the community.

Fischer’s approach is one where passive consumption may lead to expert adaption and vice-versa. It’s an indicator of the emergence of adaptive design.

The “Makers” Movement

In recent years there’s a new trend that we’ve been able to observe. One in which the customer takes the design lead. It’s often referred to as “the Third Industrial Revolution”.

Jeremey Rifkin shows us that Internet and renewable energy technologies are merging to bring about such a revolution. 3D-Printing, Arduinos, Raspberry Pi, etc. are placing incredibly powerful tools in the hands of anyone who wants to become involved in design.

This is going to bring a huge level of disruption to the world of design. Consumers will become designers and play an even bigger role in society and technological development. User experience designers will need to adapt the tools of their trade and the language they use to accommodate this new era of design.

Of course, for those who do adapt, there’s a huge scale of opportunity to be found for UX designers in this “Third Industrial Revolution” with an ever-growing demand for UX skills to enhance product ideas developed everywhere from the bedroom to the boardroom.

What’s the term of your choice?

It’s important to consider the labels that we apply to the recipients of our products and services. They need to suit the reality of the situation and they need to be fluid enough to change when circumstances call for it.

Customers, users, adapters, etc. are useful to us to help define the relationship between the recipient and the design team. When those labels become restrictive we can switch them out (a customer can become a user, for example, or vice-versa) or create new labels that better define the reality of our situation.

It’s important, however, to ensure that the labels we use are clearly understood and in some cases – we may need to adopt labels from other industries in order for our designs to resonate with recipients in those industries.

References

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Liz Sanders. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved. Img

The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction: Industrial Design

SCAFFOLDS FOR BUILDING EVERYDAY CREATIVITY, Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders. In Design for Effective Communications: Creating Contexts for Clarity and Meaning. Jorge Frascara (Ed.) Allworth Press, New York, New York, 2006.

For the nerds: Cambridge Dictionary Definition of Prosumer