Pricing freelance and business-to-business work (B2B, i.e., business that is conducted between companies, rather than between a company and individual consumers) can be very hard when you’re just getting started. Charge too little, and you’ll starve; charge too much, and you won’t get enough work. You can learn some very simple pricing strategies to help you develop your pricing model. You’ll also find that value-based pricing can help you get to the point of maximum earnings and put you in competition with the biggest earners in your field of expertise.

The thorniest question of them all for many new freelancers and entrepreneurs is, “What do I charge for my services?” There’s some good news and bad news about this. The good news is that it’s easy to set a price for your services—the bad news is that not all services are equal. The really great news is that there’s a way to price your services to beat the market and to maximize your profits. So, let’s take a look at ways to price your work, and let’s save the best until last.

Your Absolute Minimum Price

Before you start setting prices, it’s a really good idea to work out how much you have to earn so that you don’t go broke. While you may be able to live off $1,000 a month in Thailand, you may well find that in London that won’t cover your rent – let alone all your other costs. So, you need to know what your magic number is.

It’s pretty easy to calculate. Add up everything you’re going to spend this year on essential items. That includes things you didn’t have to spend money on when you were working, such as health insurance, computer (and software) equipment for work, office costs (or at least extra heating/cooling, lighting, etc. because you’re now working from home), etc.

Once you have that number, divide it by 48 (this assumes you will take 4 weeks of holiday in a year which will keep you from burning out). That’s how much you need to earn in a week, every single week to pay for all the necessities in life.

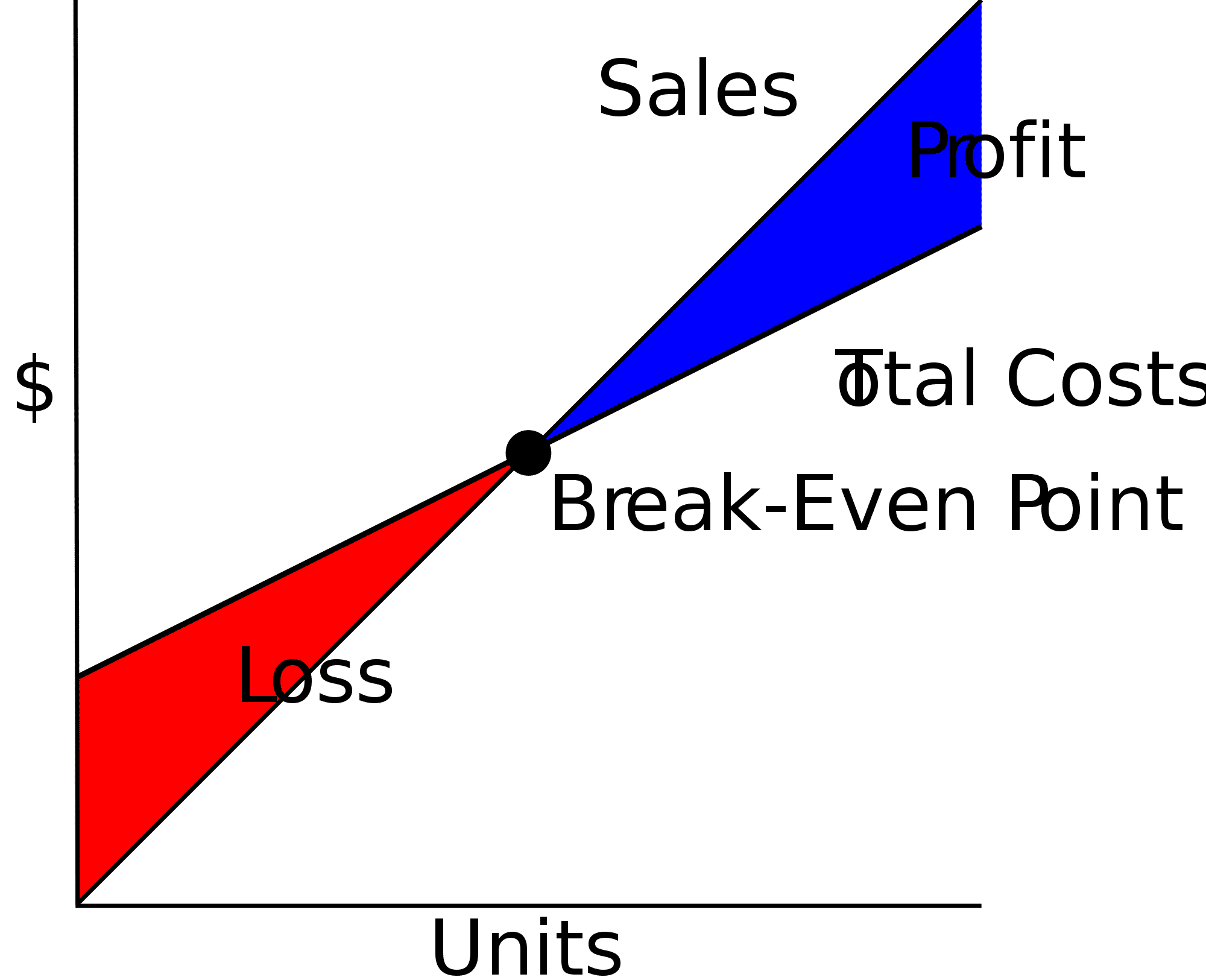

Author/Copyright holder: Nils R. Barth. Copyright terms and licence: Public Domain.

Author/Copyright holder: Nils R. Barth. Copyright terms and licence: Public Domain.

The objective of the minimum price model is to prevent you from making a loss. It specifies your break-even point in business.

How does that translate as an hourly rate? Divide by 20. Hey! Wait a minute—aren’t there 40 working hours (at least) in a week? Sure, you can work as many hours as you like, but the reality is that most first-time freelancers don’t have full diaries and aren’t even getting close to 40 hours during the first year. They’ll still be working 40 (or more) hours a week but doing unpaid work—e.g., sales and marketing and business admin—in the rest of their time. So, take your weekly figure and divide by the 20 hours that you might reasonably expect to average on paid projects in your first year.

That hourly rate is an incredibly useful figure. If you work on a project where you are paid less than that… you are essentially paying the client to work for them. If you’re not making your absolute minimum rate – you’re losing money. Don’t forget that this number only includes essential items, too. Even if you charge at that rate, you’re only working to exist. There’s no budget for fun, no concert tickets, no foreign travel, no DVDs—nothing at all.

Smart freelancers and entrepreneurs know this number so that they can avoid it. You never set your rates at your absolute minimum. Sure, if you have a serious cash flow problem, you might end up working at this rate, but it’s really not recommended. Nobody becomes a freelancer to pay clients to work for them. It doesn’t make sense.

Understand the Market Rate

If you sell your work in a means whereby you don’t actively interact with a client—for example, they can buy a service directly from your website and fill in a form, never contacting you—then the market rate is, perhaps, the best rate that you can attain.

What is a market rate? It’s the rate set down by the professional body which represents your profession in your market. It is not the rate that other people are charging. This is important because there are always people willing to undercut market rates. They’re foolish people. They’re essentially telling their clients, “I’m not worth what the market says I’m worth.”

One thing you learn very early in entrepreneurial life is that the less you charge for a service, the bigger a pain in the backside your clients will be. Professional businesses pay market rates, and they tend to be pretty good clients; if you deliver on your promises, they will be happy. Chancers look to cut corners on pay, and they tend to be ultra-demanding and always trying to shoehorn a little extra “free work” into everything you do.

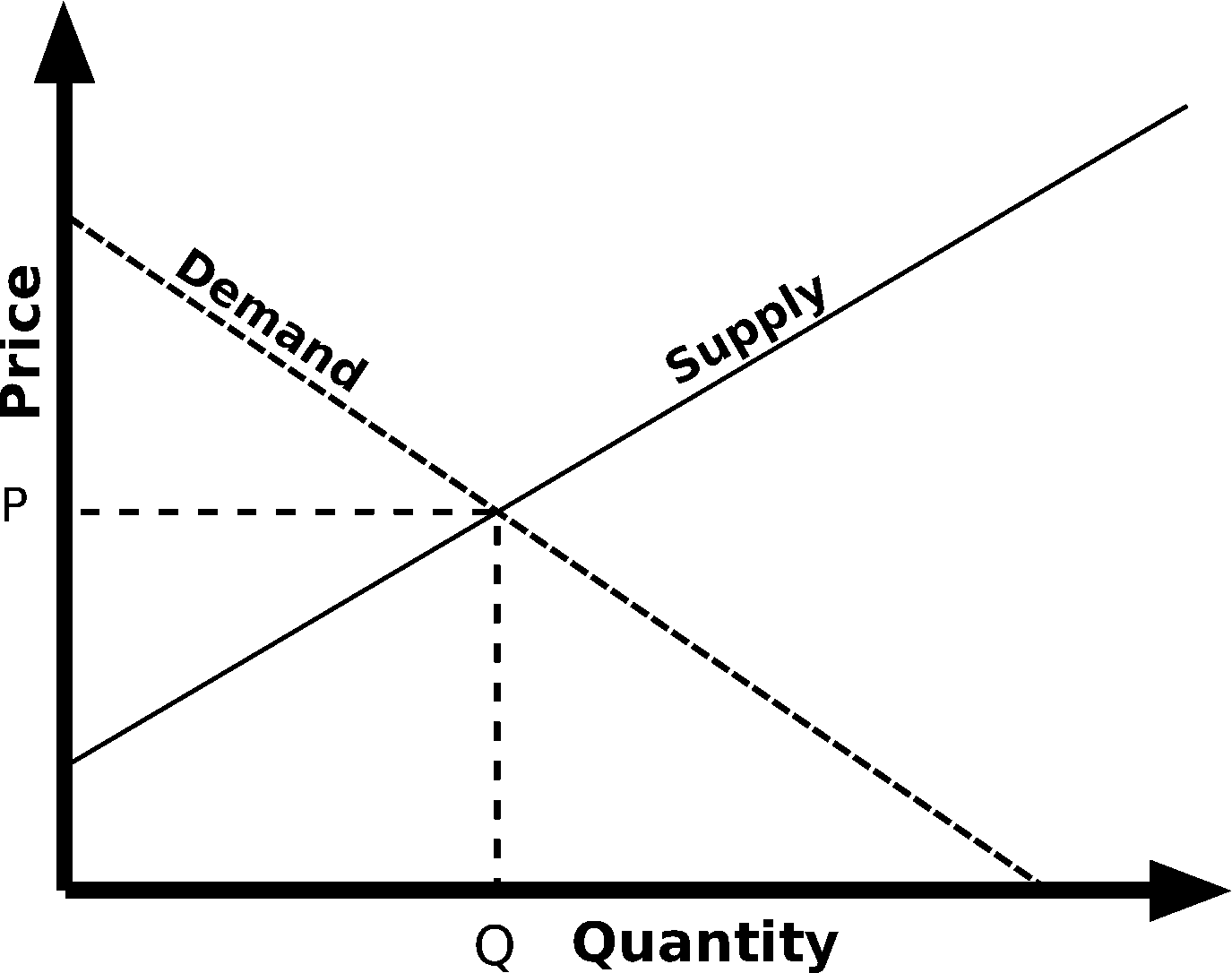

Author/Copyright holder: Dallas.Epperson. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Dallas.Epperson. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

The “market rate” is a function of supply and demand in a perfect world. Unfortunately, the real world isn’t perfect, and it’s best to trust a professional body’s recommendations as to pricing than to believe Fiverr or Freelancer’s recommendations.

How You Find Your Market Rate

Finding your market rate is simply a matter of Googling for your market rate. Market rates are normally expressed as a range, e.g., $50–$100. These tend to reflect the differences in experience between professionals. Someone in early career will tend to be at the bottom end of that rate, and someone with 20 years’ experience at the top of that rate list. However, if you are a newbie who just graduated—but you know for a fact that you’re a perfectionist and better than your classmates—you should take this into account when setting your price, also realising that you’re competing with freelancers with larger portfolios and longer work experience. You want to get your first jobs, but the price should be fair to both you and your future clients.

Market rates are an OK way of pricing your work. You may need to draw the client’s attention to the market rates (send them a link to the professional body) to defend your rate against cheaper rates. But they aren’t the best way to price work, either.

One thing you should be aware of – if the market rate is lower than your absolute minimum price, it will make it hard for you as a freelancer or entrepreneur. You may need to revisit your expenses (and reduce them) or look at learning better-paid skills if you want to freelance in this instance. A business based on the premise that it will always beat the market rate is on shaky ground.

How You Calculate the Price on Fixed Contracts

Most freelancers and entrepreneurs aren’t paid an hourly rate. It’s nice to know your absolute minimum price and your market rate but, by and large, most clients pay for outputs and results (e.g., finished work) rather than an hourly rate.

For a web designer, that might be a payment for launching their website. For a User Experience designer, it might be for a completed piece of research. For a logo designer, it might be when the final logo is complete, and so on…

New freelancers and entrepreneurs have a horrible tendency of underestimating how long work will take them. Why? Because when they were employed, somebody else did a lot of the work before they did their part in the process. A salesman will have sold the work and defined the scope. A legal team will have provided the contracting. Customer care, the support and so on… an employee does one job, and a team picks up the rest of the work.

That was the old regime for freelancers and entrepreneurs. Leaving such employment means becoming a one-person company and doing all this work yourself.

To calculate the pricing on a fixed-price contract, you estimate how long it will take and then multiply by your hourly rate. This is fine—except for that tendency to underestimate the work required.

The best way to start pricing fixed-price contracts is to estimate the amount of work taken and then add 50% to that time. Then, multiply the result by your hourly rate.

You may find that clients want to negotiate on fixed-price contracts, though many times they do not. That rate also gives you some room to negotiate.

Over time, you’ll become much better at estimating the amount of work required for projects, but it’s always better to be safe than sorry. Even when your estimates are generally accurate, a 10–20% increase on an estimate is always a good idea.

The Best Pricing Strategy – Value-based Pricing

Warren Buffet, the billionaire founder of Berkshire-Hathaway knows all about value-based pricing. He says, “Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”

Value-based pricing requires that you talk to your clients and understand their needs. You can’t price based on value, unless you can determine the value to your customers of solving their problems.

How does value-based pricing work? Many people claim to have invented value-based pricing, but the person who probably laid the groundwork is Neil Rackham, the author of SPIN selling, and his take on this is simple.

It is often assumed that people buy based on solving their problems. It is almost certainly true when it comes to small purchases. If you’re cold every time you leave the house, you will buy a jumper, jacket, coat, etc. to solve your problem and create warmth.

Yet, beyond a certain level of minor investment, it turns out that most sales are not closed on the basis of solving a problem; they are based on something deeper – the implications of a problem. What does that mean?

Let’s say your client wants to purchase a new website. The problem—they need a new website. You are capable of building a new website. You could provide a new website based on the market rate cost model.

Yet, it may surprise you to learn that not only could you be charging far too little for your services but that the act of being able to solve the problem is not what will bring you to the sale.

You need to probe deeper. Why does the client need a new website? What’s wrong with the old one?

Then you may find that the actual problem is: “Our conversion rate is lousy—for every 1,000 visitors we get – we get one sale. The industry standard is 3%: that means we’re losing 29 sales in every 1,000 visitors to our competition.”

That’s pretty useful to know, but you still need a little more information. Namely, how many visitors do you get in a month? And what’s the average value of a sale?

Let’s say the customer gets 30,000 visitors in a month and that their average sale value is $2,000. Now, you have a number of value; they’re losing 30 x 29 (the number of sales lost per 1,000) x $2,000 a month. That’s $1.7 million a month! That’s more than $20 million a year in lost revenues!

The implication of the client’s problem, “We need a new website”, is actually, “We’re losing $20 million a year.” Now, how much would you pay to solve a $20-million problem?

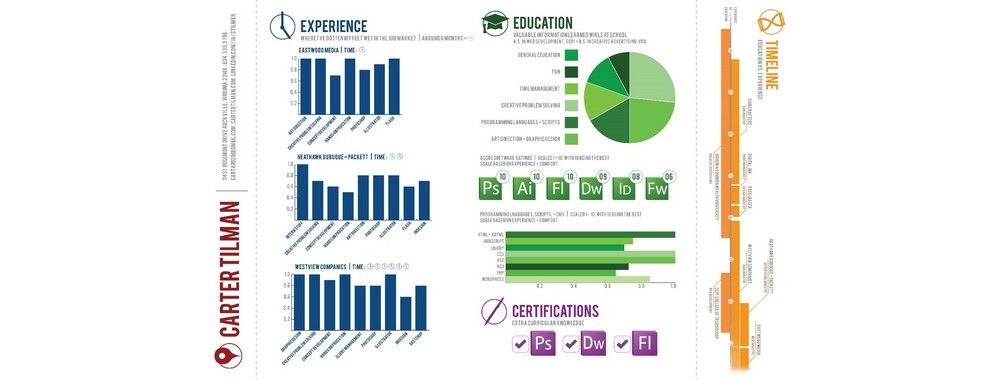

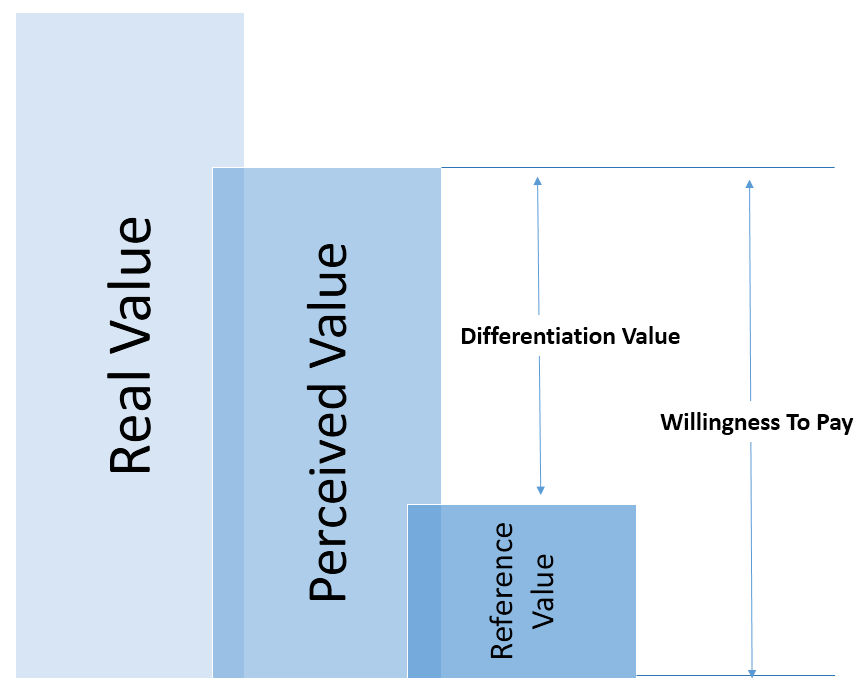

Author/Copyright holder: Asingh86. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

Author/Copyright holder: Asingh86. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

Value is very much a perception-based thing – for your work to have the most value, you need to help your customer understand the real value of the problems they need to fix.

You might have thought about quoting for that website based on hourly rates – but even the best-paid web developers/designers in the world are only paid a small fraction of what this job is worth to the customer. You could charge $1 million for that job, and the customer is going to see a $19- million return on their investment (at least, that’s the theory).

Value-based pricing lets you step beyond the hourly rate model. You prices are dictated by the value that your solution is going to create for the customer. The example above is a touch extreme (and it’s likely that a website that created that much value might require more than one team member to implement), but it happens every single day.

By examining a client’s problems and finding out what the implications of not solving that problem are, you can price your services based on the value of the solution. A client may feel that they need a new website, but they may also not see solving that problem as a priority. However, a client losing $20 million a year will see solving that problem as a priority. Their business revolves on a financial axis—their awareness as to the true problem is key.

You may be thinking that your clients will already know the value of solving their problems – but they rarely do. Most clients are busy people, and they have dozens of issues on their plates. It’s not that they can’t follow the thought process above; it’s that they rarely have time to do so in amongst the hectic nature of their lives.

When you learn these basic sales skills as a freelancer or entrepreneur, you can help a client think through their problems and show value. This way, you will close sales and for much better margins than your competitors who only consider time estimates on projects.

One last thing on value-based pricing—sometimes, this process will reveal that the client’s need isn’t actually a need at all. The cost of doing nothing will turn out to be minimal, and the solution is not a priority. That’s OK, and it’s worth remembering that, ethically, you want to add value to your customer’s bottom line. Taking on projects that don’t provide value will, in the long term, damage your professional reputation. You want to create satisfaction or a “wow” factor, not be a hanger-on.

If you encounter this scenario, explore other areas where you might be able to add value for the client, or, if you cannot, walk away. The client will respect you for this, and you may find that they become an important source of leads in the future. People are very good at recommending suppliers that they perceive as trustworthy even when they don’t close the sale.

The Take Away

You have to know what your absolute minimum price is as a freelancer or entrepreneur. It’s the rate that you never want to go below because, in essence, it’s a rate where you effectively pay the client to do their work. You can’t manage a business on that basis. You’d end up becoming a charity for unscrupulous clients.

Market rate pricing is a fair strategy for many freelancers and entrepreneurs. Charging below market rates is not a great business model.

Stack it high and sell it cheap works for Walmart because they don’t make the products, and there are no limits on the amount of products they can sell.

Author/Copyright holder: Patrick Denker. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0

Author/Copyright holder: Patrick Denker. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0

Whatever you do, do NOT fall for the “stack it high, sell it cheap” model. There’s only one of you – that makes you a limited resource. You cannot sell 400 hours a week’s worth of your time.

Start-ups only have themselves to do the work (and outsourcing work below your market rate is incredibly tough – quality suffers)—they are a finite commodity. Selling your services at a market rate allows you to earn an appropriate level of reward when compared to your peers.

However, value-based pricing is the way to maximize your returns. Fully understanding a client’s problem in financial terms allows you to charge for your services based on the value that you create. This can often turn out to be many times what you would charge at market rates. It also leads to happier clients—you’ll have transformed your service from “supplying stuff” to “creating value”.

References & Where to Learn More

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Peter Blanchard. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

Neil Rackham, SPIN Selling, 1996