What Are Wicked Problems and How Might We Solve Them?

- 1.2k shares

- 2 years ago

Systems thinking is an approach that designers use to analyze problems in an appropriate context. By looking beyond apparent problems to consider a system as a whole, designers can expose root causes and avoid merely treating symptoms. They can then tackle deeper problems and be more likely to find effective solutions.

“You have to look at everything as a system, and you have to make sure you're getting at the underlying root causes.”

— Don Norman: Father of User Experience design, author of the legendary book The Design of Everyday Things, co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group, and former VP of the Advanced Technology Group at Apple.

See why systems thinking helps prevent wasted time and resources on the wrong problem.

Apple's headquarters at Infinite Loop in Cupertino, California, USA. by Joe Ravi (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

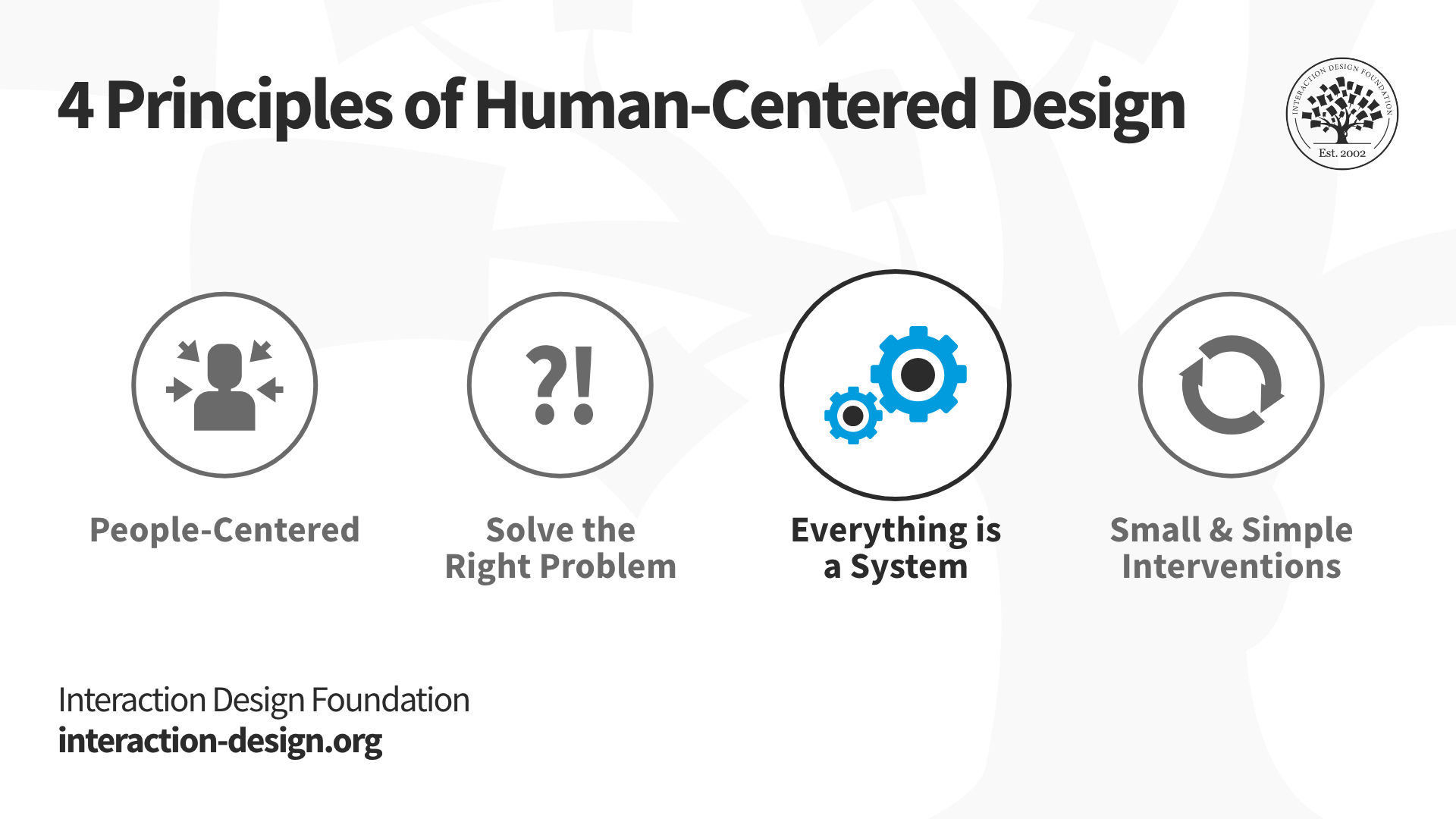

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AApple_Headquarters_in_Cupertino.jpg Systems surround us, including within our own bodies, and they’re often highly complex. For example, that’s why doctors must know patients’ medical histories before prescribing them medicines. However, our brains are hardwired to find simple, direct causes of problems from the effects we see. We typically isolate issues we notice by considering how to combat their symptoms, since we’re more comfortable with “If X, then Y” cause-and-effect relationships. Cognitive science and usability engineering expert Don Norman identifies the need for designers to push far beyond this tendency if they want to address serious global-level problems effectively. That’s why systems thinking is not only an essential ingredient of 21st century design but also a principle of human-centered design.

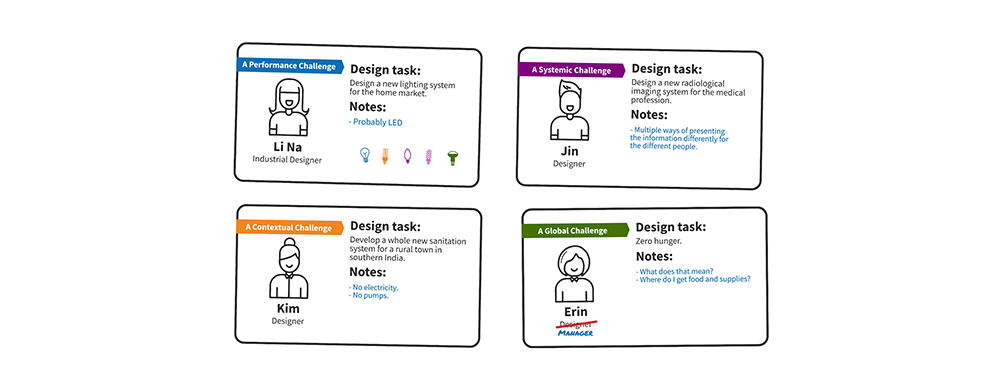

The concept of systems thinking emerged in 1956, when Professor Jay W. Forrester of MIT’s Sloan School of Management created the Systems Dynamic Group. Its purpose was to predict system behavior graphically, including through the behavior over time graph and causal loop diagram. For designers, systems thinking is therefore vital to tackling larger global evils such as hunger, poor sanitation and environmental abuse. Norman calls such problems complex socio-technical systems, which, like wicked problems, are:

● Difficult to define.

● Complex systems.

● Difficult to know how to approach.

● Difficult to know whether a solution has worked.

The danger of not using a systems thinking approach is that we might oversimplify a situation, take problems out of context, treat symptoms and end up making matters even worse. Norman considers electric vehicles an example of an apparently good solution (to pollution) that can obscure what should be the real focus. If the fuel source that generates their electricity comes from coal, etc., it defeats the purpose and, worse, could cause even more world-damaging pollution, especially if so much electricity perishes between the generating source and the consumers’ power supply.

© Daniel Skrok and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Systems thinking is also the third principle of humanity-centered design; therefore, integrate it within this approach:

● Be people-centered. Spend a long time living among the people you want to help, to understand the true nature of their problems, their viewpoints and solutions they’ve tried. For example, a village’s crops might be failing even though the water source seems adequate.

● Solve the right problem. Closely examine the factors driving the people’s problems. Try the 5 Whys approach. E.g., the soil is damp enough, so might it be exhausted of nutrients? Or does it contain toxins? Why? Sewage? If not, what then?

● Consider everything as a system. Now, leverage systems thinking to untangle as many parts of the problem(s) as possible. Complex socio-technical systems such as (potential) famine demand hard investigation and working alongside others: principally, the community concerned; so:

Keep consulting the community leaders for their insights into the problems you uncover.

Evaluate the feedback loops. E.g., the collected clean water from a small stream and secondary well should be enough to irrigate the village’s few fields. The people seem to be doing things correctly: using pipes and a small ditch they’ve diverted from the stream and enclosed using plastic sheets strung over metal frames. The soil is adequately fertilized; the farmers water after dusk (operating taps and a sluice from the tunnel). Still, the problem persists.

Dig past the apparent problems to root causes. E.g., thinking of the village’s irrigation system as a system, you notice it’s not the amount of water or soil quality. The water is slightly too hot — due to the dark-colored plastic pipes and the black plastic sheeting of the improvised tunnel — for the crops to handle.

● Proceed towards a viable solution using incrementalism:

Wait for the opportunity to do a small test of the small-scale solution you’ve co-created with the community. E.g., fortunately, here, a good solution involves just lightening the color of the irrigation system to reflect sunlight. The village has enough white paint for the pipes, and you collect white sheeting and tarpaulins to cover the stream tunnel.

If it’s successful, evaluate how successful; then adapt and modify it or repeat it several times until you fine-tune a sustainable solution. E.g., fortunately, you just need to find more light-colored tarpaulins.

Overall, systems thinking is about reframing a problem to expose its addressable underlying causes. Thinking broadly, you can deduce real problems and stop to consider potential solutions with (e.g.) design thinking. That’s how community-driven projects — and people-centered design — arrive at inventive, economical and culturally acceptable best-possible solutions.

Use the 5 Whys method to help you find the root causes.

Ready to shape the future, not just watch it happen? Join the Father of UX Design, Don Norman, in his two courses, Design for the 21st Century and Design for a Better World, and turn your care for people and the planet into design skills that elevate your impact, your confidence, and your career.

Systems thinking differs from traditional UX approaches by shifting focus from isolated user interactions to the broader ecosystem surrounding a product. While traditional UX often zeroes in on optimizing specific touchpoints—like a button or a user flow—systems thinking looks at how all parts of a product, user, and environment connect and influence one another.

Systems thinking helps designers anticipate ripple effects across teams, technologies, and social contexts. For example, changing one feature might improve a workflow but negatively impact user trust or data flow elsewhere. Designers using systems thinking map these relationships and design holistically.

This mindset is essential in complex environments like healthcare, finance, or smart cities—where user experiences span multiple platforms, policies, and people.

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

UX designers should learn systems thinking because it helps them design for the whole and not just the parts—and the whole is far more than the sum of the parts. Products today exist in complex environments—across devices, user groups, organizations, and real-world contexts. Systems thinking trains designers to see patterns, relationships, and feedback loops that traditional UX might miss.

By thinking in systems, designers can anticipate unintended consequences, solve root causes rather than symptoms, and create solutions that scale. It helps teams align across departments, too, especially when UX decisions impact data, operations, or customer service.

For example, a small design tweak in a healthcare app might ease user flow but could disrupt data compliance or medical workflow. Designers who use systems thinking can help avoid these disconnects by focusing on the full ecosystem.

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

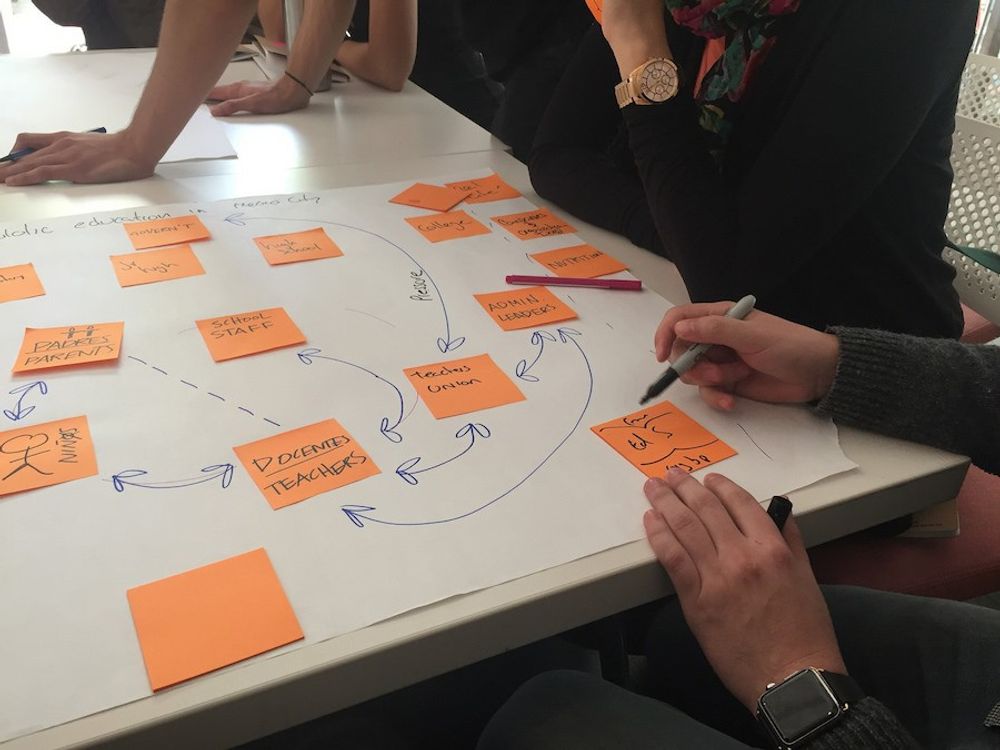

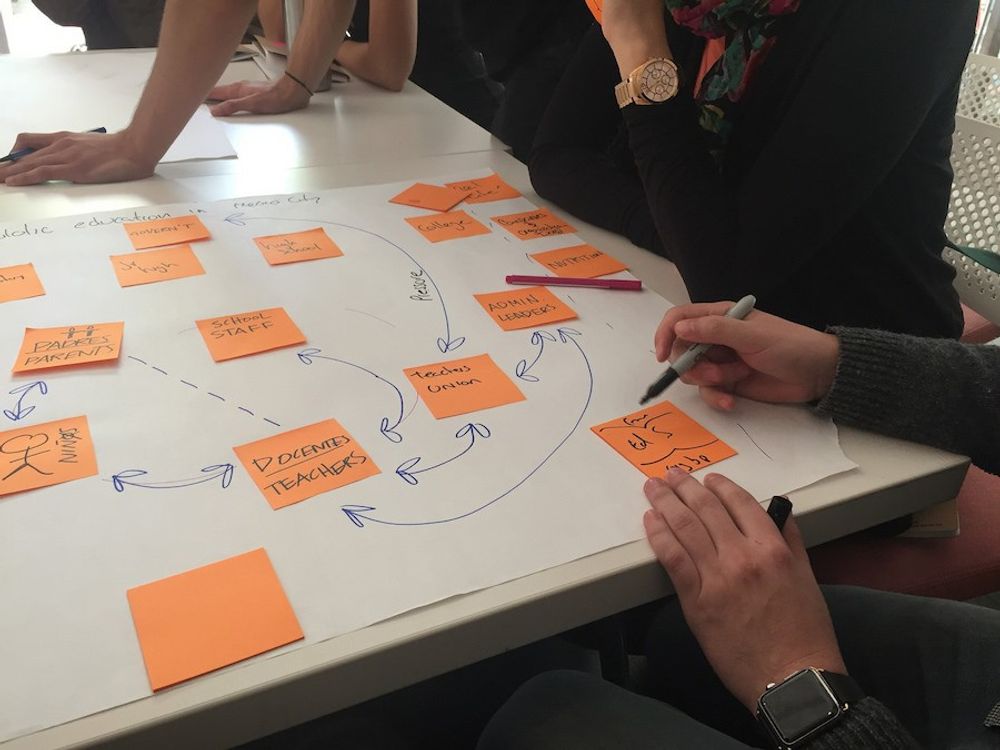

To apply systems thinking to digital product design, start by mapping the ecosystem around your product. Look beyond the screen—and consider users, teams, technologies, policies, and social dynamics. Use tools like system maps or causal loop diagrams to visualize how parts influence one another over time.

Next, identify feedback loops. For example, if users skip onboarding, does that cause support tickets to spike? If so, that’s a signal for systemic refinement. Frame problems in terms of relationships, not isolated touchpoints.

Co-create with cross-functional teams—systems thinking thrives on multiple perspectives. And always zoom in and out: design the micro-interactions, but never lose sight of how they connect to macro-level goals.

Firms like IBM and SAP use this approach to build scalable, resilient, and user-aligned systems.

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

Systems thinking helps you understand user behavior by revealing the broader systems that shape it. Instead of just asking what users do, systems thinking uncovers why they do it—by examining relationships, influences, and context.

For example, if users abandon a signup flow, a “traditional” UX approach might blame the form. However, systems thinking might reveal upstream issues—like confusing pricing, social distrust, or inconsistent messaging across touchpoints. By mapping these interconnected parts, you uncover root causes instead of surface symptoms.

It also helps you track how user behavior evolves over time. Behavior doesn’t happen in isolation—it reflects policies, feedback loops, and interactions with other people or tools.

In short, systems thinking gives you a dynamic lens for user behavior, which leads to smarter, more holistic design and designs as a result.

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

Feedback loops play a key role in UX design as they help systems learn and adapt based on user input they get. A positive feedback loop reinforces user behavior—like when Duolingo celebrates a streak, encouraging users to keep coming back. A negative feedback loop, by contrast, corrects or balances behavior—such as when a system warns users before deleting data.

Well-designed feedback loops keep users informed, in control, and emotionally engaged. They’re not just about function—they shape how users feel during and after an interaction and as such are vital to the overall user experience.

In systems thinking, feedback loops reveal how small actions ripple across the user journey. Designers can identify where experiences break down, or where friction becomes frustration.

Smart UX uses feedback loops to align product behavior with user expectations—and create designs that improve over time.

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

To map complex user flows using systems thinking, begin by identifying every actor, system, and touchpoint involved—not just screens or features. Then, visualize how these parts interact over time using tools like ecosystem maps, system maps, or causal loop diagrams.

Unlike linear user flows, systems-based maps account for feedback loops, delays, dependencies, and multiple user paths. For example, a user action in one interface might trigger back-office workflows or third-party integrations—and systems thinking helps you trace these chains clearly.

Collaborate across departments to include operational and technical perspectives. This gives you a full picture of what supports, influences, or disrupts the user journey.

Think like a service designer: zoom out to understand the whole system, then zoom in to optimize the flows that matter most.

Watch as CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains important points about how to map the ecosystem of a service design:

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

To find unintended consequences in design systems, use systems thinking to trace cause-and-effect relationships across the product’s ecosystem. Start by asking: “What happens after this feature works as expected?” Then map ripple effects, not just user flows. Look for feedback loops—are you reinforcing harmful patterns, like dark patterns or addictive loops?

Tools like causal loop diagrams help visualize side effects and delays that might not appear in a prototype or sprint review. Engage cross-functional teams—engineers, policy experts, support staff—to uncover blind spots you might miss from the design view alone.

For example, adding a “streak” feature might increase engagement but cause anxiety or burnout for some users. Systems thinking helps surface these contradictions early.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

To use systems thinking in UX research, expand your scope beyond individual users and screens. First, identify the system: who are the stakeholders, what external factors shape behavior, and how do different elements interact over time?

Instead of focusing solely on isolated pain points, use tools like ecosystem maps, stakeholder maps, or causal loop diagrams to trace patterns, feedback loops, and indirect influences. For instance, a usability issue might stem from policy constraints or backend limitations—not just poor UI.

Interview across roles and departments to capture how different parts of the system perceive the same experience. You’ll likely uncover far deeper insights by studying what happens between touchpoints—not just at them.

Systems thinking helps UX researchers reveal root causes and design insights that resonate far beyond the interface.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

To bring systems thinking to a UX team or organization who aren’t familiar with it, start with shared language and visuals. Host a workshop using real product challenges to map out systems diagrams, feedback loops, or stakeholder maps. This hands-on approach helps teams see how systems thinking reveals hidden patterns and interdependencies.

Frame it as a complement—not a replacement—for existing UX practices. Show how it adds depth to research, aligns cross-functional teams, and prevents unintended consequences.

Use small pilot projects to demonstrate impact. For example, apply systems thinking to redesign a user journey across departments or touchpoints. Share outcomes widely and invite others to build on the approach.

Organizations like IBM and Salesforce have embedded systems thinking by creating shared toolkits and embedding systems-minded roles in UX teams.

Watch as UX Pioneer and the Godfather of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about systems:

Enjoy our Master Class Systems Thinking for Designers: A Practical Guide with Erik Stolterman, Author and Professor in Informatics at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Pourdehnad, J., Wexler, E. R., & Wilson, D. V. (2011). Systems & design thinking: A conceptual framework for their integration. University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons.

This paper by Pourdehnad, Wexler, and Wilson explores the conceptual integration of systems thinking and design thinking. It argues that addressing today’s complex and evolving challenges requires blending the holistic, interconnected perspective of systems thinking with the creativity and user-centered approach of design thinking. The authors propose a combined framework that incorporates the philosophical underpinnings of both approaches to tackle complex social systems more effectively. Particularly relevant for UX and organizational design, this work highlights how such integration can improve decision-making, innovation, and the sustainable implementation of solutions. It’s influential for those developing methodologies to address complexity in user experience and design strategy.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer (D. Wright, Ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing.

Thinking in Systems is a foundational text by environmental scientist Donella Meadows, edited posthumously by Diana Wright. The book introduces systems thinking—an approach to understanding complex issues by analyzing how their components interact through feedback loops and systemic behaviors. With accessible language and everyday examples, Meadows unpacks concepts like reinforcing loops, system resilience, and time delays. She emphasizes that many global challenges, from climate change to economic inequality, are system-based problems. This book is lauded for translating complexity into clarity and remains essential for leaders, educators, and designers seeking sustainable, big-picture solutions in an interconnected world.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice Of The Learning Organization. Doubleday/Currency.

Peter M. Senge’s The Fifth Discipline redefines how organizations can cultivate continuous learning and adaptability. By introducing five core disciplines—personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, team learning, and systems thinking—Senge establishes a blueprint for building "learning organizations" capable of sustained innovation and resilience. The book is particularly notable for elevating systems thinking as the “fifth discipline” that integrates the others into a cohesive framework. It has become a foundational text in organizational development, offering strategies for long-term success in a complex, changing world. Senge's blend of theory and practical advice makes it indispensable for leaders, educators, and change-makers seeking transformative growth.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Systems Thinking by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Systems Thinking with our course Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group, and former VP of the Advanced Technology Group of Apple.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!