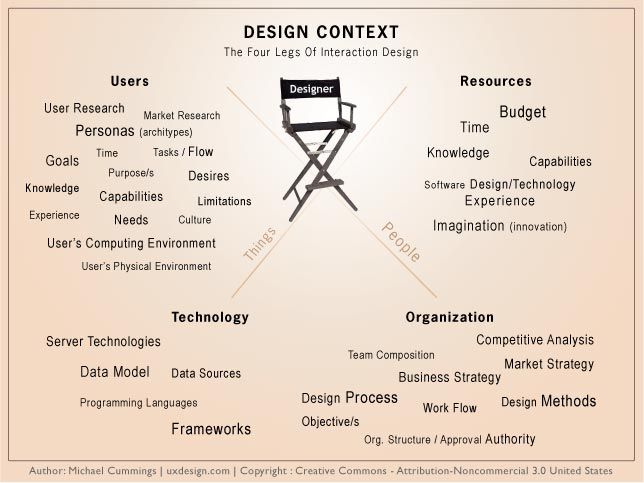

Contextual design is a reflection of the idea that no design exists in a vacuum. That one technology or perhaps system will interact in a much larger context; one of its environment and that that environment will not necessarily remain static (unchanging). Thus contextual design places a design in “context” and seeks to maximize its usefulness.

There are some key principles of contextual design:

System Design Should Support/Extend User’s Current Work Practices

This should be obvious; if you want design to fit easily into a user’s context – it shouldn’t be looking to shake up their world but rather to complement it. If you can do that; then you are a long way to getting your product accepted and liked by a user. If you can’t… well the user may prefer to throw it out the window than take the time to grips with it.

Expertise Does Not Equal the Ability to Articulate Current Work Practices

This is rather less obvious. People tend to be experts at the things that they do regularly; “their current work practices”. However, holding expertise does not necessarily make them experts at communicating what it is they do. Many of us struggle to articulate the concepts, practices and ideas we are most familiar with. This means that the contextual designer must observe those work practices rather than relying on oral accounts of what is being done.

Design Must Take Place in Partnership with Users

If you engage with users in the design phase there is a substantially higher chance that you will design products that suit those users. This is the key concept of all design disciplines; the idea that the user’s experience is critical to developing great products and systems. Contextual designers should not approach their users with forms to fill and boxes to tick but instead should adopt a larger curiosity that involves asking users what they want, need and feel rather than making assumptions on any of these details.

Good Design Should Be Systemic

Even the greatest idea in the world can fall flat on its face if it fails to consider the larger system in which the user operates. Design features must conform to the larger design aesthetic; a giant sized purple button in the middle of your iPhone’s case, for example, is simply not going to work for the iPhone owner – no matter how wonderful the effect of pushing that button. Designers should be looking for coherence in their systems rather than to break the mould.

Design Depends on Explicit Rendering

If you build it, they will come. Well… not always but you can be certain if you build something that people can tell you if they’d come or not. Contextual design requires sketches, prototypes, working models, etc. designers can work with users and vice-versa easily and simply from this perspective. They can talk about what they like and what they don’t and the design can be revised until it finally delivers on its promise.

Of course, these principles apply widely to many design disciplines as well as to contextual design. If you want to better understand contextual design; why not check out our complete text by Karen Hotzblatt on Contextual Design – it’s completely free to read it online.

Header Image: Author/Copyright holder: PionSoft LLC. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved. Img