We all like to think that we are consistent; it allows us to feel that we are always ourselves and thus dealing with the universe in a way that is fair and rational. However, under the surface, we’re not very consistent. We adapt to our circumstances, and, as we do so, we become less consistent, and then we rationalize that inconsistency into a new story that enables us to feel consistent. Why does this matter to you as a designer? You may be able to change people’s views of themselves through your designs. Let’s find out how you can show them a magic mirror, shall we? Read on and see.

Can You Change Someone’s View of Themselves?

The way we view ourselves enables us to make decisions that feel consistent. This keeps our new brains happy (the rational component of the brain; the old brain deals with instincts and the midbrain with emotions) because it’s important to be consistent for that part of the brain to feel rational (even if we’re not all that rational about our decisions).

This is useful to know because if we can tap into someone’s internal story, we can sell our products or services more easily to that person. However, it also raises a question. What if our product or service doesn’t match someone’s internal story? Can we still sell it? Or are we permanently precluded from dealing with that person?

Two Answers – Neither of which is Perfect

There are two answers to that question. Firstly, we may be able to tap into a different story. We have many different self-images, and the one we tap into could overrule other self-images that might conflict with what we want at that moment in time.

However, if none of someone’s current personal stories (self-images) match our product and our story, it’s still possible to get someone to buy from us.

Secondly, however, it’s not 100% satisfactory, because while you can get people to move outside of their current personal stories, they’ll only move a little way—at least at first.

So, if you’re trying to get people to buy a new camera, for example, despite all of their current personal stories being aligned with buying a second-hand camera, you may be able to sell them a low-cost new camera (which represents little risk). Still, it’s unlikely you’ll get them to buy a very expensive top-of-the-range model (that’s too far removed from their current stories).

Author/Copyright holder: Canon Australia. Copyright terms and licence: Fair Use.

You may change someone’s story to sell them a camera, but you’re unlikely to make a dramatic change to their story. So, such people may move from a second-hand camera to a cheap new one, but they probably won’t buy a $5,000 camera.

It Gets Better, Though

There is a silver lining here. Once people move outside of their personal stories and do something which is incongruent with their stories, something changes. These folks will begin to rewrite their stories so as to accommodate their decisions. Why? Well, it’s that new brain in action again.

We can see elsewhere how the new brain is not as rational as it might want to be. It’s better at coming up with rational explanations for why we did something than it is at forcing us to be rational. It will wait until after the fact (and after the decision gets made) before it jumps in with a rationale for it—anything, as long as it doesn’t get caught trying to justify a decision with “because I felt like it”. So, if we step outside of our comfort zones, the new brain comes to the rescue and rewrites the story until we feel consistent again.

As such, if you can make a minor change, such as selling a low-cost new camera, you may be able to effect other minor changes in the future (the next purchase might be a brand new mid-range camera) and—over time—combine those changes in order to make a major change (finally selling that top-of-the-range model to your customer).

Author/Copyright holder: Pixabay. Copyright terms and licence: CC0

The “silver lining” of change is that small changes can add up to big changes if you’re patient enough to wait for them.

It’s Been Proven

Jonathan Freeman and Scott Frazier conducted some research into the way we can change people’s perception of themselves over time. In 1966, they ran an experiment that went something like this:

They approached people and asked them if they’d mind having a “Drive Carefully!” sign mounted in the gardens of their properties so that drivers could view them from the road. The sign itself was large and, frankly, ugly, and not the kind of sign that householders are generally keen to have in their gardens.

Author/Copyright holder: Katy Warner. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

Would you be keen to have a no-speeding sign put in your garden? You might change your mind if you signed a petition against speeding or had a no-speeding sign in your car.

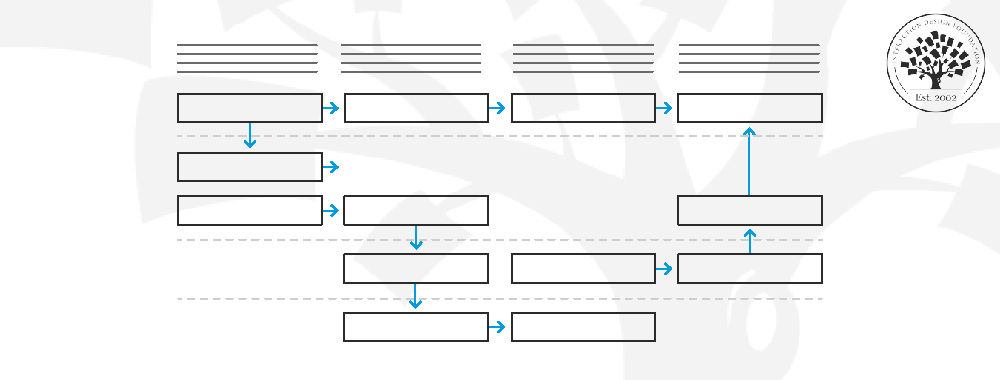

They split the target group into three sections:

Section A would be asked if they would have the sign in their gardens with no other activity prior to that.

Section B would be asked to display a small version of the sign in their vehicles; three weeks later, they’d be asked if they’d have the big sign in their gardens.

Section C would be asked to sign a petition to “Keep their neighborhood safe!”; three weeks later, they’d be asked if they’d have the big sign in their gardens.

The rules also required that a different person asked the second question to Sections B and C from the person who had asked the first question. This was to eliminate a possible experimental bias where the person said ‘yes’ to the second request because he or she had bonded with the person who had asked the first question.

What happened?

Well, in Section A, the majority of people said ‘no’. Only 20% agreed to display the sign. In Section B, the majority said ‘yes’ and nearly 76% agreed to display the sign after they’d been exposed to the small one. In Section C, the majority still said ‘no’, but nearly 46% said ‘yes’ to the big sign after signing the petition.

The small changes in people’s personal stories had a powerful effect in the long run. Those exposed to the most similar change made the biggest swing towards the bigger change. However, even a seemingly unrelated change brought measurable benefits.

“The man who moves a mountain, begins by carrying away small stones.”

—Confucius, Chinese philosopher.

The Take Away

Small changes in people’s personal stories can have a dramatic effect on their behaviour. If you can get people to make small changes in the short term, you can often get them to make bigger changes in the long term. Therefore, as a designer, you may be able to encourage those small changes prior to offering a large change. Knowing your target audience is key here, as is appreciating what the product or service on offer from the organization you’re designing for means to them. By edging your way carefully regarding how the items on sale speak to your users, you can use some skillful manoeuvres to bring them round as conversions.

References & Where to Learn More

Freedman, J. L. & Fraser, S. C. (1966). “Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 195-202.

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Symode09 . Copyright terms and licence: Public Domain.