We often talk about creating positive emotions through design; we look to make clients happy and users comfortable, etc. but rarely do we talk about making them afraid. Of course, unless you’re selling horror movies, you probably won’t want to terrify your clients; however, there is a good argument for tapping into basic fear in your designs in order to improve sales. Accessing this vein of thought will allow you to infuse your work with greater chances of success as you drive users to take action.

A Walk in the Woods

Picture yourself walking through a jungle. It’s hot… and you can hear the cries of birds and monkeys in the distance. You’re a little nervous, and you know that the jungle can be a dangerous place, but, mostly, you’re exhilarated by the scenery and the natural beauty. Then, out of the corner of your eye, you see a flash of orange and then a flash of black streak past a tree.

At this point, it’s likely that your first instinct is to think “Tiger!”, followed by a rush of adrenalin, and then the urge to run away as fast as your legs will carry you.

You haven’t actually confirmed that what you’ve seen is a tiger. However, what’s happened is that your old brain has made a decision based on the data you have. If you waited until you could confirm whether the animal was a tiger, and if it was a tiger, there might be a higher chance of your becoming its breakfast.

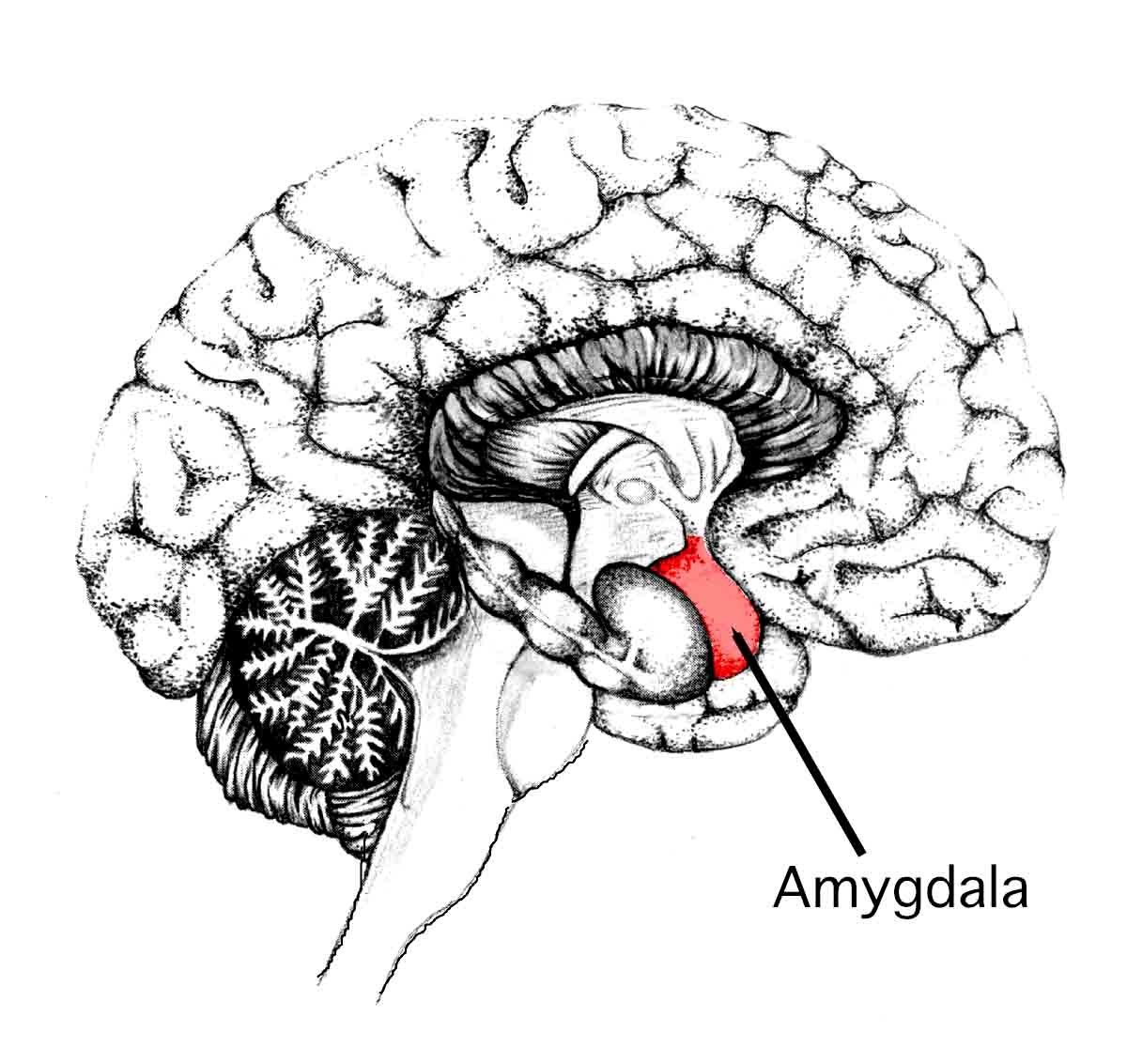

The Amygdala

The amygdala, as you might remember, is the part of your brain that deals with visual information. The amygdala—or, more precisely, amygdale, as we have two of them in our heads—is designed for pattern recognition. So, if you see something that looks somewhat like a tiger, it immediately lets the old brain know. This is also true if, for example, you were to glance at a stick on the ground in our jungle and mistake it for a snake.

Author/Copyright holder: Sgerstenberg. Copyright terms and licence: CC0 1.0

The amygdala is the part of the brain that processes visual data and draws conclusions based on that data—at lightning speed.

Your brain wants you to be safe. It’s willing to take some shortcuts so as to increase the odds of safety and that means, every now and again, it’ll make up data rather than wait for the complete picture. It lives and breathes the maxim of “better safe than sorry”, always erring on the side of caution, and always fearing the worst.

Fear is a Powerful Motivator

Fear is programmed into the old brain—and that’s the part of our brain that deals with instinct. Fear can be a powerful motivator to do something… or not to do something.

What Are People Afraid Of?

“The emotional tails wags the rational dog.”

—Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize-winning economist

Today, you have a hard decision to make. It’s your best friend’s wedding, and you’ve been asked to play an important role. Unfortunately, a prospective client with a potentially huge budget has hit town today, too. They want to meet today and, if you can’t do that, they’ll go with your supplier. The only time slot they have available happens to be right in the middle of your friend’s wedding ceremony – what do you do?

Most people choose their friend. They choose their friend because they fear losing something they have more than they fear losing something they don’t have (the client’s business). If you cut and run on your friend’s wedding, they’re probably not going to speak to you again, and you have no guarantee that the meeting with the client will result in getting their account, anyway. So, going against nature could find you losing on both fronts.

Author/Copyright holder: Charuti Latha,Deepak. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

If you miss your friend’s wedding, you’re likely to create an unhappy couple.

The thing that we are most afraid, normally, is losing what we already have.

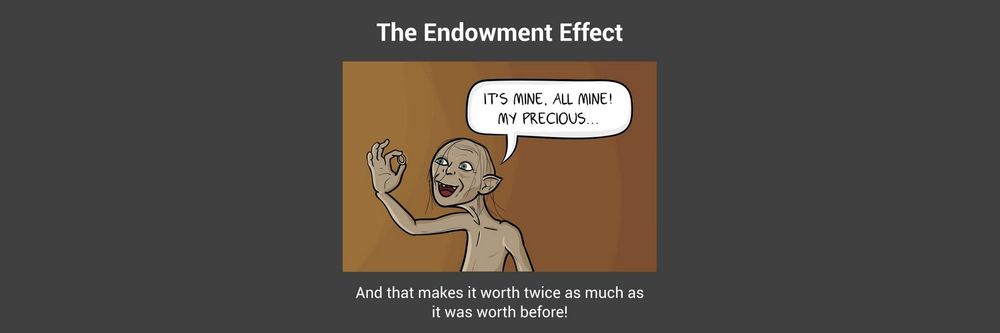

The Endowment Effect

This phenomenon is an example of the endowment effect, a cognitive bias, which was coined by Richard Thaler, the economist, in the 1990s (though the effect had been observed to some extent in other experiments in the 1960s). Working with Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel prize winner, and Jack Knetsch, another economist, they determined that if someone was given a mug and then offered to sell it or trade it for an equally valued item, they typically demanded twice as much as the value of a mug they now owned than they had valued the mug at when they did not own that mug.

Author/Copyright holder: Public Domain Pictures. Copyright terms and licence: Free to Use

We value a mug that we own at twice the value we attribute to a mug we don’t own.

Daniel Kahneman proposed that this is because human beings are loss-averse and that giving up something you own is a form of loss.

From a Design Perspective

If you can convince users of their ownership of something, they are more likely to resist losing ownership of that item. For example, if you give someone a free trial of your product, they are more likely to pay for it at the end of the free trial. Why? If someone were not to pay for the product, that would mean surrendering it and thus losing it.

The Take Away

People are loss-averse. If they feel that they own something, they will be less willing to give it up than they will be to take a risk on doing something new. This segment of human nature manifests itself in all sorts of forms, from fears of losing friends by making bad choices to trading items in our possession for other ones. This fear throws up an ideal setting for you to use a superb strategy in design. You can cater to this behaviour by offering free trials to enable users to take “ownership” of a product before asking them to pay for it. Having enjoyed the convenience it has to offer for a little while, the chances are far greater that they will prize this thing that they feel they “own” so much that they go ahead and actually make it their own by paying for it.

References & Where to Learn More

Kahneman, Daniel; Knetsch, Jack L.; Thaler, Richard H. (1990). "Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coarse Theorem". Journal of Political Economy 98 (6): 1325–1348

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Honzasoukup. Copyright terms and licence: Public Domain