In the developed world, we have the benefit of choice; if a product fails to provide us with a positive emotional experience, we can simply look for an alternative. Consumerism is now more cutthroat than ever; no sooner has one product been released, another, similar product appears in its place on the shelf. So as to ensure survival, businesses and designers must not only develop products that are effective, but they must also enhance positive aspects of the user experience and limit or eliminate negative aspects of the user experience. At the root of both these achievements is an understanding of who the users are, where and when they will use the product, and how the product is going to be used.

Human emotions can generally be divided into two groups: positive and negative. If you just take a moment, try to think of as many emotions as possible and divide them into 'positive' and 'negative' emotion groups. You probably thought of the most common and perhaps basic human emotions, such as happiness, sadness, and fear, with the former classified as a positive emotion and the latter two classified as negative emotional states. However, over the course of our lives we experience a huge array of emotional states, some of which are difficult to bracket entirely in one category or the other. In fact, some languages have untranslatable words that describe mixtures of emotions (e.g., in Greek, “harmolipi” – a mixture of happiness and sadness at the same time, or in Spanish, “duende” – an emotional response to art which may involve crying or smiling, or both at the same time!). Emotional states are generally the result of one of the following: disposition (e.g., depression, which tends to color how one feels about everything in life), interpersonal relations (e.g., the stability of our family relationships), or interactions with things we come across in our environment (e.g., losing your temper with a computer that refuses to do what you want).

Negative Emotional Responses and User Behavior

For the most part, we are unable to control the factors impacting on emotional states experienced as a result of our interpersonal relations (e.g., arguments, the dissolution of relationships, and family problems). In contrast, we largely get to choose which things we interact with in our environment, how often we do so, when we use them, and how we choose to do so. This typically means, when the objects in our environment fail us or give rise to some initial, negative emotional state, we promptly walk away from them or seek alternatives. Obviously, this is not always the case, as we are bound by various factors, such as our budget, workplace, general location, and our physical and mental capacity to use the things available to us. However, we have much greater freedom to simply say "This isn't good enough; I am going to look elsewhere!".

The capacity to reject an object or element in our environment for another is, perhaps, a designer's biggest problem. If a product does not meet our requirements, there are usually tens, hundreds, and even thousands of alternatives for us to investigate and choose in its place. This is why it is essential not only to provide a positive emotional experience but to limit the potential for negative emotional experiences, too. The emotions we experience when interacting with products, such as computers, mobile phones, and tablets, might (as a general rule) not be as extreme as those we are capable of experiencing through interpersonal relations, but they can be just as enduring. Think about, for example, the level of devotion to Apple’s products, exhibited by many customers globally.

A Negative Emotional Response Example

We probably all have a story of a product that drove us insane, no matter how long ago it was. For example, I had a dishwasher where there were five washing functions with similar symbols for each. In order to reset the dishwasher after a cycle was complete, you had to hold two of these buttons down together simultaneously. For some reason, this would not always work, and there was a particular knack to resetting it so you could start a new wash. Sometimes I would spend as long as three or four minutes madly pushing at the buttons (with varying degrees of pressure), before I could put the thing on. As you can expect, this was frustrating and ultimately the dishwasher was considered as a last resort when the crockery and cutlery needed to be cleaned. From this point onwards, when buying kitchen appliances, the interface became something of a major consideration.

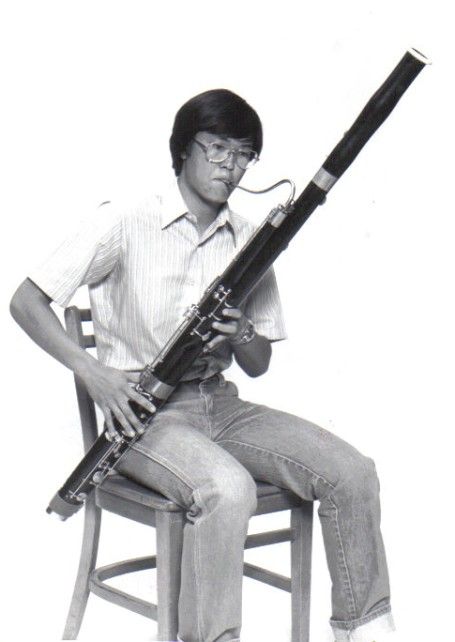

Therefore, while the dishwasher may have been effective at cleaning dishes, cutlery etc. (i.e. its core function), the negative emotions (frustration, anger, disbelief, etc.) induced by the poorly designed user interface meant it would be seen as a bad product. Sometimes we find ourselves putting up with bad products. Why do we do this? Nigel Derrett, a technical consultant who took the time to analyze the bassoon musical instrument as an appliance, derived a law about interfaces called Heckel’s law (after the inventor of the modern bassoon), which says:

“The quality of the user interface of an appliance is relatively unimportant in determining its adoption by users if the perceived value of the appliance is high.” —Heckel’s Law (by N. Derett)

This means that if a product offers a very valuable service that can’t be otherwise obtained, people will put up with it, even if it has a bad interface. Nigel Derrett observed that the value offered to the player by the instrument arises purely from the emotional responses it elicits. The difficulties in the interface of the bassoon were in part dictated by the laws of acoustics and the properties of wood. He noted though that in computer and information appliances the designer is much less constrained by such restrictions, and hence there is no excuse for poor interface design. So, if we want to build products that will be adopted and used, it is not enough to simply develop products that are effective in one key area; they must:

satisfy the core demands, and

provide a positive response or little emotional response at all.

For many products, their success lies in our ability to carry out one or more tasks without even noticing they are there. For example, a clock that shines as brightly as a lighthouse at night would not provide a particularly pleasant experience, but a clock that can be seen in the dark, yet does not shine so bright as to keep us awake at night, probably would. It is within these considerations of who, where, when, and how things are to be used that we learn how to design products that stimulate positive, rather than negative, emotional responses.

Author/Copyright holder: Pearson Scott Foresman, Wikimedia. Copyright terms and licence: : CC0 Public Domain

The bassoon in action. It takes several hundred hours of practice to learn to play a musical instrument through counterintuitive and sometimes painful interfaces. Why do people continue to do it when we can have almost any sound effortlessly reproduced by computers?

Negative emotions are not always a bad thing!

Author/Copyright holder: Katerina Kamprani, Facebook. Copyright terms and licence: Fair use

Cutlery pieces that would drive you insane if you tried to use them! However, they would be a great source of pleasure and laughter if gifted to a friend.

Take a look at the cutlery in the image above; do you see any potential problems? Would we be able to use these tools for their usual purpose? The obvious answer is 'no!'. These pieces of cutlery are, thankfully, not intended as eating tools; they are one of a number of simulated products from 'The Uncomfortable', the brainchild of Athens-based architect Katerina Kamprani. If these items were intended as eating tools, there would be some high levels of frustration and anger. With the hinged tines, the forks are as good as useless, and the combination of a spoon and fork head linked together would serve us little better.

However, the user experience might be awful, but aesthetically, they are appealing, amusing, and many people would probably want them for these exact reasons. Objects and products are judged not only by how they behave but also in terms of their superficial characteristics, which often serve no tangible benefit to the user. Therefore, our focus should be dependent on what the product is for. If it is to help users carry out some important goal, then the user experience is of the utmost importance. In contrast, if objects are purely for the purpose of aesthetic enhancement, such as a wall poster or ornament, the focus should be on the superficial qualities.

The Take Away

In the developed world, we have the benefit of choice; if a product fails to provide us with a positive emotional experience, we can simply look for an alternative. Consumerism is now more cutthroat than ever; no sooner has one product been released, another, similar product appears in its place on the shelf. To ensure survival, businesses and designers must not only develop products that are effective, but they must also enhance positive aspects of the user experience and limit or eliminate negative aspects of the user experience. At the root of both these achievements is an understanding of who the users are, where and when they will use the product, and how the product is going to be used. So, we can conclude, the quality of human-product interactions is influenced significantly by the knowledge designers have of their particular product domain and the intended user base.

References & Where to Learn More

Derrett, N. (2004). Heckel’s law: conclusions from the user interface design of a music appliance—the bassoon. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 8(3-4), 208-212.

Hero Image: Pixabay. Copyright terms and license: CC0 Public Domain